Why you should care about Net neutrality (FAQ)

A federal appeals court has thrown out the FCC's Net neutrality rules. CNET's Maggie Reardon explains what the ruling means to the average consumer -- and why it really, really matters.

The US Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit on Tuesday struck down rules adopted by the Federal Communications Commission in 2010 meant to protect the openness of the Internet.

What does this ruling -- and the principles of Net neutrality that it affects -- mean to the average Internet user? While the legal arguments may seem complicated and arcane, the reality is that this court decision has the potential to alter the future of the Internet as we know it. Whether you think these changes will harm consumers or benefit them depends on whom you choose to believe in this ongoing debate.

To help readers get a better understanding of what the court's Net neutrality decision means and to get a handle on what the potential outcomes might be, CNET has put together this FAQ.

What are the Open Internet rules?

Adopted by the FCC in late 2010, the Open Internet regulations are supposed to provide a set of rules to ensure that broadband service providers preserve open access to the Internet.

There are three main rules at the heart of the regulation. The first required that broadband providers, whether they're fixed-line providers or wireless operators, are open and transparent to their customers and to the services using their networks about how they manage congestion on the systems.

The second rule prohibited broadband operators from blocking lawful content on their networks. Here, there's some difference in strictness depending on whether the provider deals in fixed-broadband or wireless services. Fixed-broadband providers, such as cable operators and DSL providers, have abided by a more stringent set of rules, and wireless operators adhered to a less strict version of the rules.

And the third rule, which applied only to fixed-broadband providers, prohibited "unreasonable" discrimination against traffic on their networks.

What happened on Tuesday?

In 2011 after the FCC's rules were published and set into action, Verizon Communications challenged those rules in court, arguing that the FCC had no authority from Congress to impose such rules and that the rules stymied its First Amendment rights.

On Tuesday, the federal Court of Appeals for the DC Circuit ruled in a 2-1 decision that even though the FCC has the authority to regulate broadband access, it based these rules on a flawed legal argument. In other words, the FCC based its Net neutrality regulation on a law that does not apply to broadband providers.

Specifically, the court said that since the FCC has classified broadband providers differently than it has classified telecommunications providers, it cannot use statutes that pertain to telecommunications services as a basis for regulation on broadband services.

From the decision:

Even though the commission has general authority to regulate in this arena, it may not impose requirements that contravene express statutory mandates. Given that the commission has chosen to classify broadband providers in a manner that exempts them from treatment as common carriers, the Communications Act expressly prohibits the commission from nonetheless regulating them as such. Because the commission has failed to establish that the anti-discrimination and anti-blocking rules do not impose per se common carrier obligations, we vacate those portions of the Open Internet Order.

What is a "common carrier," and how does the term relate to this specific case?

The basis for the Net neutrality regulation that the FCC implemented is predicated on a centuries-old legal concept known as "common carriage." This concept of "common carriage" has been used not just to regulate telecommunications but other industries as well. It was developed to ensure that members of the public retained access to fundamental services that use public rights of way. In the case of the Internet, it means that the infrastructure used to deliver Web pages, video, and audio-streaming services, and all kinds of other Internet content, should be open to anyone accessing or delivering that content.

Other examples of common carriage include transportation services. For example, a ferry operator under the common carrier concept is free to operate a business transporting people and goods across a river, but because he is using a public waterway, he's required to provide service to everyone. He cannot indiscriminately choose to service some customers and not others. And while the ferry operator can determine the price for his services, the prices must be fair and reasonable.

Throughout the 20th century this concept was applied to telecommunications services to ensure that phone companies, which use public rights of way to string wire and cable, service all customers.

Early in the last decade, there was a debate in communications policy circles about how broadband should be regulated. Should it be a telecommunications service subject to "common carrier" regulation like the traditional telephone network? Or should it be classified as an information service, which would exempt it from these "common carrier" requirements?

