Tim Cook: Encryption fight puts Apple in a 'bizarre position'

In an interview with Time, Apple's CEO says his company's battle with the US government over access to an iPhone has been like a "bad dream."

Fighting the US government over the issue of iPhone encryption makes Tim Cook uncomfortable. But Apple's CEO feels he would have sold out had his company given in to all of the feds' demands.

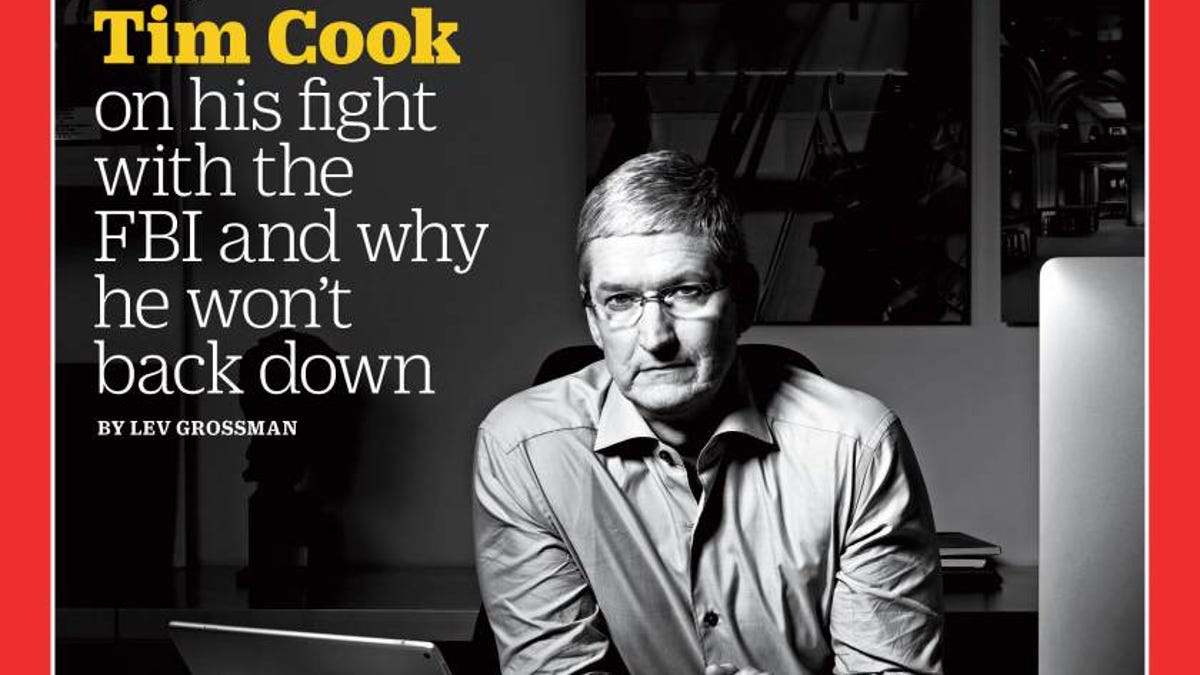

Cook spoke with Time magazine for a cover story appearing just days ahead of a courtroom showdown between Apple and the US Justice Department. The two sides are locked in an unprecedented fight over how far a tech company should go in helping with law enforcement investigations.

For Cook, the tempest, which burst into public view in February, has made things topsy-turvy.

"We're in this bizarre position where we're defending the civil liberties of the country against the government," Cook told Time. "The government should always be the one defending civil liberties, and yet there's a role reversal here."

It's all a bit eerie for the man who runs Apple. "I still feel like I'm in another world," he said, "that I'm in this bad dream."

Apple is battling with the the US government over the issue of iPhone encryption. The FBI has demanded that the company unlock an iPhone 5C tied to Syed Farook, one of the two shooters in the San Bernardino, California, massacre in December, in which 14 people were killed. The agency, which has a court order on its side, is pressing for Apple to create an new, custom version of its iOS software that would allow investigators to bypass the phone's lock screen.

The Cupertino, California, company, which had cooperated with the government up to that point, has staunchly refused, saying that its compliance would result in software, dubbed GovtOS, with a "backdoor" that would put all iPhones in jeopardy. Apple has called the government's request unconstitutional.

The government contends that the software would be specific just to the one iPhone in question and that Apple is putting its brand image ahead of the law.

The case has inflamed tensions over the larger conflict between individual privacy and national security. Apple and others believe that encryption, which secures data so it can be read only by those with authorized access, is vital to safeguard personal information and communications. The FBI and law enforcement officials say the technology blocks their ability to combat criminal and terrorist activity.

Cook believes the government should be promoting encryption rather than trying to force Apple to break it. If encryption were weakened for American companies as a result of a government fiat, then bad actors would simply turn to alternatives offered by non-American companies. Encryption is not simply an Apple thing, argues Cook, who adds that "some of the best encryption is funded by the government."

Apple did not immediately respond to a request for comment about the Time story.

The Justice Department and Apple will defend their positions in a hearing set for March 22 in federal court in Riverside, California. But Cook believes this is a matter best settled by Congress, and he's pushed for a commission that could examine the tangled and complex issues and come up with laws that make sense.

"We see that this is our moment to stand up and say, Stop and force a dialogue," Cook told Time. "There's been too many times that government is just so strong and so powerful and so loud that they really just limit or they don't hear the discourse."

Cook said that, in the end, "I'll follow the law" -- once there's an actual law that that would compel him to do what the feds are asking in this case. But does he worry that Congress or the courts will ultimately put the government's investigative powers ahead of personal privacy?

That would be "bad for America, really bad for America," Cook said. "And I don't expect it'll happen. I don't think it'll happen. There's too many bright people around."

The full article is available on Time's website.