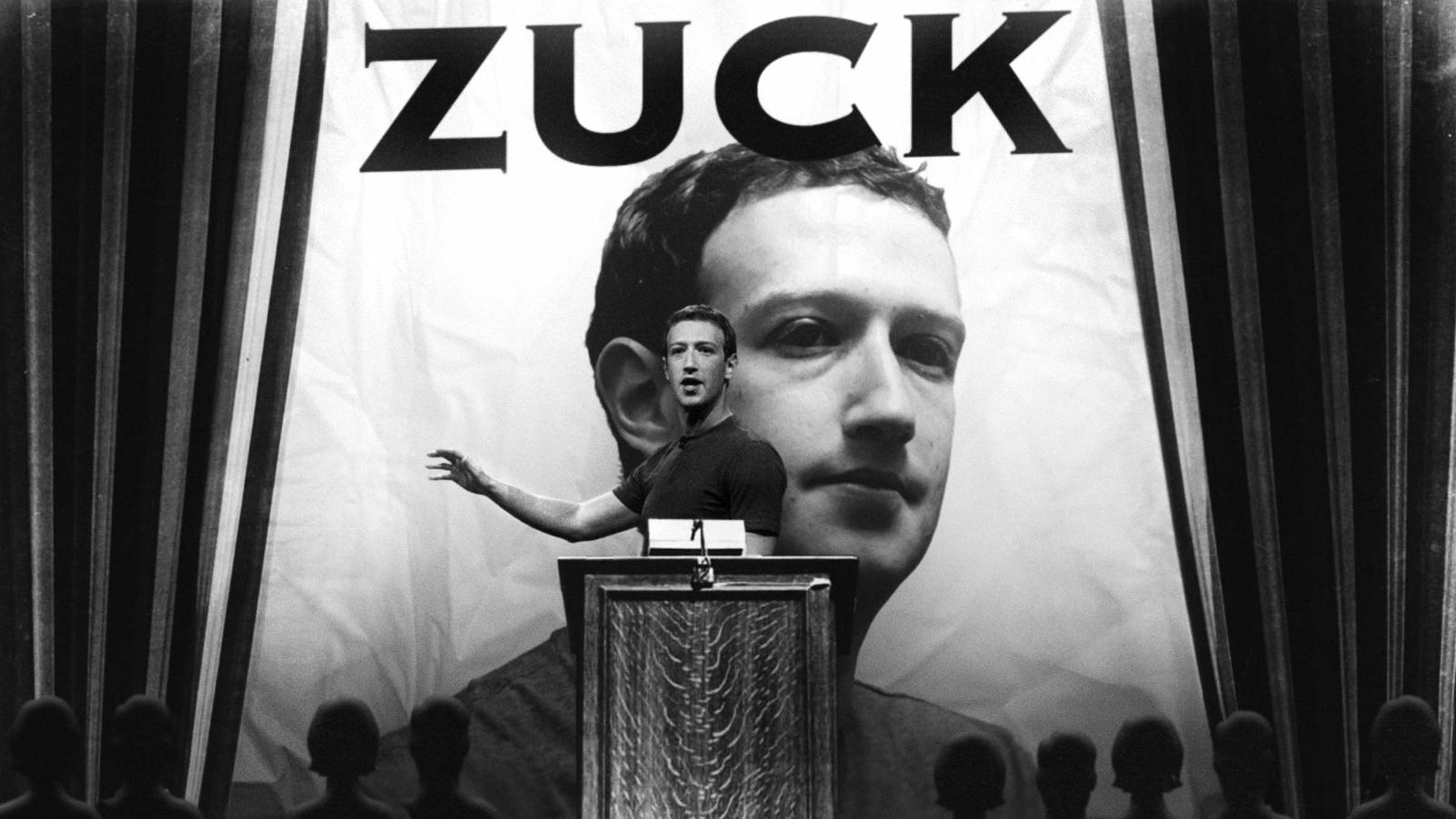

Citizen Zuck: The making of Facebook's Mark Zuckerberg

The world’s largest social network needs fixing. Facebook’s frontman needs to show he can do it -- fast.

"All children are artists. The problem is how to remain an artist once you grow up."