In 2005, the US Supreme Court ruled in its Brand X decision that broadband services should not be classified as telecommunications services. Therefore, because broadband is not a telecommunications service, broadband providers' infrastructure is not considered a public right of way and should not be regulated under the common carrier concept.

It's this decision that forms the basis of Tuesday's appeals court ruling. The reason the appeals court rejected the FCC's position is that the FCC was using a legal argument that placed "common carrier" requirements on a service the that Supreme Court ruled in Brand X is not subject to those requirements.

Does this mean the FCC has no authority to regulate the Internet?

No, not at all. In fact, the court rejected Verizon's argument that Congress did not give the FCC jurisdiction over broadband access:

The Commission has established that section 706 of the Telecommunications Act of 1996 vests it with affirmative authority to enact measures encouraging the deployment of broadband infrastructure. The Commission, we further hold, has reasonably interpreted section 706 to empower it to promulgate rules governing broadband providers' treatment of Internet traffic, and its justification for the specific rules at issue here -- that they will preserve and facilitate the "virtuous circle" of innovation that has driven the explosive growth of the Internet -- is reasonable and supported by substantial evidence.

This part of the decision is an important victory for the FCC. If the court had sided with Verizon on this argument, then it would have called into question the agency's authority to institute any regulation pertaining to the Internet or broadband providers.

I thought an appeals court already struck down Net neutrality? How is this decision different?

In April 2010, the same appeals court that handed down Tuesday's decision also decided a case that pitted the FCC against Comcast. In that case, Comcast had challenged the FCC's decision to punish the cable operator for slowing or throttling BitTorrent traffic as a way to manage its traffic. In that decision, the appeals court agreed that the FCC does not have the legal authority to enforce Net neutrality regulations on Internet providers. At the time, the FCC had not adopted official rules regulating Net neutrality. Instead, the agency imposed penalties on Comcast for violating Net neutrality principles it had in place.

After this court decision, a new Democratic FCC was installed. And the FCC, then headed by President Obama's former law school classmate Julius Genachowski, adopted formal Net neutrality rules. And it's these official rules and regulations that Verizon challenged in the federal appeals court case that was decided Tuesday.

Does this mean that the FCC's Net neutrality rules don't apply to any broadband provider?

The court's decision applies to all Internet and broadband service providers, except for one: Comcast. As part of conditions it agreed to when it purchased NBCUniversal, Comcast said it would abide by the FCC's Open Internet rules for seven years, even if the rules were modified by the courts.

"Comcast has consistently supported the Commission's Open Internet Order as an appropriate balance of protection of consumer interests while not interfering with companies' network management and engineering decisions," Comcast's executive vice president, David Cohen, said in a statement. "We remain comfortable with that commitment because we have not -- and will not -- block our customers' ability to access lawful Internet content, applications, or services. Comcast's customers want an open and vibrant Internet, and we are absolutely committed to deliver that experience."

Cohen went on to say that his company plans to work with FCC Chairman Wheeler and the rest of the FCC to find "an appropriate regulatory balance going forward that will continue to allow the Internet to flourish."

What does this decision mean for me, the average Internet user?

Whether you think this decision is a good thing for the average Internet consumer depends on which side of this political debate you sit on.

The first thing you need to keep in mind is that nothing will change for consumers right away. As with most major court decisions, there won't be any immediate fallout.

But what this court decision does do is pave the way for changes in Internet service business models in the future. And that could have a huge effect on the services that consumers use.

For instance, the ruling opens the door for broadband and backbone Internet providers to develop new lines of business, such as charging Internet content companies, like Netflix, Amazon, or Google, access fees to their networks. Companies like Verizon, AT&T, Time Warner Cable, Comcast, and others could offer priority access over their networks to ensure streaming services from a Netflix or Amazon don't buffer when they hit network congestion, providing a better experience for end users.

Wireless providers like AT&T have already proposed a plan in which app developers and other Internet services could pay for the data consumers use to access their services. Again, AT&T argues this service is a win for consumers since it saves them money by not requiring them to use the any of the data they pay for monthly.

