US fires up X-ray tech to catch illegal drugs at the border

One drive-through scanner detected nearly 650 pounds of methamphetamine and the synthetic opioid fentanyl hidden under a load of cucumbers.

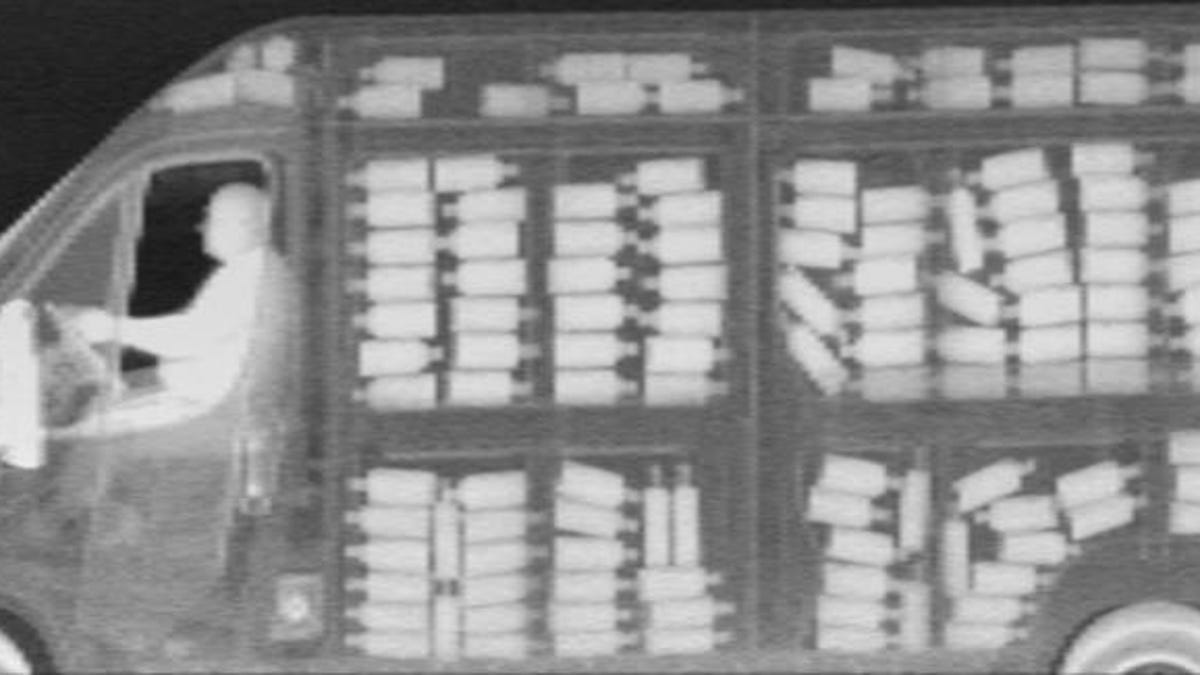

Backscatter X-ray imaging of a vehicle reveals smuggled bottles of alcohol, reportedly hidden to avoid paying duties.

A large tractor trailer filled with cucumbers pulled up to the Nogales border crossing in Arizona in January. The busy port of entry on the US-Mexico border sees more than 1,500 trucks pass through it daily, but something about this specific trailer made local officials suspicious.

Rather than waving the truck through, US Customs and Border Protection officers had a trained dog sniff around it and ran the vehicle through a room-size X-ray machine. What they saw in the grainy black-and-white X-ray images was jaw-dropping.

It turned out to be the largest stash of the synthetic opioid fentanyl ever seized in CBP history. Underneath those cucumbers, in a false floor in the rear of the trailer, was nearly 254 pounds of fentanyl and 395 pounds of methamphetamine -- with a street value of about $4.6 million.

"The size of a few grains of salt of fentanyl, which is a dangerous opioid, can kill a person very quickly," Michael Humphries, CBP's Nogales port director, said during a press conference at the time. "We'll use all our resources to prevent the entry of dangerous narcotics into the United States -- our officers, our technology, our canines and everything we can to throw back at them."

President Donald Trump says a physical border wall is necessary to stop the flow of drugs into the US. But data from CBP paints a different picture, showing that the majority of narcotics make their way into the country through ports of entry. In 2018, for example, 90% of heroin, 88% of cocaine, 87% of methamphetamine and 80% of fentanyl seized by officials was smuggled through legal crossings. At these ports of entry, the government is increasingly relying on X-ray technology to detect such illegal drugs.