-Pablo Picasso

(Listed on Mark Zuckerberg's Facebook profile under "Favorite Quotes")

There's a story about Mark Zuckerberg visiting his hometown of Dobbs Ferry, New York: A few years ago, he and his wife, Priscilla Chan, allegedly walked into Yuriy's Barber Shop, a four-chair parlor with a blue awning over the doorway and a neon "open" sign buzzing in the window. The shop sits in a brick building at the end of Cedar Street, one of the main drags in town.

Zuckerberg, who grew up in the sleepy town about 25 miles north of New York City, was supposedly visiting from California. Yuriy Katayev, who claims to have been his high school barber, says he was excited to see his old regular. The 50-year-old immigrant from Uzbekistan tells me he asked Dobbs Ferry's most famous son about -- What else? -- Facebook.

"It's OK. People give me shit over it now," Katayev says Zuckerberg told him.

"It's not easy to control now -- because it's too much," Katayev tells me Zuckerberg said. "It's too big."

Great story, but Zuckerberg says it's not true. Three days after telling Zuckerberg's representatives that we'd spoken to his barber, Zuckerberg says he doesn't know Katayev and never visited his barbershop. Katayev, who proudly posed for photos in his shop, swears the visit really happened.

Which shows how much Facebook's chairman and chief executive gets caught up in his own version of fake news.

And fake news was one of the issues that drew Zuckerberg to Capitol Hill last week, where he was grilled by US lawmakers over how he and the world's biggest social network have screwed up. Facebook, Zuckerberg now admits, has become a tool for hate groups who use the platform to harass and intimidate, and for state actors like Russia to manipulate opinion through false news with the aim of interfering with elections, including the 2016 US presidential race.

Dobbs Ferry, New York, barber Yuriy Katayev says Facebook's chief shared his thoughts about the social network. Zuckerberg says it's fake news.

Just in the past month, Facebook has been hammered for the Cambridge Analytica scandal, in which it mishandled users' data by being, in its own words, "naive" about how others could exploit the personal information Facebook collects on its 2.2 billion users. That info is its main currency. Knowing your age, location, likes, interests and other personal data allows it to target lucrative ads on your news feed. It's also why Zuckerberg, 33, is now the fifth richest person in the world, with a net worth of about $71 billion.

"We didn't do enough to prevent these tools from being used for harm," Zuckerberg said as he apologized repeatedly during 10 hours of testimony in two hearings before the Senate and House. "It was my mistake, and I'm sorry. I started Facebook, I run it, and I'm responsible for what happens here."

For better or worse, Facebook and Zuckerberg have become the proxy for all of Big Tech. It's part of the reason lawmakers, already concerned that companies like Facebook, Google and Apple have too much power and influence over our lives and the economy, demanded Zuckerberg testify -- as if answering for the entire industry.

Facebook's mistakes have also raised questions about whether Zuckerberg is a trustworthy custodian of people's data, and whether he's the right person to oversee one of the most powerful information platforms on the planet. Forty-three percent of Facebook users say they're "very concerned" about invasion of privacy, up from 30 percent in 2011, according to a Gallup poll released last week.

Mark Zuckerberg in his high school yearbook.

"While Facebook has certainly grown, I worry it has not matured," said Rep. Greg Walden, chairman of the House Energy and Commerce Committee and a Republican from Oregon. "It is time to ask whether Facebook may have moved too fast and broken too many things."

Zuckerberg, through a spokesman, declined to be interviewed for this story.

Zuckerberg's turn on Capitol Hill marks a dramatic fall from popularity for the CEO. Just last year, he set out on a nationwide tour to learn how people "are living, working and thinking about the future." He released photos of himself doing stuff like helping out at a farm and working on a car assembly line. The trip was one of his annual challenges, basically New Year's resolutions on steroids. Past challenges have included learning Mandarin, building an AI assistant for his home and eating meat only from animals he'd killed. (For 2018, he said on Jan. 4 he was "focusing on fixing" Facebook.)

But as he crisscrossed the country last year, people began to wonder whether he might be preparing to run for elected office -- even president -- someday.

These days, not so much.

Amid all the scrutiny around Zuckerberg, I wanted to see firsthand what people thought of him. So in January, I visited one of the more controversial stops on his trip: Williston, North Dakota, a major hub for the fracking industry in the United States. I wanted to understand the mechanics of how his tour unfolded and to see what the people of Williston learned from him and what he learned from them. Of all the cities on Zuckerberg's tour, Williston may have been the most interesting stop for him, a source close to Zuckerberg said.

