SpaceX and Starlink are changing the night sky, and fast

Astronomers sound the alarm about Elon Musk's project, but the drive to launch thousands of broadband satellites is only accelerating.

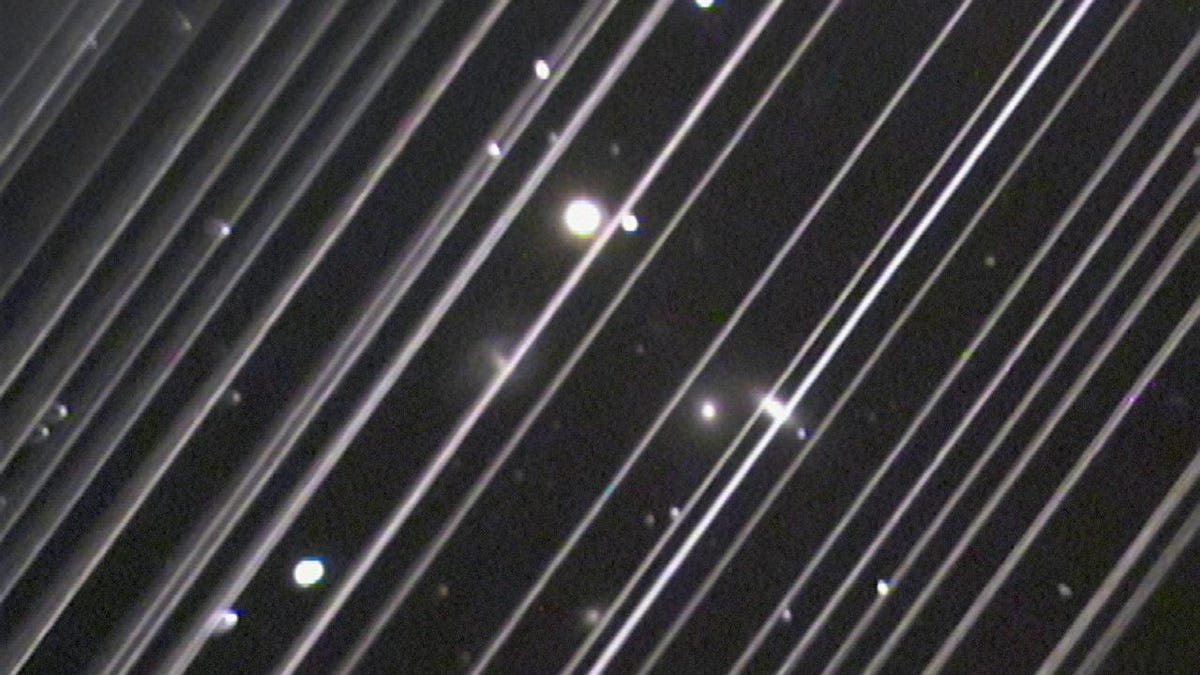

This image of a distant galaxy group from Arizona's Lowell Observatory is marred by diagonal lines from the trails of Starlink satellites shortly after their launch in May.

Astronomer Cees Bassa spends lots of time working with advanced radio telescopes aimed at deep space. But on May 24, 2019, he stepped outside near the Netherlands' famed Dwingeloo Radio Observatory and instead pointed a small video camera at the night sky.

It was more than sufficient to pick up a train of over 50 bright lights moving in formation. This was among the first recordings of the SpaceX Starlink constellation. The company had launched its first full batch of 60 broadband satellites less than 24 hours earlier.

SpaceX is looking to send thousands of satellites into low-Earth orbit with the goal of blanketing the planet with broadband internet access that anyone can connect to (for a price) from just about anywhere.

Bassa tweeted the video enthusiastically, calling it a "fantastic view" and "a must see."

But then he began to run the numbers. He calculated that once there are about 1,600 Starlink satellites in orbit, up to 15 of the bright lights will be visible for the majority of the night over much of Asia, North America and Europe during the summer.