Broadband-service providers claim that these new services and business models will benefit consumers by offering better service quality or defraying costs. Broadband providers also claim having this freedom to establish new lines of revenue will enable them to invest more in their networks, which ultimately benefits consumers.

Randal Milch, Verizon's executive vice president, head of public policy, and general counsel, said that the court's decision will ultimately lead to carrier innovation and that consumers will eventually have "more choices to determine for themselves how they access and experience the Internet."

But supporters of Net neutrality caution this is a very slippery slope. And they argue that these new business models will likely increase costs for companies operating on the Internet, and that eventually those costs will be passed onto consumers. What's more, erecting priority status for services online will result in bigger players being able to afford to pay the fees, while smaller upstarts will be blocked from competing because they won't be able to afford the fees that a Verizon or Time Warner Cable might impose.

Harvey Anderson, senior vice president of business and legal affairs for Mozilla, said the court's decision is alarming for Internet users because it will also provide broadband operators the legal ability to block any service they choose, which will undermine the once "free and unbiased Internet."

Michael Beckerman, president and CEO of the Internet Association, a political lobbying organization formed by members of the Internet industry, including Google, Facebook, and Amazon, argues that without any rules in place to protect the openness of the Internet, innovation on the Internet will be in jeopardy. He says that companies like Google, Facebook, and Amazon have been able to thrive because of the Internet's "innovation without permission" ecosystem, which provides a low barrier of entry to anyone with an idea. He cautions that the success of the Internet to date should not be taken for granted.

"The Internet Association supports enforceable rules that ensure an open Internet, free from government control or discriminatory, anticompetitive actions by gatekeepers," he said in a statement.

But I'm still not sure how that affects me. Does this mean my broadband provider will likely start charging me more for a prioritized service?

It's a possibility. Your broadband service provider could establish a service in which Gold customers pay more and are guaranteed a certain quality of service over Silver or Bronze customers.

But what's more likely to happen is that broadband providers will strike deals with content providers, as I mentioned above. And this will indirectly affect consumers potentially in negative and positive ways. On the positive side, video streaming services could get more reliable. The experience may be improved for customers willing to pay more for service.

There are also some potential negative consequences. If Internet startups' innovation is stifled, because they can't afford to "pay to play," then fewer new services will be available. But these types of services also set the stage for consumers to be caught in the middle of disputes between large companies over service fees.

For example, Time Warner Cable and CBS were in a knock-down-drag-out fight this past summer over how much Time Warner Cable would pay to retransmit CBS broadcast content over Time Warner's video service. The dispute resulted in CBS broadcasts being blacked out for several weeks for Time Warner video subscribers. (Disclosure: CNET is owned by CBS.)

Imagine if cable companies charged Internet companies to transmit their services to consumers. And imagine if there was a similar breakdown in negotiations between Time Warner Cable and Amazon or Google over these fees. Without any regulation prohibiting Time Warner from blocking access to a service or a Web site, Time Warner could block consumers' access to Amazon or Google until the fee dispute was settled.

There's no question that this could hit consumers.

Does the DC Circuit really think that the broadband providers can be trusted without any rules?

Actually, the court accepted the FCC's reasoning behind why it felt Open Internet rules are necessary. But the judges said that the legal basis for the rules -- that is, basing the rules on the concept of common carriage -- was not appropriate.

"Equally important, the commission has adequately supported and explained its conclusion that, absent rules such as those set forth in the Open Internet Order, broadband providers represent a threat to Internet openness and could act in ways that would ultimately inhibit the speed and extent of future broadband deployment," the judges write. "Nothing in the record gives us any reason to doubt the commission's determination that broadband providers may be motivated to discriminate against and among edge providers."

What will happen next? Is the fight for Net neutrality over?