I also ended up in the one place he didn't visit on his tour: his hometown. It makes sense he'd skip Dobbs Ferry, since his goal was only to stop by states he'd never visited before. But if we're all products of our environment, it was useful to get a raw, inside glimpse of one of the most powerful people in the world from those who knew him early on: people including his old fencing coach, classmates and neighbors.

Last year, Zuckerberg went on a listening tour to small town America. Clockwise from top left: ranch in Piedmont, South Dakota; candy story in Wilton, Iowa; cattle farm in Blanchardville, Wisconsin; Sunday service at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina.

Well before the 2016 election or the Cambridge Analytica scandal, Facebook's size has been a topic of scrutiny. It's a giant corporation with more than 27,000 employees worldwide and offices around the world, including Silicon Valley, New York, Brazil, London and Thailand. As a social network -- and a vehicle to reach the people of planet Earth -- its reach is unmatched.

But it's not just Facebook's size that's under the microscope. Its very nature is being examined and, with it, its boy wonder co-founder. Zuckerberg will go down as one of the most important American entrepreneurs, ushering us into the digital age like no one before. He tamed the Wild West of the internet by basically giving us all name tags and a place to post baby pictures, political rants and anything else we wanted to share.

As Facebook has grown, so has Zuckerberg's influence. He is essentially his generation's William Randolph Hearst -- an outsize figure with his hand increasingly in the worlds of news and politics. There are some striking similarities: Both men dropped out of Harvard, made their fortunes in the San Francisco Bay Area and had acclaimed movies made about them.

Both popularized clickbait, though in Hearst's day it was called yellow journalism. Both men have their fingerprints on wildly consequential global affairs: Hearst bragged about starting the Spanish American War, while Zuckerberg, to his dismay, saw his platform twisted into a propaganda tool during the 2016 US presidential election.

But while Hearst was a proud media tycoon, Zuckerberg has only recently come to acknowledge that he's responsible for the content posted on Facebook. Zuckerberg maintains that Facebook is a technology company and a social networking platform -- not a media company. It's perhaps one reason Facebook is trying to loosen its grip on news -- tweaking its news feed algorithms this year to focus more on personal posts than news stories.

Zuckerberg testified for two days before Congress about Facebook's data privacy.

That effort may be moot, since Facebook is still one of the most powerful content aggregators and news distributors in the world. About two-thirds of Americans use Facebook, and a majority of those get news on the social network, according to the Pew Research Center.

Citizen Zuck doesn't need to be our president. In some ways, he's more powerful. So who is he?

Zuckerberg grew up in a white house with gray-trimmed shutters, on a quiet street corner on the east side of Dobbs Ferry. The terraced lawn is lined with rocks and small bushes. A brick stairway leads to the front door, and a gray stone walkway spirals over to the side of the house, where there's an entrance to a dental office. Out front, a wooden park bench with a sign hanging next to it greets patients: E. Zuckerberg, D.D.S. DENTIST.

The "E" stands for Edward, Mark's dad, known around town as "Painless Dr. Z." He's a dentist from Brooklyn who married Karen Kempner, a psychiatrist from Queens. They moved to Dobbs Ferry in 1980. Four years later, on May 14, Mark Elliot Zuckerberg was born.

Dobbs Ferry, a town of about 11,000 people, is a postcard for upper middle class suburbia. It's about 80 percent white. From the train station on the Hudson, which shuttles most of its professional class down the river to Grand Central Terminal, fog rolls off the water and you can see the Manhattan skyline in the distance. The town has tree-lined streets and storybook architecture. There's no litter or graffiti in sight, though the stop sign on the corner of Zuck's old house has a sticker on it that says "resist," which may give you a hint as to the leanings of the town (or at least parts of it).

Zuckerberg, co-captain of the men's fencing team, poses with the 2000 Ardsley High women's fencing team.

Everyone in Dobbs Ferry knows Zuckerberg grew up here -- his name rings around town like Prince's does in Minneapolis, or Lebron's in Akron.

"It was a great environment to grow up in," says Dobbs Ferry Mayor Bob McLoughlin. His son played youth soccer with Zuckerberg and his daughter often served him when she worked at the pizzeria on Main Street. "If you have two great parents like he did, you had a head start in life."

All the locals seem to have a story of the Zuckerbergs. At Pride Cleaners, a nearby dry cleaner, the owner Chong Park remembers Mark coming in as a young boy with his mom. Park's mom, Sang Kyu, worked the register and Mark would ask her, "Nana, could I have a lollipop?" Sang Kyu, who spoke Korean and not much English, would give him a Dum Dum.

