Universal Music toasts BigChampagne

Instead of turning to Nielsen's SoundScan exclusively to track music consumption online, the top recording company signs long-term deal with BigChampagne.

Count BigChampagne among the companies trying to cut into Nielsen's media-measuring empire.

Universal Music Group, the largest of the four major recording companies, has agreed to a multi-year deal that calls for BigChampagne to help track the popularity of the label's music online. Traditionally, Universal has relied on Nielsen's SoundScan for such chores.

BigChampagne tracks online music and video consumption. Headquartered in Beverly Hills, Calif., BigChampagne is perhaps best known for being the first of the business-intelligence companies to measure activity at file-sharing networks, such as the original Napster.

"With the addition of BigChampagne, we provide a comprehensive view of the marketplace," Jim Urie, president and CEO of Universal Music Group Distribution, said in a statement. Urie said that the ability to measure radio, the Web, and brick-and-mortar retail stores "results in more opportunities for our artists and labels."

Universal's embrace of a Web intelligence product is symbolic of how important the Internet has become to the traditional music business, and the latest example of how Nielsen's competitors in a number of entertainment sectors are moving in on its core business.

On Saturday, Kenneth Li of The Financial Times reported that NBC Universal, Time Warner, CBS (parent company of CNET News), and Walt Disney are part of a consortium that intends to challenge Nielsen's decades-long control over the measuring of U.S. television viewership.

Nielsen representatives did not respond to an interview request but were quoted in Tvbythenumbers.com. They said the company "is committed to measuring across all screens--known in the industry as 'three screens': television, computer and mobile--as part of our long-term strategy. Over the last three years, we've invested more than a billion dollars in research and development as part of this effort."

Without accurate tracking numbers, advertisers say they risk wasting some of the $70 billion they spend on the U.S. TV industry annually. The perception by some in a multiple media areas is that Nielsen isn't equipped to provide all the answers--especially when it comes to the Web.

"The most deficient thing is there's no single source measurement (for TV and digital video)," Sam Armando, senior vice-president of audience analysis at Starcom Mediavest, told the Times.

Some in the music industry say a similar void exists in that sector. BigChampagne, which reached profitability not long after launching in 2000, hopes to fill it.

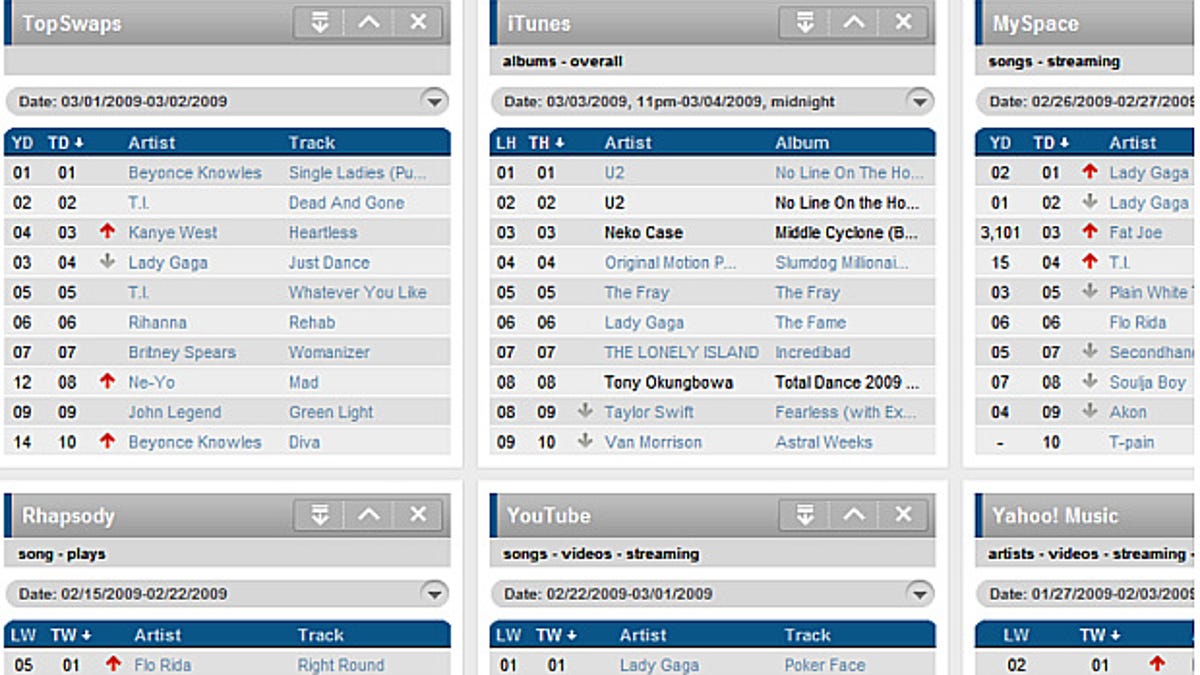

Last week, the company rolled out BC Dash, a new browser-based tracking system that allows a user to monitor in real-time song sales or streams at a host of Web sites, offline locations and peer-to-peer networks. Some of the sources include iTunes, YouTube, MySpace, retail brick-and-mortar record stores, and Limewire.

The data can help the music director at a regional radio station learn what tunes are hot and that information can help him or her decide what songs to play.

BigChampagne CEO Eric Garland is the first to admit that the company has benefited from the massive shift in listener's habits the past several years. Ten years ago, Garland said, his company was surrounded by doubters, people who didn't think there would ever be anyone willing to spend to acquire intelligence about Internet-music listeners. Nine years ago when BigChampagne was founded, the market was insignificant. Not anymore.

"The Internet has inherited the music business," Garland said. "When you look at MySpace plays, Rhapsody, iTunes, Last.fm, all of that dwarfs traditional music purchasing. Instead of CDs, we paid attention to this sleepy little Internet thing, but it happened when no one was watching. Well, we were watching."

To be sure, SoundScan offers customers its own Internet tools and the company has been the nearly unchallenged leader in counting music purchases in the United States since 1992. Anytime a song or album moved up the Billboard charts, it was SoundScan that said it was so. Before SoundScan arrived on the scene, music companies gathered sales information calling stores and asking clerks which records were moving. Not surprisingly, the system was easy to manipulate.

SoundScan changed all that when it brought in bar codes and computers to objective sales tracking.

In a 1992 story in The New York Times, a source told the newspaper that the major record labels likely paid SoundScan $750,000 a year for the company's data.

Things have changed in the 17 years since. Music industry sources say that SoundScan charges the top recording companies "on a market-share basis." That means the larger the share of overall music sales a label possesses, the more it must pay SoundScan for its data. Exact figures weren't available but Universal was paying between $7 million and $8 million a year in the middle part of this decade, the sources said. The third largest label, Warner Music Group, was paying about $4 million.

SoundScan will likely be forced to lower prices as the importance of tracking CD sales decreases--the bread and butter of its business--and Internet sales go up. The company's prices will also be under pressure from smaller but less expensive competitors, such as BigChampagne.

"Given the current economic conditions, every business is trying to do more with less," Garland said. "We have to help them find efficiences because the industry is constricting."