Worried about Net neutrality? Maybe it's the FCC that should really concern you

A court decision to throw out the FCC's Open Internet rules actually made the agency stronger than ever. CNET's Maggie Reardon explains why you should be concerned.

The FCC may have lost its battle in federal court last week to enforce its Net neutrality rules, but the ruling actually gave the agency what some are calling unlimited authority to regulate almost every aspect of the Internet.

The decision by the US Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia was initially deemed a blow to the principles of an open Internet and to attempts by the Federal Communications Commission to enforce them. But the simple truth is that last week's decision marked a big victory for the FCC.

The reason: While the court deemed that the FCC's Open Internet rules were based on faulty logic, it gave the agency a blueprint to revise its argument so that the rules would stick. More importantly, the court sided with the FCC over the argument of whether the agency even has the authority from Congress to regulate the Internet. On that question, the FCC won. And it won big.

Ultimately, the commission ended up with even more influence over how the Internet operates in the future. All of this power concentrated in the hands of the FCC, aka the government, is dangerous, critics say. Simply look at the National Security Agency for a cautionary tale.

"The FCC has far more power than it did before this decision," said Harold Feld, senior vice president with Public Knowledge, a nonprofit that says it's devoted to preserving the openness of the Internet. "Before it was always unclear what the FCC's limitations were."

In other words, before this decision was handed down from the court, there was some haziness about the true role of the FCC in regulating the Internet. But since the court's decision, it's crystal clear: the FCC and even local public utility commissions can now impose regulations on the Internet, overriding any local or state laws that may forbid such regulation.

With the appropriate legal arguments, the FCC not only has the authority to tell broadband providers they can't block or discriminate against traffic on their networks -- that is, to enforce Net neutrality -- but it also has the authority to regulate broadband rates, as well as regulate pricing for all services connected to the Internet, from streaming video services like Netflix to Internet-based home surveillance services. It might even give the FCC authority to insert itself into copyright disputes.

It's this broad interpretation of the FCC's authority to regulate the Internet that has some critics wondering if the pendulum has swung too far.

"That kind of authority has to be really tempting," Feld said.

How this happened

In its decision, the court agreed with the FCC's arguments that Section 706 of the Communications Act gives it authority to regulate broadband networks, including imposing Net neutrality rules on these operators. But what it rejected was the agency's legal basis for enacting such rules.

Specifically, the court found that the FCC could not regulate broadband under common carrier rules as it had argued, because it had not classified the service as a telecommunications service. In other words, the court said the FCC cannot classify a service as one thing and regulate it as if it's another. It cannot contradict the statute.

The fix to this problem is simple, the court reasoned. The FCC can simply reclassify broadband services as telecommunications services.

Barring that limitation, under its new powers, the only thing the FCC needs to show when regulating a service is that the regulations it's imposing will "encourage the deployment...of advanced telecommunications capability." The court also said that the commission has the authority "to regulate broadband providers' economic relationships with edge providers if, in fact, the nature of those relationships influences the rate and extent to which broadband providers develop and expand services for end users."

This might include, "price cap regulation, regulatory forbearance, measures that promote competition in the local telecommunications market, or other regulating methods that remove barriers to infrastructure investment."

What the FCC's expanded power means to the Internet

Feld said this could have huge implications for every facet of the Internet. Not only should this scare broadband providers, but, he said, Google, Amazon, Netflix, and any other company operating on the Internet -- what the court calls "edge providers" -- should be concerned about the unfettered power the US District Court has given the FCC. Feld said the FCC's authority could even extend to content providers who use the Internet to distribute content.

This is exactly why Judge Laurence Silberman of the US Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit dissented in part to the court's ruling. Even though he agreed with his colleagues that the FCC could not regulate broadband service under common carrier rules, he disagreed with the other justices when it came to their interpretation of the FCC's authority for regulation. And he said the decision grants the "FCC virtually unlimited power to regulate the Internet." He said just as this very court noted in its Comcast v. FCC decision in 2010, this reading of the Communications Act, "would virtually free the Commission from its congressional tether."