"Even in the spring, autumn and winter, around half a dozen Starlink satellites will be visible at anytime up to three hours before sunrise and three hours after sunset. Depending on how bright they end up being, this will have a drastic impact on the character of the night sky," he wrote in May.

By the end of 2019, it became clear that the Starlink satellites are more reflective than either SpaceX or astronomers had expected.

"What caught everyone, principally, by surprise was the sheer brightness," Jeffrey C. Hall, of the Lowell Observatory, told reporters at a meeting of the American Astronomical Society in January.

Last night I observed two passes of the 60 @SpaceX #Starlink satellites. Though they are usually to faint to be seen with the naked eye, they flare regularly. In some cases, as this image shows, they can outshine the brightest stars in the night sky! pic.twitter.com/DDSdYMez2u

— Cees Bassa (@cgbassa) May 29, 2019

During the second pass (23:21 to 23:45UTC in the constellation of Lyra), I recorded raw video to get a better understanding of their behaviour. Here are a bunch of them; some of them flare to magnitude +4 or +5, while some stay around magnitude +6. pic.twitter.com/kAQsinw8jV

— Cees Bassa (@cgbassa) May 29, 2019

With SpaceX set to launch 60 more satellites Monday, there could be nearly 300 of the orbiting routers in the sky by next week. The company is aiming for nearly 1,600 by the end of 2020. And this is just the beginning.

SpaceX has the FCC 's thumbs-up to launch nearly 12,000 of the satellites in total and has filed paperwork with the International Telecommunication Union indicating it might like to launch 30,000 on top of that.

For a little context, it's estimated humanity has launched fewer than 9,000 satellites in total since the 1950s.

Bassa ran the numbers on the full-size FCC-approved Starlink constellation as well as smaller satellite fleets planned by OneWeb and Amazon. He found that the number of satellites visible in the night sky increases roughly in proportion to the overall size of the constellations. So if SpaceX recognizes the full scope of its ambitions for Starlink without figuring out how to make the satellites less bright, we can expect to see over 100 points of light flying across the night sky at almost any given moment.

The low inclination orbits of @amazon #Kuiper satellites means they'll be more visible at lower latitudes. These plots compare #STARLINK, #Kuiper and @OneWeb satellites for New York. Around 120 satellites would be visible during twilight above 30 deg elevation. pic.twitter.com/MaZK0CjY1S

— Cees Bassa (@cgbassa) October 19, 2019

More recent simulations have found that, even with 25,000 satellites in low-Earth orbit, the vast majority will be too faint to see with the naked eye, but a significant amount of uncertainty remains.

"The appearance of the pristine night sky, particularly when observed from dark sites, will nevertheless be altered, because the new satellites could be significantly brighter than existing orbiting man-made objects," the International Astronomical Union said in a Feb. 12 statement announcing the results of the simulations.

SpaceX didn't immediately respond to a series of questions for this story.

With Starlink satellites already marring astronomical observations at this very early stage, there's been an outcry from astronomers and a promise from SpaceX to work with scientists and remedy any of their concerns. An experimental "DarkSat" with a coating meant to make it less reflective was launched with one batch of Starlink satellites, but it's unclear if the approach can work.

The dark coating may cause the satellite to absorb more heat from the sun and ultimately malfunction. When Bassa attempted to observe the DarkSat in January, it didn't appear to be much fainter than its uncoated Starlink siblings. Other astrophotographers, including Thierry Legault, recorded similar observations in the video below. Bassa hopes to take another look soon to see what exactly is going on with the experimental satellite, but told me that weather has been uncooperative so far.

SpaceX has also been working on software that observatories can use to plan their astronomical observations in a way that avoids Starlink satellites.

"Some observatories, however, may not be equipped to use such a software program," the International Astronomical Union says in an FAQ on its website. "Also, when the number of satellites becomes too high, avoidance programs may not function as effectively as intended."

There are other concerns, too.

Managing an unprecedented amount of orbital traffic is a high-stakes game. A small number of accidental collisions could create scores of pieces of debris that then cause more collisions. In the worst case scenario, known as the Kessler Syndrome,

cascading collisions render orbit an inaccessible wasteland, cutting off access to space and our global telecommunications networks.