The Zuckerbergs don't live here anymore. Edward ran his dental practice from the side of the house until a few years ago, even after Facebook's IPO made him extremely wealthy. Not dentist rich, Silicon Valley rich. Mark's parents sold the 2,500-square-foot house for $900,000 in 2013, according to property records, and moved to California. His father now runs a consultancy called Painless Social Media.

Before his parents moved to California, though, Zuckerberg apparently considered putting down his own roots in the area. The rumor is that five or six years ago, Zuckerberg was looking at multiple properties in neighboring Hastings, south of Dobbs Ferry, to build a massive estate. It's a piece of town gossip, but one that was repeated to me by several locals, including the mayor. He never bought the properties. Instead, they were snapped up by billionaire hedge fund founder David Shaw.

The house where Zuckerberg grew up still has his father's dental practice sign out front, even though the family has moved to California.

I ask Mayor McLaughlin if Dobbs Ferry plans on honoring their local boy done good, with a parade or a street name or something.

"Zuckerberg Way…" he replies. "Hey, that's not a bad idea."

Amid the clanks and clashes of swords in the Ardsley High School cafeteria, Diane Reckling shows me her favorite picture of her prized pupil. It's a photo of the 2000 Ardsley High women's fencing team, and a baby-faced 15-year-old boy with a wide smile is in the center of the group shot.

The framed photo usually hangs in Reckling's office, but the 75-year-old coach took it down -- the first time she's let any reporter see it -- to show me how she remembers Zuckerberg: smart, skilled, but kind of silly. Behind her, students on the fencing team line up in two opposing lines, running through drills.

"He was a leader. Kids liked him," she says of Zuckerberg, who was co-captain of the men's fencing team. "He was a ham, but he also commanded a lot of respect."

Her daughter Kathleen, sitting next to her, chimes in. She was a year behind Zuckerberg in school -- a freshman when he was a sophomore -- and his fencing teammate. She went on to fence at Columbia University, then internationally. Now she's the assistant fencing coach at Ardsley. "The legend of Mark Zuckerberg is of being someone who is very removed, which is not the kid we knew," she says.

They delve into their memories of Zuck.

Diane recalls picking him up from his parents' house on Saturdays and taking him to fencing tournaments. Zuckerberg attended Ardsley High -- a short drive from his house across the Saw Mill River -- for his freshman and sophomore years before transferring to Phillips Exeter Academy, a private boarding school in New Hampshire. Diane says she was sad to see such a talented fencer go and tried to persuade his parents to keep him at Ardsley. She and her daughter both remember his skill in matches.

"He's really quick," says Kathleen.

"Very quick," his old coach stresses.

"When he had gone to Exeter, he eventually switched to saber, which is not a weapon that we offer here," says Kathleen. "And that's very lightning fast -- like the quickest of all of them, in terms of having to make a decision."

As she says this, she taps her hand on her leg rhythmically, as if to conjure up the image of a fighter making moves and countermoves: bam, bam, bam, bam.

So, move fast and break things.

That was Facebook's motto for the first decade of its existence. If you're not making mistakes, you're not moving fast enough, Zuckerberg said. That approach drove the company's meteoric rise, but it also got Facebook into trouble. When the social network introduced its news feed, privacy advocates cried foul over people's info being shared so freely. Publishers freaked out every time an algorithm tweak spurred a dip in their traffic.

"It's not surprising that the creator of Facebook was a fencer," Kathleen says.

For Facebook, it's become an endless cycle of reacting, absorbing blows, parrying and -- for the sake of all of us -- hopefully solving the world's growing privacy concerns.

Zuckerberg's high school fencing coach Diane Reckling (right) and her daughter Kathleen.

Kathleen recalls Zuckerberg leading singalongs of "Revolution" by the Beatles during fencing road trips. She says his AOL Instant Messenger screen name was Themarke51, which confirms reports from 2013 that Zuckerberg's old Angelfire webpage had surfaced online. On the page, which has since been taken down, a 15-year-old Zuck calls himself "Slim Shady" and proclaims his love for quesadillas. He also runs an experiment on the page in which he tries to link friends on the web and map out their connections. (Sound familiar?) One of the names on the map is "Kathleen R."

