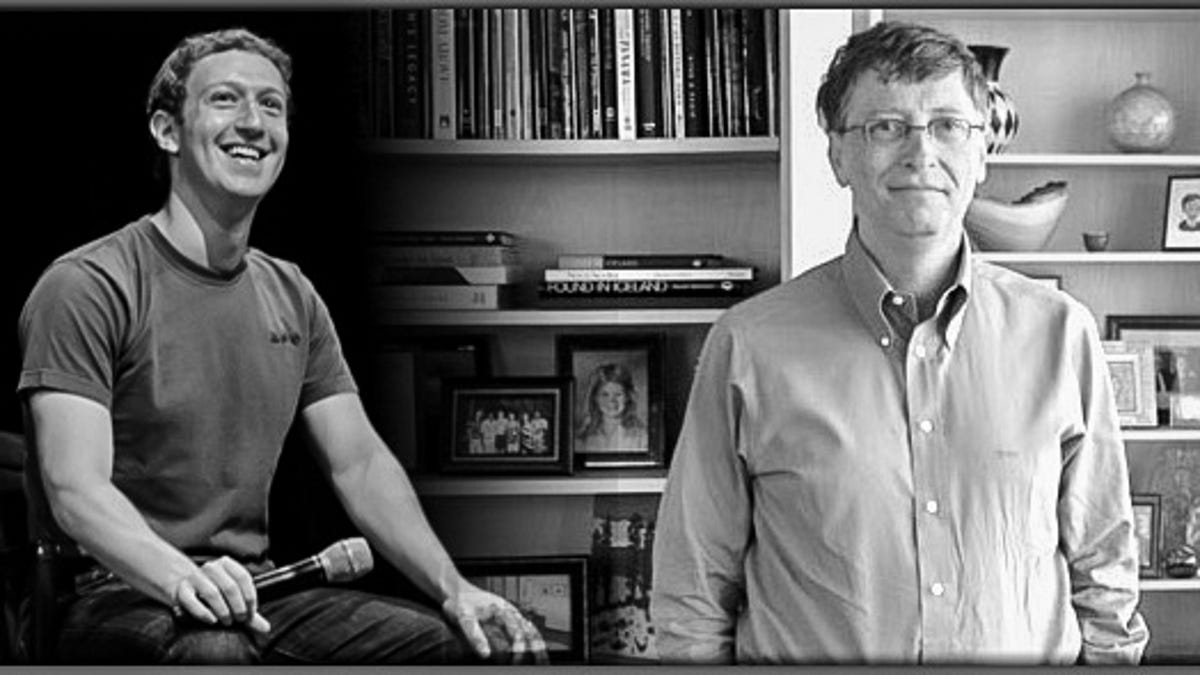

Why Mark Zuckerberg's future points to Bill Gates' past

Different eras and different technologies, but both moguls share a common trait when it comes to pursuing their enlightened self interest.

Gates has been doing this for decades. And while Zuckerberg's a veritable piker at this, Facebook's still-under 30 CEO has already mastered the art of saying little while the cameras whirr. Monday's Mobile World Conference chat offered a prime example of how the game gets played.

But one of Zuckerberg's passing comments to his on-stage interlocutor at MWC, David Kirkpatrick, also revealed a determination to pursue a policy of enlightened self-interest, where a company's success turns out to be a harbinger of social and economic change. That, too, is a remarkable trait he shares with Gates. More about that in a moment.

In talking up Facebook's participation in the Internet.org consortium, Zuckerberg painted his vision of a future in which hundreds of millions of new users living in industrializing nations access the Internet on their handsets for free or after paying a nominal charge. I'm sure the cynics will portray this do-gooder stuff in cartoonishly sinister ways. Something along the lines of: "Ah ha! More Internet equals more Facebook. More Facebook equals more more money for Zuckerberg and his cohorts as the stock keeps soaring."

In fact, it's a lot more complicated and it speaks volumes about the scope of Zuckerberg's ambition as well as his passion.

Facebook's success as a public company reflects the truism that mobile is fated to dominate computing's future (about 49 percent of its advertising revenue came from mobile products in its most recent quarter.) That shift in the way people access the Internet is another reason why Facebook's board thought it worth paying $19 billion for WhatsApp.. This is a story with many more chapters left to write. Earlier this year, Zuckerberg outlined his 10-year time frame to bring Internet access to the two-thirds of people on the planet who are not connected. If he can speed up that process, Zuckerberg will be helping to usher in an era where the majority of people using cheaper smartphones connected to the Internet will be living outside of the wealthy West. That's a very big idea.

Zuckerberg acknowledged in his Barcelona chat that this will take time and investment -- not to mention the active participation of myriad public and private partners -- but he makes a persuasive argument about how the spread of inexpensive handsets and inexpensive Internet connectivity would help chip away at the staggering global wealth inequalities that now exist in much of the world. If you increase the developing world's access to the Internet, the resulting infrastructure build-out would increase people's chances for better-paying jobs and improve their access to better health care. Obviously, if nations build up their Internet infrastructure, companies like Facebook will benefit. What's wrong with that?

The boldness in that idea reminded me of Gates' notion of a computer on every desk and in every home. That, too, was a business decision with revolutionary implications for society when he came up with it back in Microsoft's early days as a software startup in Albuquerque, N.M. That, too, was a gutsy, even outlandish idea at the time. Computing connoted expensive mainframes and minis while personal computers meant do-it-yourself kits for geeks with soldering irons.

Gates stuck with it. He enlisted partners like Intel who helped Microsoft bring PC prices down to affordable levels. Prices fell even as Moore's Law kicked in. By the 1990s, the concept of every computer-on-a-desk was no longer a pipe dream. Gates went on to become one of the world's richest people with Microsoft the industry's biggest software company. The pursuit of enlightened self-interest had changed the world.

A few decades later, Zuckerberg is giving that same idea another whirl.