Wireless providers side with cops over users on location privacy

The trade association representing AT&T, Verizon, and Sprint opposes a California proposal for search warrants to track mobile devices, claiming it will cause "confusion."

The nation's largest wireless providers oppose a proposed California location privacy law that would require police to obtain search warrants to track a wireless customer's whereabouts, CNET has learned.

They're criticizing a new state bill, S.B. 1434, that would require a judge to approve requests for location tracking except in certain emergency situations. S.B. 1434 would also require wireless providers to divulge "the number of times location information has been disclosed," and how many times they rejected police requests.

Their criticism comes as concerns about warrantless location surveillance, a practice that the Obama administration and law enforcement agencies have defended, are growing. Federal legislation introduced last year would require police to obtain a warrant signed by a judge before monitoring someone's movements, and courts have split over whether warrantless tracking is constitutional or not.

Requiring a warrant to track California residents would "create greater confusion for wireless providers when responding to legitimate law enforcement requests," says the letter (PDF) written by CTIA, a wireless trade association that counts AT&T, Verizon Wireless, U.S. Cellular, and Sprint Nextel among its board members. CTIA sent the letter to bill sponsor Mark Leno, a Democratic state senator whose district includes the city of San Francisco. CTIA also opposes the reporting requirements of S.B. 1434, saying they would "unduly burden wireless providers and their employees, who are working day and night to assist law enforcement to ensure the public's safety and to save lives."

"Wireless companies should be working day and night for us, their customers, not law enforcement," replies Nicole Ozer, technology and civil liberties policy director at the ACLU of Northern California.

"This bill is good for consumers and it's good for business," Ozer told CNET. CTIA "shouldn't be opposing this bill. They shouldn't be opposing the warrant requirement. And they shouldn't be opposing the basic reporting requirements to make sure the law is being followed." (In a subsequent blog post, Ozer asked ACLU supporters to take to Twitter to criticize CTIA's position.)

By advancing this argument, CTIA risks creating the perception that its member companies are happy to open their databases of customers' GPS coordinates to law enforcement -- just so long as nobody knows about it.

Jamie Hastings, vice president, external and state affairs for CTIA-The Wireless Association, sent CNET a statement this morning saying:

CTIA and its members oppose S.B. 1434. If this bill was enacted, it would mandate burdensome reporting requirements for wireless carriers. We also have concerns with the warrant provisions in the bill because the definitions appear overly broad. We are seeking clarification within this section to ensure that wireless providers can provide lawful and timely information to legitimate law enforcement requests and that there are no conflicts with federal law while protecting consumers' privacy.

AT&T, one of CTIA's largest member companies, is also part of the Digital Due Process coalition, which has taken the opposite position. It's lobbying for laws saying that location data should be disclosed only with a search warrant.

Wireless providers already compile many of the records required to be disclosed by S.B. 1434. It's for billing purposes: because they're paid for assisting surveillance requests, they keep the records so they can send accurate invoices to law enforcement.

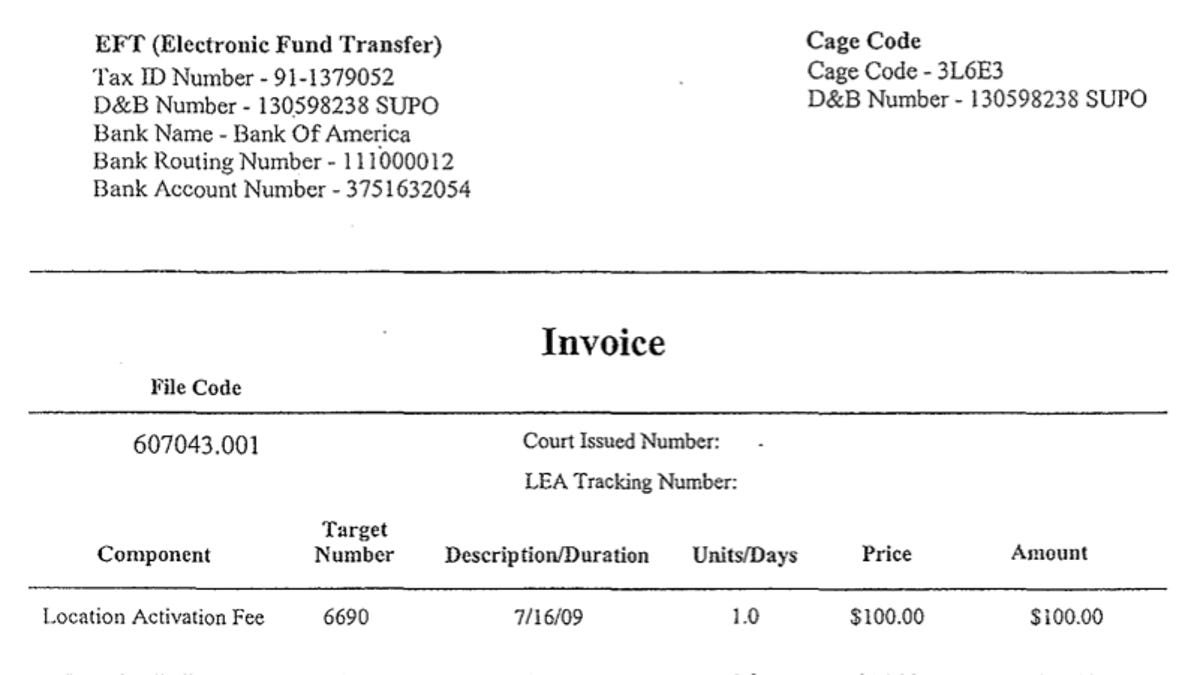

The ACLU recently posted over 5,000 pages of internal government documents, which show that Verizon Wireless sent the Raleigh, N.C. police department an invoice (PDF) of $45 after it turned over cell site information on a customer. MetroPCS charges $50 for "detail records," and AT&T charges a $100 activation fee and $25 a day for location tracking.

In addition, some companies, including Google, already publish data about how frequently they comply with law enforcement requests.

Google voluntarily does this with its interactive Transparency Report. And the OpenNet Transparency Project -- a project of the Berkman Center for Internet and Society at Harvard University and other universities -- is hoping to make that kind of voluntary disclosure more mainstream.

Even though police are tapping into the locations of mobile phones and planting GPS bugs on vehicles thousands of times a year, the legal ground rules remain unclear, and federal privacy laws written a generation ago are ambiguous at best. Courts have split over how easy it should be for police to track Americans electronically and whether the same rules should apply to live tracking and obtaining stored information about someone's earlier whereabouts.

In April 2011, the Obama Justice Department launched a frontal attack on the idea of requiring search warrants for locations, with James Baker, the associate deputy attorney general, telling a Senate panel that such a requirement would hinder "the government's ability to obtain important information in investigations of serious crimes." Previously, the department had argued in court that warrantless tracking should be permitted because Americans enjoy no "reasonable expectation of privacy" in their, or at least their cell phones', previous locations.

Not too long ago, the concept of tracking cell phones would have been the stuff of spy movies. In 1998's "Enemy of the State," Gene Hackman's character warned that the National Security Agency has "been in bed with the entire telecommunications industry since the '40s -- they've infected everything." But after a decade of appearances in the likes of "24" and "Live Free or Die Hard," location-tracking has become such a trope that it was satirized in a scene with Seth Rogen in "Pineapple Express" (2008).

CNET was the first to report on the Justice Department's use of warrantless prospective cell tracking, meaning information about a person's future whereabouts, in a 2005 news article.

Last updated at 11 a.m. PT.