It's rare to hear someone talk about Zuckerberg like she does, reminiscing about lots of normal kid stuff: She talks about him baking brownies for a fencing fundraiser with a teammate named Julia. About him hanging out with his friend Pete. And how he accidentally poked a girl in the eye with his fencing foil.

A few hallways down from the cafeteria where the fencers practice, a motivational poster of Sheryl Sandberg -- Facebook's chief operating officer and Zuckerberg's right hand -- hangs on the wall in the computer lab. Rudy Arietta, Ardsley High's principal, tells me that two years ago, a computer science student wrote a letter to Zuckerberg asking him to speak at graduation, but he never heard back.

Even after traveling the country all of last year, Zuckerberg hasn't been back to Ardsley or Dobbs Ferry for a formal visit as the CEO of Facebook. At the hearing with the House last week, Rep. Eliot Engel, a Democrat from New York, beckoned Zuckerberg to come back home. "I hope that you might commit to returning to Westchester County, perhaps to do a forum," he said. "I know that Ardsley High School's very proud of you."

There are vast, open plains dotted every few miles by giant gas flares just outside Watford City, North Dakota. The 20-foot stacks tower over gravel fields where oil is pumped, huffing giant balls of fire into the sky. The flames make the atmosphere directly above look hazy. Up close, the machinery is deafeningly loud but from a distance, the mass of fire and swirls in the sky look almost celestial, like something out of Van Gogh's "The Starry Night."

Gas flares just outside Watford City, North Dakota.

The flares are burning off gas in the Bakken, a rock formation that stretches 200,000 square miles beneath parts of North Dakota and Montana. It's a nerve center of the US fracking industry, in which rocks are fractured to extract oil. In July, Zuckerberg and his team visited to learn more about the practice and the people -- mostly men -- behind it.

"I believe stopping climate change is one of the most important challenges of our generation," Zuckerberg wrote on his Facebook page after the trip. "Given that, I think it's even more important to learn about our energy industry, even if it's controversial."

Zuckerberg's post was accompanied by a professional photo of himself on an oil rig. In the picture, it's about 80 degrees and sunny. Zuck is wearing a blue jumpsuit and white hard hat (though not his safety goggles, a detail a few safety inspectors later bemoaned). He's flanked by six male rig workers.

From 2009 to 2015, while fracking operations were at their peak, the Williston-Watford area was a boom town. Thousands of men flocked there for oil jobs, many making $100,000 a year with only a high school diploma. The towns expanded to accommodate the workers with new housing, restaurants, schools, gyms, bars and strip clubs. But the price of oil began to slide in 2014, and the cities had to reckon with the downturn that followed.

Even with the influx of new residents, Williston and Watford are both more than 80 percent white. In the 2016 election, Williams and McKenzie counties, which house Williston and Watford, respectively, went to Donald Trump with 80 percent of the vote.

Downtown Williston, North Dakota.

As with most of the other stops on Zuckerberg's tour, the visit to Williston, an hour north of Watford, was big local news. But unlike many of Zuckerberg's dispatches from the trip -- like from a Ford factory in Dearborn, Michigan, the "World's Largest Truckstop" in Walcott, Iowa, or a family farm in Blanchardville, Wisconsin -- his post about Williston stirred debate because some locals weren't pleased by how he represented them. In his post, he called out the ratio of 10 men to every one women in town, and the uptick in crime the gender imbalance has caused.

Shawn Wenko, executive director of economic development in Williston, met with Zuck while he was in town and disputes that figure. He says it's closer to five men to every four women. (By walking around town and talking to locals, you get the impression the ratio is more even than lopsided.)

Ronn Ness, president of the North Dakota Petroleum Council, who coordinated Zuck's tour of the oil rig, was taken aback by the post, but was diplomatic in describing how he felt about it: "I probably liked it better my second or third time reading it, to be honest," he tells me.

The reactions show just how much influence Zuckerberg wields and how his mere presence can shake up entire towns. For Zuck, Williston was one stop on his tour. But for its residents, it was a major affair. "It's like planning for a visit from a head of state," says Kira Stenehjem, an ice skating instructor and event coordinator who planned a roundtable dinner Zuckerberg held with town locals. Stenehjem's family founded the First International Bank in Watford and Williston.

I visited Williston and Watford in January, six months after Zuckerberg spent about six hours in town to dredge up goodwill for Facebook. To some of the oil rig workers, his visit was just a "publicity stunt" from an out-of-touch billionaire.