FCC says there's no reason to fear

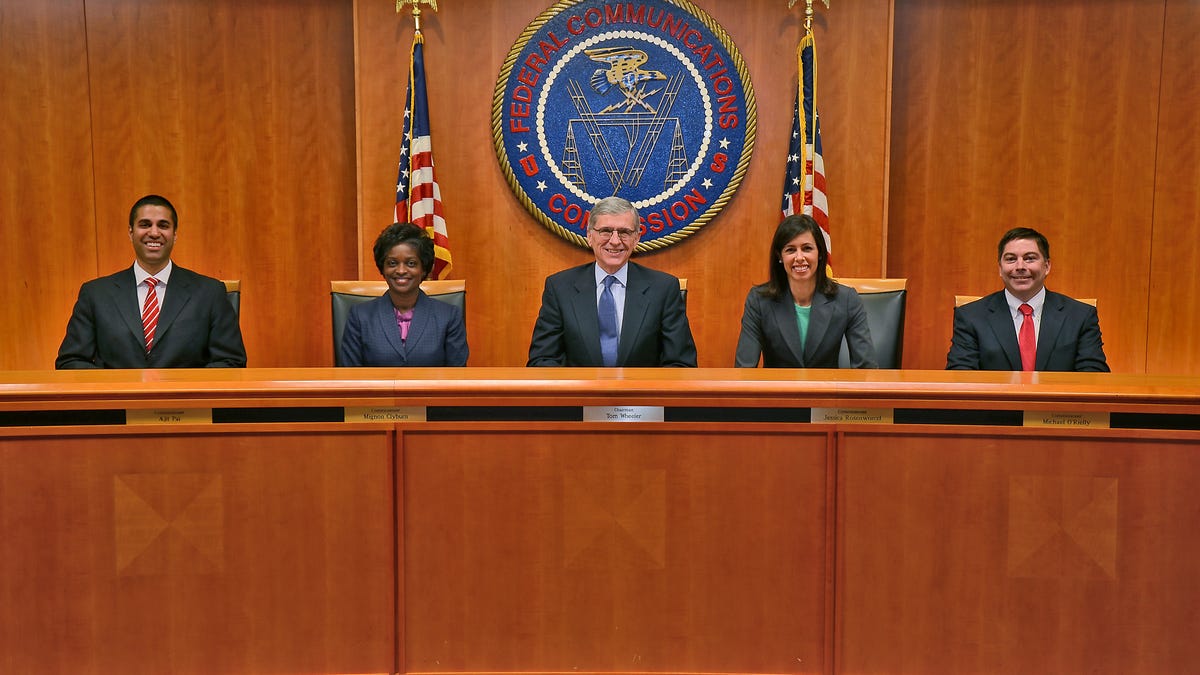

FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler has said that Internet companies, broadband providers, and citizens who have come to rely on the Internet have nothing to fear. His FCC has no intention of using its newfound powers to over-regulate the industry. He tried to reassure broadband providers and others in a blog post published last week that the FCC is "not going to take over the Internet," or "dictate the architecture of the Internet."

"It is not going to do anything that gratuitously interferes with the organic evolution of the Internet in response to developments in technology, business models, and consumer behavior," he added.

But he also reiterated that the FCC "is not going to abandon its responsibility to oversee that broadband networks operate in the public interest." And he said the agency won't ignore the fact that "when a new network transitions to become an economic force...economic incentives begin to affect the public interest."

While he stated that the FCC's authority to regulate broadband networks had always been the intent of Congress, he tried to reassure the public that under his watch he would make sure the agency does not use its powers gratuitously.

"How jurisdiction is exercised is an important matter," he said. "It is important not to prohibit or inhibit conduct that is efficiency producing and competition enhancing. It also is important not to permit conduct that reduces efficiency, competition, and utility, including the values that go beyond the material."

In short, he said he has no intention of imposing regulation for the sake of regulating. But he said he plans to protect the openness of the Internet to maintain "our networks as conduits for commerce large and small, as factors of production for innovative services and products, and for channels of all of the forms of speech protected by the First Amendment."

But even as Chairman Wheeler tried to allay fears of an over reaching FCC, he has done little in his comments to provide a clear picture of how the FCC will actually make sure the Internet stays open and how it will handle regulating other aspects of broadband services. In fact, his "common law" approach, which will look at potential Net neutrality violations on a case-by-case basis, has likely caused more uncertainty in the market. And even if Wheeler's FCC is judicious in its regulatory implementation, it's difficult to say what the next FCC would do with all this power.

Public Knowledge's Feld said it's this uncertainty that should bother any company or individual on the Internet.

"No one got what they wanted out of this decision," Feld said. "Confusion over the proper role of the FCC is greater than ever."