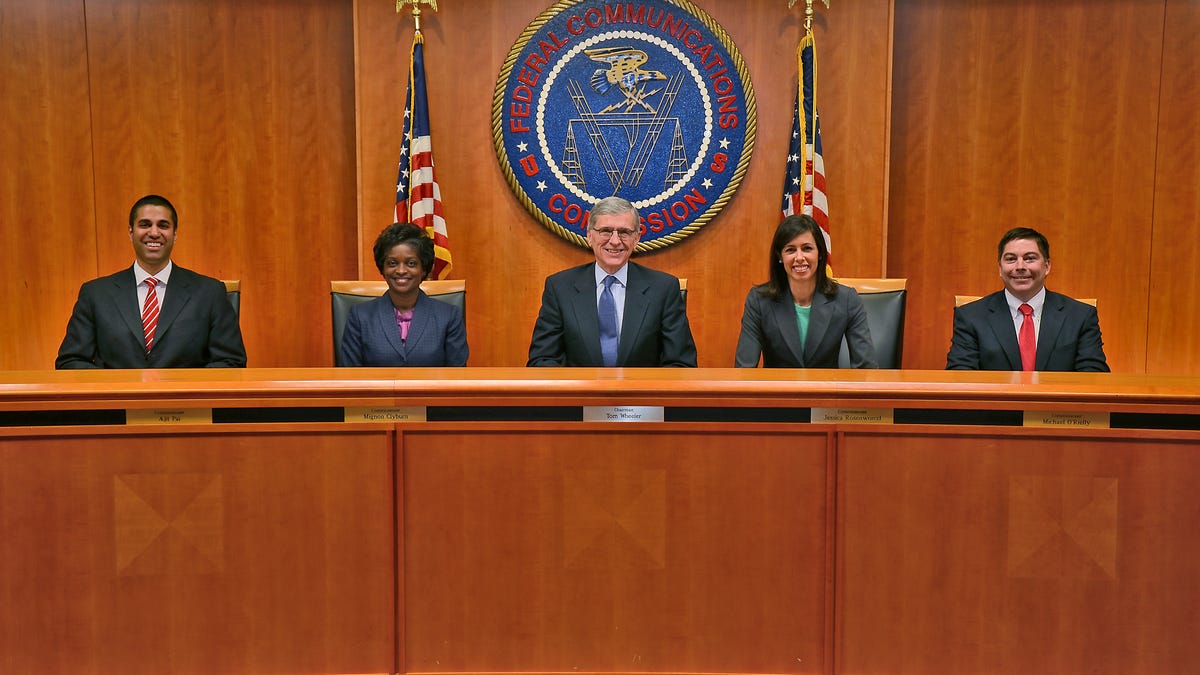

That's the big unanswered question. FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler said in his statement Tuesday that the agency is considering all its options, including an appeal. This could mean an appeal to the US Supreme Court. Consumer advocates, which were very pleased the court sided with the FCC regarding its authority to regulate broadband services, say the FCC should come up with new regulations that don't use common carriage as their legal basis.

There's always the possibility that Congress could pass legislation that spells out rules. But because Net neutrality is such a polarizing political issue and because of the dysfunction in Congress at the moment, it's more likely that the FCC will be forced to act.

Sen. Al Franken (D-Minn.), one of the most vocal lawmakers supporting open Internet rules, said Tuesday that Net neutrality is the free speech issue of our time. He added that it's a common-sense idea that big corporations like Verizon, Comcast, and Time Warner shouldn't control who gets to innovate, communicate, or start a business on the Internet. And he is urging the FCC to find a way to make rules that will not be challenged in court.

"Getting rid of Net neutrality is bad for consumers and the economy, plain and simple," he said in a statement. "And it's a real risk to the Internet as we know it. The FCC needs to respond immediately in a way that keeps the Internet open to all of us, not just big corporate interests."

One thing is certain, the Net neutrality debate is far from over. And this court decision is not the last you'll hear about the issue.