Contraband seen in X-ray imaging of a cargo shipment.

It's not just drive-through scanners that agents are using. They also have smaller machines, similar to those that luggage goes through at the airport, and portable handheld X-ray devices that can target specific areas on a vehicle. CBP calls this tech "nonintrusive inspection systems" and says it allows agents to investigate more vehicles faster.

Some worry how exposure to the X-rays will affect people's health as they drive their vehicles through the machines. X-ray radiation is known to cause cancer and contribute to other health risks. The CBP says the machines' radiation is "low" and that it would take 2,000 exposures to equal one hospital chest X-ray.

In all, a CBP spokesman told CNET, the agency has more than 300 drive-through scanners, 3,500 small-scale X-ray machines and 35,000 handheld devices deployed at US ports of entry. In the 2019 federal budget, CBP received an extra $520 million for additional nonintrusive inspection technology at land border ports of entry.

"The focus is not just to replace aging systems," Robert Perez, deputy commissioner of CBP, said before the House Committee on Homeland Security on May 9, "but to transform port operations in order to expertly facilitate legitimate travel and trade, while successfully interdicting deadly fentanyl and other contraband."

The Drug Enforcement Agency, which is tasked with combating drug smuggling, declined to comment on its investigative techniques.

Scaling up

When the driver of the tractor trailer full of cucumbers slowly passed through the X-ray machine, his vehicle was hit from the top and on both sides with a type of imaging called backscatter. The machine then likely showed agents a series of black-and-white images of the truck that highlighted metallic and organic material, such as drugs.

That 649 pounds of fentanyl and methamphetamine hidden in the trailer's false floor probably lit up the images in bright white.

CBP has been using drive-through X-ray machines since 2008. The first machine, called a Z Portal, was set up in San Ysidro, California, which is the busiest land port of entry in the Western Hemisphere, according to the federal government. CBP has since put the scanners all along the southwest border. Z Portal's manufacturer, AS&E, didn't respond to a request for comment.

Viken Detection's handheld X-ray scanner can penetrate a car's steel exterior.

On an average day, CBP says more than 1 million travelers and $6.3 billion worth of legal cargo cross through the country's ports of entry. Screening each person and vehicle is nearly impossible, which is why the government has turned to X-ray tech.

"CBP consistently seeks advanced and novel solutions to assist officers," the CBP spokesman said. These new tools help the agency more easily inspect "smaller confined spaces to view inside fuel tanks and small compartments, behind walls of conveyances, and identify false walls in containers."

CBP awarded a $28.8 million contract last October to Viken Detection, which makes a handheld X-ray device called the HBI-120. Like the drive-through machines, these scanners also use backscatter imaging. Local law enforcement agencies and drug task forces have been using these handheld scanners for about a year.

Before X-ray imaging, officers would have to rip out door panels and dashboards and search tire wells if they were suspicious of a vehicle. When the large-scale X-ray machines came on the scene, they were powerful enough to see through a vehicle's thick steel exterior. But it wasn't until the past couple of years that smaller devices could handle this type of imaging.

"These officers had a screwdriver or canine unit to try to find stuff, and now they're literally finding things in minutes that would take them hours before," Jim Ryan, CEO of Viken Detection, said in an interview. "With our instruments we can basically walk around the vehicle, put our handheld instrument up to it and scan."

When using the HBI-120, officers will see images scroll by that are typically dark. But if they scan over organic material, like a package of drugs or bundle of cash, they'll see an intense white signal.

"It won't tell you exactly that it's this type of drug or that type of drug," Ryan said. But "you'll be able to see those drugs hidden in parts of vehicles that shouldn't have lumps of organics in them."

Viken Detection is also developing a drive-through scanner called Osprey. Both the CBP spokesman and Ryan said the government is stepping up large-scale X-ray imaging of vehicles at the border. Ryan likened the increased scanning to when the Transportation Security Administration decided to screen all checked baggage going onto airplanes after 9/11.

"Basically the goal is, can we start screening privately owned vehicles crossing the border at a much larger scale than what they're doing today," Ryan said. "Now it's a matter of how do we get the best technology, something that's future-proof."