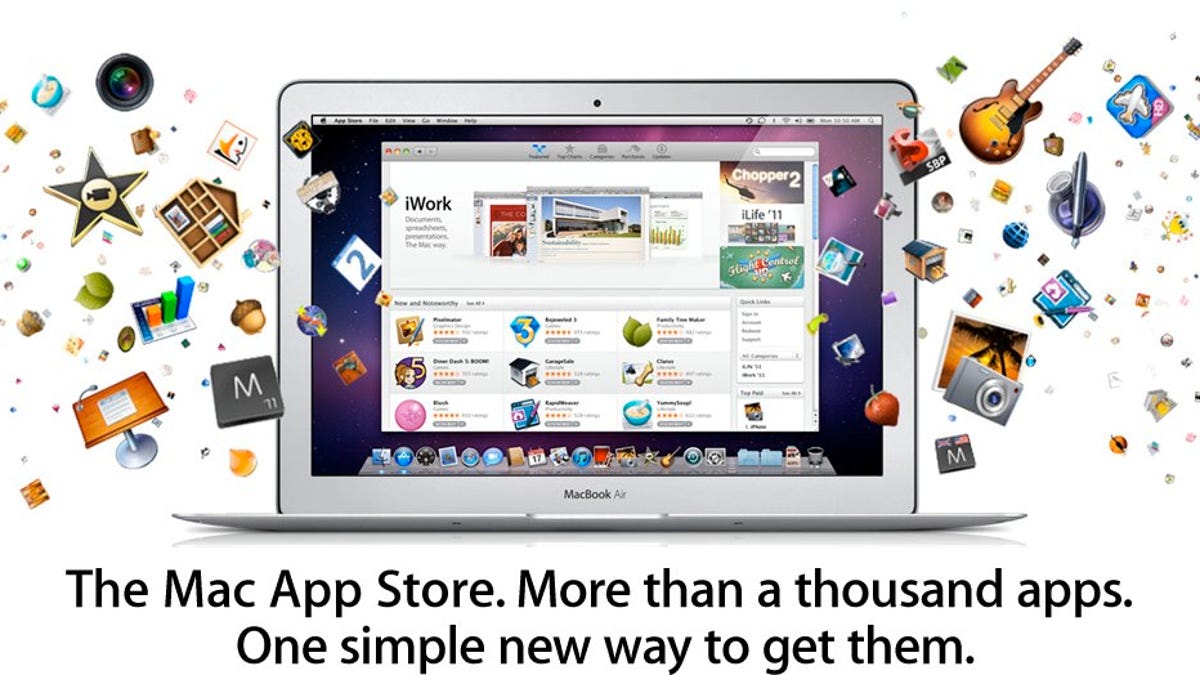

Piracy possibility emerges with Mac App Store

A hack lets some software originally from the Mac App Store run even if it wasn't purchased--but the problem seems to be more with the software than the store.

A weakness in copy protection--the antipiracy mechanism at the heart of many a digital distribution system--has reared its head with Apple's brand-new Mac App Store.

The store, launched yesterday, includes digital rights management (DRM) technology designed to ensure that only a program's purchaser is authorized to run the program. But a hack distributed online apparently can be used to get around the system in some situations.

Although several have reported successful use of the hack to circumvent copy protection, it stems from problems in how software developers get their applications to verify permission to run, not from an irreparable problem with the Mac App Store's DRM.

Nevertheless, the issue spotlights the painful realities of DRM. When it's used, hackers often find a way around it, as happened for example with Blu-ray and DVD encryption. But commercial content creators naturally are averse to seeing their digital products spreading willy-nilly for free, and Apple's removal of DRM from music in iTunes in 2009 and Amazon's option to lend Kindle books are the exception rather than the rule. Just this week, a group of entertainment industry powers unveiled a new DRM and copy-protection technology called UltraViolet.

Apple didn't immediately respond to a request for comment.

But Big Bucket Software's Matt Comi, developer of a game called The Incident that's vulnerable to the hack, said he'll be releasing a new version of his software.

"Too bad they didn't release a Mac App Store beta to developers--maybe we would've noticed this," Comi said. Despite the problem, he added, "First day's sales came in a few hours ago and we're very pleased."

With the Mac App Store hack, a person copies three files--digital receipts--from a freely downloaded application such as Twitter to another app such as Angry Birds that otherwise would have to be purchased before it runs. That second app essentially uses the free app's authorization. Of course, a bootleg copy of the second app must first be obtained, but that's rarely proved an obstacle in for those evading copy protection technology.

News of the hack spread quickly yesterday--but shortly afterward came more news that apparently at least part of the problem lies with the software developer and Apple's suggested verification procedures rather than with a terminal problem with the technology.

"For apps that follow Apple's advice on validating App Store receipts, this simple technique will not work. But, alas, it appears that many apps don't perform any validation whatsoever, or do so incorrectly, like Angry Birds," Apple watcher John Gruber said.

But another observer, Sean Christmann, also laid some blame on Apple. Although Angry Birds developers followed only two of the five steps Apple recommends for verifying the software is authorized to run, Apple's instructions are flawed, Christmann said in a blog post.

Specifically, he said Apple recommends a verification process that checks a text file separate from the application's binary file--in other words, an ancillary file, not the file the computer actually runs. He recommended a validation procedure that uses the application itself.

"At the end of the day, if your app is popular enough it's going to end up on a pirated site, but for the time being, by following the instructions above, you can avoid having your app easily cracked with TextEdit," Christmann said.

Comi had this description of the matter: "The issue relates to comparing bits of data from one file (the Info.plist, in other words, the app's metadata) to bits of data in another file (the receipt). As long as those files are consistent, the app will launch. Pretty obvious in retrospect but easy to overlook. The fix is to not refer to the Info.plist."

Asked if it plans a new version of Angry Birds, Rovio Mobile said, "We'll look into it."

Chester Wisniewski of security company Sophos also cautioned about a side effect of the problem: people might look for pirated software instead of going through the App Store. "Be cautious where you get things," he said in a video. "Don't pirate software. It's the best way to get trojans onto your system."

The Angry Birds application is a good example. "Unfortunately, Rovio did not follow the best practice guidelines that Apple set forth on what to do to prevent this application from being pirated," Wisniewski said. "It's quite easy to imagine it's going to be widely distributed."

Updated 8:56 a.m. PT and 9:18 a.m PT with comment from Big Bucket Software and Sophos.