At the Little Missouri Inn and Suites in Watford, about 30 men are taking a safety training session put on by the Hess Corp., a petroleum refineries company. It's an icy day. During class break, the men mill around the small hotel lobby, chatting and drinking the free coffee. Three of them stand in a cluster, and I ask them about Zuckerberg.

Zuckerberg met with oil rig workers in Williston, North Dakota.

"That guy needs to calm down," says one in his mid-20s. He's tall with short dirty blond hair and bed head, wearing a loose-fitting gray sweatshirt. Every oil worker I spoke with would only talk to me under the condition of anonymity because many of the oil companies explicitly forbid them from talking to the press. "He's an asshole," the twentysomething continues.

Another worker, wearing glasses and a black beanie with a bill on the front, chimes in. "[Zuckerberg] hates everyone under him," he says. "Out here, everyone is equal."

The man is talking about all the guys working on oil rigs. Then his complaint gets more specific. "He went on a rig in tennis shoes!" he adds, getting animated. "Just because he has money." (To be fair, there are pictures of Zuckerberg walking around the site and office trailer in his standard gray Nike Flyknits. But in photos where he's in full jumpsuit gear, he is wearing dark brown, heavy-duty work boots.)

Some were more forgiving. One man in his 40s appreciated Zuckerberg taking the time to learn about the industry, even if the two sides didn't agree. "It's important that we hear each other," he says.

Mark Zuckerberg is intensely private. That might come as a shock considering Facebook is designed to let people post their entire lives online. It might be even more surprising considering the Facebooker-in-chief tries to lead by example: In the past few years, Zuckerberg has shared snippets of his life's most intimate moments on his Facebook page, like his daughter Max's first steps, or a post opening up about the struggles he and his wife went through to conceive after three miscarriages.

But those revelations -- as honest and inspiring as some are -- are approved and authorized by Facebook's vast PR machine. Everything you see from Zuckerberg, you were meant to see. Everything else is off limits. So, Zuckerberg's Facebook page gives you a window into his life, but that window is glossy and windexed. (He declined to give the name of his Washington, DC, hotel last week when asked by Sen. Dick Durbin -- even though Facebook encourages you to "check in" where you are.)

When he travels, he takes a professional photographer. (There have been stories about how he makes himself look taller than his 5-foot, 7-inches.) While he was on his US tour, I learned that he employed an "advance" team, a tactic typically used by politicians. It's a coterie of aides who fly ahead to a location where a candidate -- or in this case, Zuckerberg -- will make a public appearance, to set up accommodations and make sure the optics are just right.

Including security, these can be large-scale operations. Last week, Facebook said in an SEC filing that the company spent more than $7.3 million on Zuckerberg's personal security in 2017, up almost 50 percent from the year before. The company also spent more than $1.5 million on private plane costs, up from $870,000 in 2016.

One of the leaders of the operation was Ryan Wallace, a program manager for Facebook's "Office of the CEO," according to his LinkedIn profile. He's British and a veteran of the Royal Navy. During his work with the military, from 2007 to 2014, he rose to head of engineering and technology, working with satellites and sensors and setting up the internet in remote locales.

So when Zuckerberg decided to crisscross the country to learn about small-town America, Wallace was one of the people he tapped. Facebook wouldn't make him available for an interview.

It was Wallace who helped orchestrate the trip to Williston. The team first reached out to the office of Mayor Howard Klug to plan the visit. Zuckerberg's aides were at first coy about who the guest of honor would be, saying only it would be an executive from a Fortune 100 company. But while the team asked the mayor's office for help getting the ball rolling, Facebook had one big restriction: No public officials would take part in the visit.

Zuckerberg stopped by Williston, North Dakota, to learn more about the fracking industry.

The trip started with a tour of an oil rig, organized by Ness.

Zuckerberg met with a few people on the oil rig sites, then held a closed-door meeting with rig workers. Ness says Zuck was particularly struck by the fact that many of the men on the rig were his age, in their early 30s. He also had questions about the Dakota Access Pipeline, the controversial underground oil pipe that runs from North Dakota to Illinois, through the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation. He wanted to know everything about the pipeline, but wouldn't reveal his personal feelings, Ness says.

Zuckerberg's aides told Ness the CEO probably wouldn't want to go on a rig and put on the safety equipment. They were wrong. "That's where all the action is," Zuckerberg told Ness.

