Pinnacle engine: Two pistons, one explosion

A small company called Pinnacle Engines wants to radically change the internal combustion engine. Instead of a cylinder head, combustion pushes two cylinders away from each other in the same cylinder, leading to more efficiency.

Over the roar from a 110-cc, two-cylinder engine, Pinnacle Engines founder James Cleeves (nicknamed Monty), pointed out a window in the block.

"You can see the cylinder sleeve moving for the intake stroke," he yelled over the din. Mostly what I could see was oil bubbling in the tiny window, hidden behind the spinning bands driving the camshafts. On the other side of the block was a bigger belt, joining the engine's two crankshafts and spinning at 4,000rpm, the current test speed. The safety glasses I was issued on entering the test room would be little help if the belt snapped.

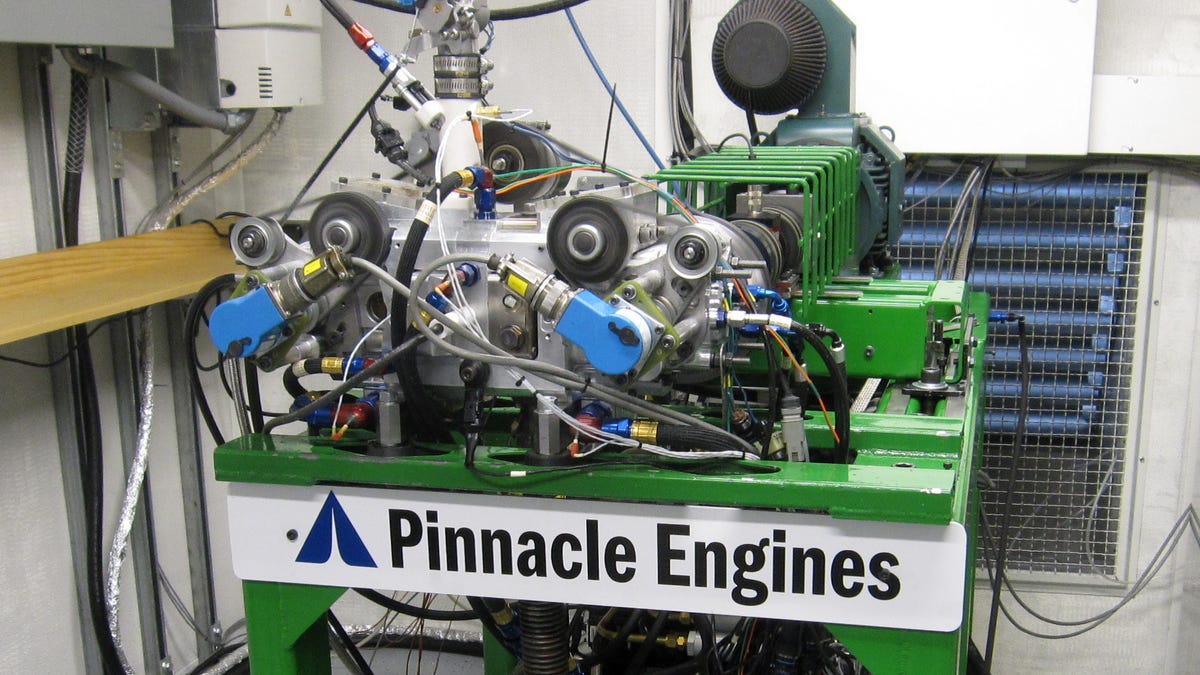

This was the engine test cell at Pinnacle Engines in San Carlos, Calif., a soundproofed room containing the most recent prototype of this innovative new engine design. The engine sat on a test stand, hooked up to sensors monitoring every aspect of its operation, from torque output to emissions.

On the other side of a window sat two of Pinnacle's employees, but their eyes were not on the engine. They gazed at computer monitors showing graphs and digital data of the engine's operation. From the computer, they could change the engine speed, adjust the fuel mixture, and change other operating parameters. Their work will eventually go into the production engine's control module as firmware setting a variety of performance parameters to make sure the engine runs as efficiently as possible.

This particular engine build was being tested for Pinnacle's first production engine, which will be used on a motorcycle for an undisclosed Indian company, hence its low displacement. The test engine wasn't optimized for quiet running, but I did notice something pleasant in its note. Rather than a heavy blatt-blatt, it produced a light burbling sound.

Which leads me back to the engine's configuration. Most internal combustion engines in use today have a single piston per cylinder. An air-fuel mixture sprays into the cylinder on the intake stroke, then the piston rises toward the cylinder head, compressing the mixture. At some point on the compression stroke, the spark plug ignites the fuel, creating an explosion that pushes the piston down. The piston's motion turns a crankshaft. Car engines tend to have four to eight of these pistons turning the same crankshaft.

The Pinnacle engine operates similarly, except that each cylinder contains two pistons, opposing each other. The air-fuel mixture flows between them, and the subsequent explosion pushes the two cylinders apart, turning two crankshafts.

A key difference in Pinnacle's engine lies in its intake and exhaust valves. Unlike the poppet valves opening up the top of a cylinder in current engines, Pinnacle's entire cylinder liner moves, actuated by a camshaft. On the intake side, the liner pulls back, revealing an intake port that circles the middle of the cylinder. Fuel pours in through this opening until the liner moves back up. The exhaust side works similarly. Cleeves says this method of intake lets him control the turbulence of the air fuel mixture as it enters the cylinder, making for a more optimized burn.

Although the valve configuration differs, the cylinder liners are still moved by camshafts, which lets Pinnacle use conventional variable valve timing technology. And while the current incarnation of the engine uses port injection, it could also use direct injection. In the initial demonstration version of the engine, two spark plugs ignite the fuel mixture in each cylinder, but the initial production version will probably use a single spark plug to help keep costs down.

On its Web site, Pinnacle claims its engine runs 30 percent more efficiently than traditional internal combustion engines. Cleeves gave me slightly different figures, which still represented an efficiency increase. Using base theoretical number crunching, which Cleeves described as "hand-waving," he said the current Pinnacle Engines technology would increase fuel economy in a Fiat 500, equipped with the very efficient 800-cc TwinAir engine, from 38 mpg to 42 mpg. Using some more efficiency technology Pinnacle has on the drawing board would increase the number from 42 mpg to 48 mpg.

Cleeves also cited a study he did comparing the Pinnacle engine with Ford's new 1-liter EcoBoost engine. Where the Ford engine gets 45 mpg, the Pinnacle engine, when also equipped with direct injection and a turbocharger, could produce 55 mpg. Pinnacle expects to have solid, tested efficiency numbers for its engine early next year.

A definite improvement comes in cost, according to Pinnacle. Without the need for heads, and only half the intake and exhaust valves, the Pinnacle engine would cost less than a traditional engine with the same amount of cylinders. But the company's current client wants to use the Pinnacle Engine as a replacement for a single-cylinder engine, not an optimal comparison. However, Pinnacle said it managed to match the production cost of the other engine.

Given the huge number of small engines used in Asia for motorcycles and three-wheel delivery carts, Pinnacle CEO Ron Hoge says the company could easily support itself off that clientele alone. But he has bigger ideas. In our meeting, he cited a number of instances where major automakers used an engine from a third-party manufacturer, at the same time acknowledging the difficulty of getting into the supply chain of a Ford or GM.

For now, Pinnacle is refining the engine design for its current client, but that client will actually do all the manufacturing. Hoge thinks that Pinnacle can eventually set up its own plant, but wants to keep the company's brain trust, the designers and engineers, in the San Francisco Bay Area, a place known for startups of a different nature.