When it Comes to Human Extinction, We Could Be Our Worst Enemy and Best Hope

Human extinction? It could happen, but it doesn't have to.

There are days when it's hard not to wonder just how much time is left on the clock for humanity.

Whether it's war, famine, another grim report about climate change or a pandemic that's killed 6 million people to date, life on this planet can start to feel precarious. Sometimes, it all feels like an action movie entering its final act.

But is it actually possible that nearly 8 billion humans could one day disappear? That the planet could continue to spin in peace without us?

"The end of the world is such a great concept for giving shape to history," says Anders Sandberg, senior research fellow with the Future of Humanity Institute at the University of Oxford. "We want to know how it ends. We want there to be a meaning or a tragedy or a comedy. Maybe a laugh track at the end of the universe."

It turns out, scientists, scholars, policy experts and more are studying this question, trying to decipher how humanity's end could come about, and whether there's anything that can be done to prevent it.

Well, that's a grim thought

The fact that anyone at all is worried that humans could go extinct is relatively new, says Thomas Moynihan, author of the book X-Risk: How Humanity Discovered Its Own Extinction.

There were fringe whispers in the 1700s. In the 1800s the Romantic poets picked up the idea. Mary Shelley's The Last Man was about a plague that just about killed off humanity. Few at the time were keen to read such an uplifting tale. The rise of Darwinism gave people some understanding that humans were part of a long-running chain of organisms. In 1924, Winston Churchill wrote the essay Shall We All Commit Suicide? about war's potential to destroy humans. But according to Moynihan, perhaps it wasn't until the detonation of the atomic bomb during World War II that people fully realized they might wipe themselves out.

Humans also eventually came to the realization that we might be the only ones out there exactly like us. Whatever we have, however flawed it is, could one day be lost entirely, not just from the planet, but from the universe.

"Once a species is gone, it's gone forever. Extinction is forever," Moynihan says, "We now understand the consequences of that."

There's more we can learn about where we're going as a species by looking into the past (even beyond all the pre-modern humans that are no longer with us), specifically, at the fossil record. In a 2020 article about human extinction in The Conversation, paleontologist Nick Longrich pointed out that 99.9% of all species that have ever lived on Earth are now extinct.

So, maybe our odds aren't great. Further, humans also have some key vulnerabilities that could make it hard to survive some large-scale catastrophe -- we're these large, warm blooded animals that need a lot of food; our generations are relatively long, and we're not the most prolific of breeders, Longrich writes.

Being human also has some advantages, though.

"We're a deeply strange species -- widespread, abundant, supremely adaptable -- which all suggest we'll stick around for a while," Longrich writes, noting that humans are just about everywhere. We can adapt our diets in ways other species can't, and we can learn, and change our behaviors.

Risky business

Those who work in the field of existential risk are nudging people in the present day to do just that: learn from and change our behaviors.

The Future of Life Institute is a Boston-based outreach organization that focuses on how to avoid making big, species-ending mistakes with technology. FLI's advisory board is packed with plenty of names from institutions like the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Harvard University, and Cambridge University, plus Elon Musk, Morgan Freeman and Alan Alda, for good measure.

Over the phone, Senior Advisor for Government Affairs Jared Brown tells me about something called the Collingridge Dilemma. When a new technology is developed, we see the benefits. Fire, for example, was great at keeping us warm and keeping predators away. By the time a technology becomes ingrained in the way a society functions, we start to learn about the downsides -- like burning down villages. Or, you know, three square miles of Chicago in 1871. On the whole, though, we mostly take the good and the bad together. A lot of people die in car wrecks every year, but we still drive cars.

Some lessons you don't get to learn twice.

"That works up until the point where some of the dangers are potentially catastrophic or existential. And you don't get to learn a lesson twice," Brown says.

When FLI looks at its four main existential threats -- artificial intelligence, climate change, nuclear weapons and biotechnology -- tech sits at the core of all of those, even going back to the invention of the combustion engine.

That's why groups like FLI are trying to get the powers that be, like lawmakers, to build safeguards now before we need them.

It's not always easy to talk to people about a subject that's somehow big and scary but also abstract enough not to be an immediate concern. Could a rogue AI intended to maximize paper clip production one day decide that humans are slowing down the process and must be eliminated? Eh, maybe. But it's not going to happen next week.

"The natural instinct is, 'That's somebody else's problem'... [or] even, 'If I believe you, what the heck am I going to do about it?'" Brown says.

In an unsettling turn, the pandemic has brought a bit of recency bias into the equation, he says. Perhaps it feels less like alarmist hand-wringing to worry about an event that seemingly came out of nowhere and affected every person on the planet.

For FLI, the point isn't so much about watching a countdown to disaster.

He said they don't need to know the exact likelihood that something could happen in the next 30 years to know there's enough uncertainty about the risk that it should be dealt with.

Surviving the end

Despite those four major risk areas, mercifully there's no guarantee that a disaster would take out every single person on the planet. It's a small comfort, but as Sandberg puts it, "You can totally imagine someone holed up in a Walmart with a can opener."

As long as whatever disaster, or confluence of disasters, that befalls us leaves behind at least a few survivors, there could be hope. How many humans it would take for humanity to pull through remains up for debate. Depending who you ask, it could be from a thousand on up. Those people would still have to survive whatever other challenges cropped up along the way.