After the rig visit, Zuckerberg and his team had a roundtable dinner with local residents at Outlaws Bar and Grill in Williston, a restaurant the Stenehjem family owns. The place has rustic decor. A bison head hangs in the lobby. A rifle, animal skulls and pictures of cowboys are on display.

The group -- including Stenehjem's parents, Steve and Gretchen; Wenko, Williston's head of economic development; a school superintendent; an oil and gas industry publicist; a priest and a realtor -- ate in a private backroom with a long table, Zuckerberg in the center. The guests said one member of his team sat in a corner taking notes on a laptop, while the others took up booths outside the private room.

Zuckerberg talked about his annual challenge, followed by free-flowing discussion. Publicist Lynn Welker asked Zuckerberg how he keeps his edge since he has little time to himself. Zuckerberg mentioned the importance of exercise because he has hip issues. He talked about a hunting trip where he killed a buffalo as part of another annual challenge. After he made the kill, he realized, "That's a lot of meat."

And he opened up about his frustrations with the media. "I'll have a meeting, and then I'll read about it in the press the next day. And I'll be like, 'That's not right at all!" he said, according to Fr. Brian Gross. (Author's note: If you're reading this, Zuck, the irony of this isn't lost on me.)

Activists set up 100 lifesize cardboard cutouts of Zuckerberg on the Capitol lawn last week.

The dinner was supposed to last an hour, but went on for two and a half. As the night wore on, people at the restaurant figured out Zuckerberg was in the building. About 15 to 20 people wanting selfies began to line up at the entrance of the backroom, Welker says.

The line would have been longer if it weren't for, well, misinformation on Facebook. Word of Zuckerberg's appearance eventually found its way on to "New Williston Connections," a popular Facebook page with 24,000 members. Someone wrongly posted that Zuckerberg was at Lucy Lu's, a local steakhouse. Rosie Durbin who works at Home of Economy, a regional superstore for work boots and other rig supplies, told me she hopped in a car with her friends and headed to Lucy Lu's, but came up empty.

After dinner, Zuckerberg took as many pictures as he could before his team whisked him away. The Zuckerberg tour had to march on.

On the last stop of his trip, in Lawrence, Kansas, Zuckerberg explained his motivations for the tour during a Q&A session at the University of Kansas.

"One of the things that struck me was that running Facebook, which is such a global company, I'm more likely to end up traveling to a capital city in another country than to a lot of places in our country," Zuckerberg said. "I wanted to get out and learn and hear from folks, and just be able to see how people were thinking about their work and their lives, and thinking about the future, and the opportunities, and what they were worried about."

Taking him at his word, the tour was a valiant endeavor. But even after all the time, money and jet fuel spent, there still seems to be an overarching distrust of Facebook and Zuckerberg.

In Williston, I talked to groups of college and graduate students who don't trust Facebook to be the keepers of their personal data. Two women say the site gives them FOMO when they see their friends having fun without them. Others bought into conspiracy theories about Facebook and Instagram, which Facebook owns, using your phone's microphone to spy on you for ad targeting.

"I could have a dream about buying a shirt, and it will show up on Facebook," says Carmen Carter, a 26-year-old nursing student. (That theory came up twice during Zuckerberg's congressional hearings, and he denied it.)

It's the same story back in Dobbs Ferry. When you ask people about Zuckerberg, they'll go in one of two directions: They'll either talk about some personal connection, like knowing someone who went to his dad's dental office. Or they'll use the question as an opportunity to rail against Facebook.

"His invention is destroying the culture," says one bartender, who asked not to be named because he didn't want to publicly insult the hometown boy. "It's cheapened relationships."

A few doors down from Yuriy's Barber Shop, there's a trendy pizza place called The Parlor. Inside, it's meant to look hip and industrial, with exposed beams and a mural painted on a metal wall. The room looks like it belongs in Facebook's famed Frank Gehry-designed headquarters in Menlo Park, California, which has the same decor sensibilities. On the metal wall, a sign spray painted in bold white capital letters reads:

"I LIKE THE REAL YOU BETTER THAN THE INSTAGRAM YOU."

Now that Zuckerberg has been forced into the spotlight in a way he never expected, Facebook's future depends on the world liking the real him, too. ●

Correction, April 20, 10:17 a.m. PT: The original version of this story quotes Yuriy Katayev's recollection of a conversation with Zuckerberg. Zuckerberg says he never spoke with Katayev.