Intel will outpace Moore's Law, CEO Pat Gelsinger says

The chipmaker wants to catch up to competitors in 2024 and surpass them in 2025.

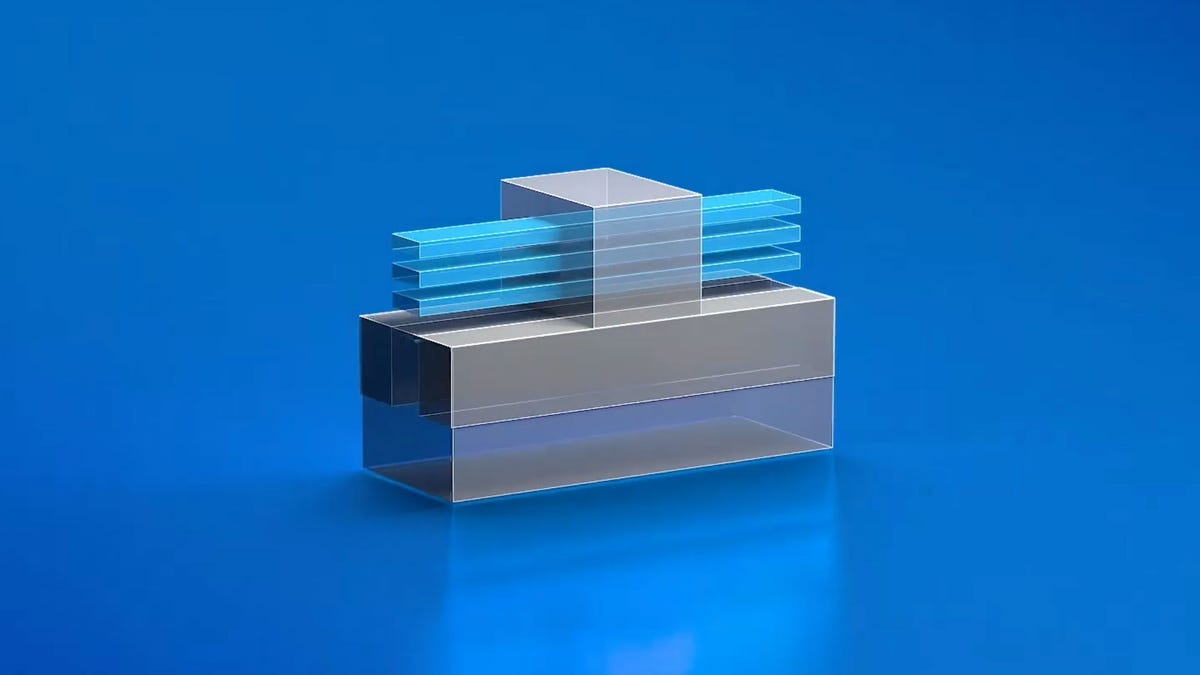

Intel RibbonFET transistors are a key part of the chipmaker's recovery plan.

Moore's Law, the gauge of steady processor progress from Intel co-founder Gordon Moore, has taken a beating in recent years. But with new chipmaking technology, it's making a comeback, Intel Chief Executive Pat Gelsinger said Wednesday.

"Moore's law is alive and well," Gelsinger said at the company's online Innovation event. "Today we are predicting that we will maintain or even go faster than Moore's law for the next decade. ... We as the stewards of Moore's Law will be relentless in our path to innovate."

That's a bold statement from a company that's struggled to advance its chip manufacturing for the last half decade or so and that's lost its leadership to the two other top chipmakers, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. and Samsung. It signals that Intel is willing to fight to reclaim its status and to try to inject new excitement into a lackluster processor business.

Moore's Law, strictly speaking, stems from Moore's observation in 1965 (somewhat updated in 1975) that the number of transistors on a processor doubles every two years. It's not a physical law, but instead a reflection of the economics of miniaturization: By improving manufacturing, more circuitry can be built onto a chip, making it more powerful and funding the next round of innovations.

But miniaturization has faltered as research and manufacturing grow ever more expensive. Chip elements are reaching atomic scales, and power consumption problems limit the clock speeds that keep chip processing steps marching in lockstep.

As a result, people use Moore's Law these days often to refer to progress in performance and power consumption as well as the ability to pack more transistors more densely on a chip.

Gelsinger, though, was referring to the traditional definition referring to the number of transistors on a processor -- albeit a processor that could consist of several slices of silicon built into a single package. "We expect to even bend the curve faster than a doubling every two years," he said.

Moore's Law is alive and well, Intel believes.

Success will mean Intel just catches up to rivals, a moment Gelsinger has pledged will happen in 2024. Intel struggled to move from its 14-nanometer manufacturing process to the 10nm process, while TSMC and Samsung maintained progress better.

Intel's Alder Lake processors now shipping

Intel employed its latest manufacturing process, called Intel 7 and formerly called 10nm Enhanced Superfin, to build its new Alder Lake processor for PCs. It's begun shipping Alder Lake chips, formally called 12th Generation Core processors, to desktop PC makers for use in gaming machines.

The company is shipping desktop processors now and will begin shipping high-performance laptop processors next month, said Gregory Bryant, executive vice president of Intel's Client Computing Group, at the Intel event. That's notable given that for years, Intel used two different manufacturing processes and chip designs for its desktop and mobile processors.

Alder Lake chips, which combine performance processor cores for speed with efficiency cores for better battery life, are Intel's answer to increasingly competitive AMD processors and Apple's new M1 Pro and M1 Max chips in its new MacBook Pro laptops.

Intel RibbonFET and other chip improvements

Along with packaging, Gelsinger pointed to two major developments he expects will help Intel reclaim its leadership. First is RibbonFET, a technology more broadly called gate all around, or GAA. It transforms transistors so that current travels in a stack of thin ribbon-shaped semiconductors completely surrounded by the gate material that switches the current on and off.

Second is Intel's PowerVia, more broadly called backside power delivery. This adds new processing steps to chipmaking but means transistors draw electrical power from one side while connecting to data communication links on the other. Today's chips try to cram both functions into one side, adding complexity and limiting miniaturization.

Also key will be adoption of extreme ultraviolet chipmaking equipment, which uses a smaller wavelength of light to etch transistor circuitry onto silicon wafers. Upgrading is extremely expensive, and TSMC and Samsung beat Intel in the shift to EUV, but the upgrade simplifies manufacturing that otherwise requires more steps.

Intel also has pledged to be first in a later upgrade to high numeric aperture EUV. That's another step on Intel's plan to surpass TSMC and Samsung in 2025 after catching up in 2024.