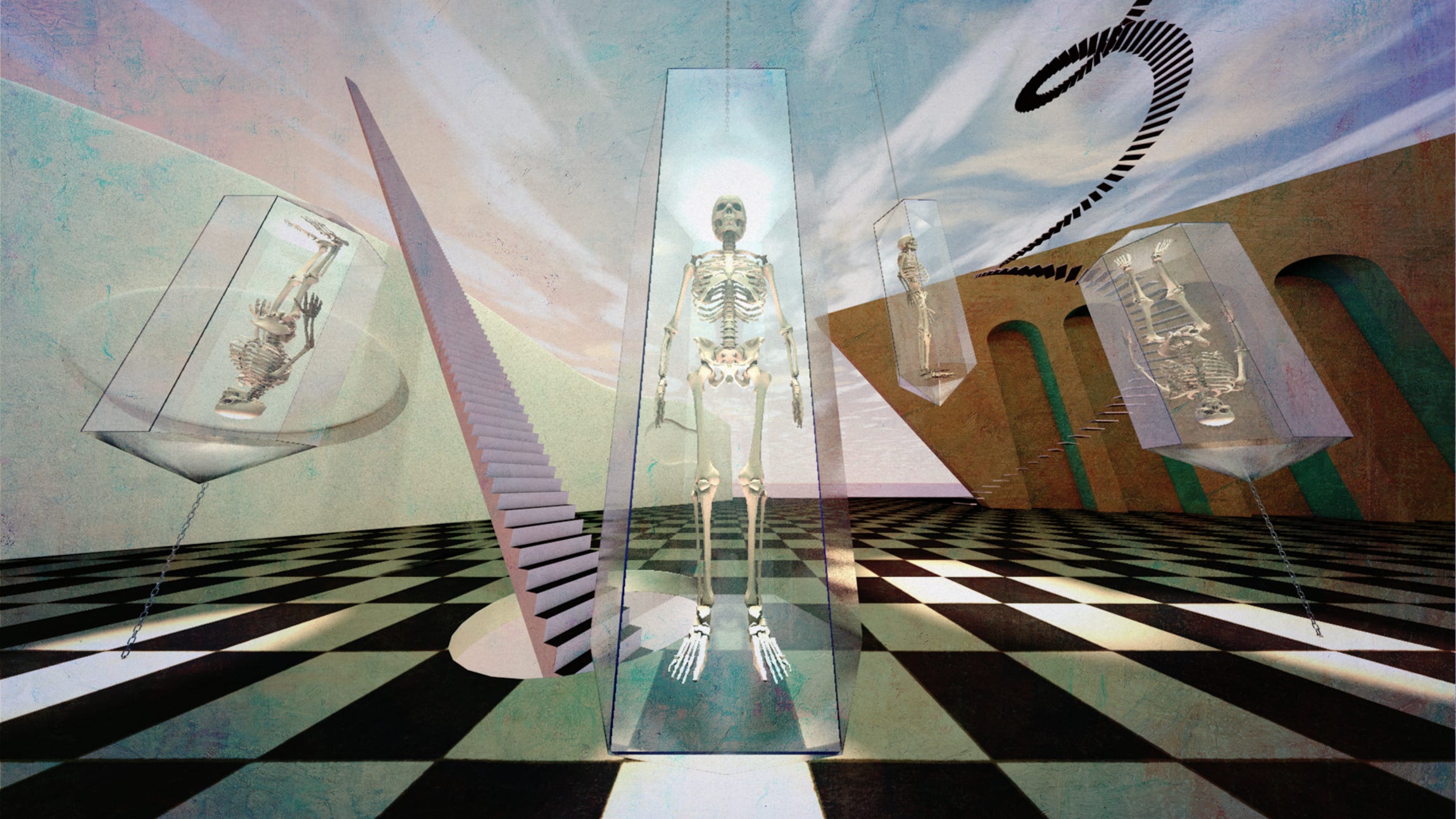

Stainless steel preservation chambers inside Alcor's facility.

"We still don't really understand the resiliencies of our societies," Sandberg says.

As impossibly grim as humans' prospects may look, even some of those people who ponder existential risk every day don't think humans are entirely down and out. At least not yet.

One key difference between humans and every other living thing on the planet is that humans have the ability to change their opinions of the world and to course-correct, Moynihan says. But just because we can change our ways, doesn't mean we always do.

"I think the future could be better in ways that we can't even comprehend," he says, "But that doesn't mean that it will be. What's worth fighting for is that ability for us to revise ourselves, correct the errors of the past, and continue muddling through."

Sandberg, meanwhile, wears a stainless steel medal on a chain around his neck everywhere he goes. He thinks of it as a secular St. Christopher medal -- the patron saint of travelers. Instead of featuring the third-century saint, this medal has instructions on what to do with Sandberg's body if he dies.

Pump it full of heparin; freeze quickly.

Sandberg's head is set to be frozen by the Alcor Life Extension Foundation and, ideally, revived in some far-off era.

The decision to join Alcor was made, in part, out of curiosity about what the future will be like -- pending many, many questions, both practical and existential as to whether this experiment works -- and to some extent, a dash of faith in the future.

"I am an optimist," Sandberg says, "the future could be awesome. I think the world is actually really good. And it could be even better, much better, which means that we have a reason to try to safeguard the future."