SpaceX and others have pledged to manage their satellite traffic responsibly and proactively, including going above and beyond what regulators require by de-orbiting satellites that are no longer operational so they burn up safely in the atmosphere.

But it didn't take long for Starlink to raise anxiety among other orbital operators. A Starlink satellite from the first batch launched in May came a little too close to a European Space Agency satellite in September, forcing the ESA to make a "collision avoidance maneuver" for the first time ever.

Constellations continue to grow

SpaceX has continued launching new batches of uncoated, highly reflective Starlink satellites every few weeks, and its competitor OneWeb is also ramping up its own satellite deployments. Despite the protests from astronomers, who have begun publishing open letters and circulating petitions, the space companies have strong incentives to keep rapidly increasing the size of their satellite constellations in the meantime.

On March 29, 2018, the FCC gave SpaceX the green light to launch the first phase of Starlink, comprising 4,425 satellites. But that permit comes with the requirement that half of those satellites are launched and operational within six years. That means SpaceX has to launch almost 2,000 more satellites in the next four years, or about 40 a month, presuming every satellite it launches reaches its operational orbit and works without incident.

This helps explain why SpaceX hasn't simply paused its launches while it figures out how to make its satellites less reflective. Presumably, there's also pressure to stay ahead of the competition, as rival OneWeb begins launching its own broadband constellation and Amazon's Project Kuiper is waiting in the wings.

There might also be a push to cash in on the coming 5G gold rush. While Starlink will sell retail internet access to customers using its own proprietary receiver like other satellite ISPs, Musk has suggested that Starlink could also sell wholesale internet access or "backhaul" to 5G network operators.

More recently, SpaceX COO Gwynne Shotwell has suggested that the company might be looking to spin off its Starlink business. SpaceX already has a sister company, SpaceX Services, that's been operating Starlink's ground stations, according to recent FCC filings.

"Right now, we are a private company, but Starlink is the right kind of business that we can go ahead and take public," Shotwell told a group of private investors last week, according to Bloomberg.

Building up the buzz for an eventual IPO is yet another reason the pace of Starlink launches isn't likely to slow down anytime soon.

The case for court

The tension between the rush to send thousands of satellites to orbit and the outcry over their unintended consequences has some suggesting the problem needs to be solved in the courts right away.

A trio of Italian astronomers, led by Stefano Gallozzi from the Astronomical Observatory of Rome, recently wrote an academic paper suggesting the US government could be sued by another nation in the International Court of Justice under the Outer Space Treaty of 1967.

The logic here is the treaty says each country is ultimately responsible for satellites launched by private entities based in their territory. Since SpaceX is an American company, the US government is technically accountable to the rest of the world for whatever SpaceX does in space.

However, suing the US government in The Hague would require the US to submit to the International Court's jurisdiction. Space law experts think that's highly unlikely.

"The chances of another state bringing the United States to the International Court of Justice is slim, much less suing under the Outer Space Treaty," says Michael Listner, an attorney specializing in space law and policy.

While it might be near impossible to bring the issue before an international court, Joanne Gabrynowicz, editor-in-chief emerita of the Journal of Space Law, says the Outer Space Treaty is still relevant to Starlink and other constellations that affect the work of astronomers.

"Article 9 of the Outer Space Treaty says that signatories must avoid harmful interference in the use of space by other signatories, so the question becomes how much light pollution constitutes harmful interference," she told me.

There is some precedent in US law for controlling commercial ventures that seek to change our view of space from the ground. One section of US code specifically bans "obtrusive space advertising," so it'd probably be inadvisable for SpaceX to start using images of its satellite trains moving across the sky in any Starlink marketing materials.

A new operating environment

There are other rumblings in the legal community about Starlink and its impact on how we receive starlight on Earth.

Ramon Ryan, a law student and incoming editor in chief of the Vanderbilt Journal of Entertainment and Tech Law, has researched the novel issue and thinks the FCC may have violated a federal environmental law in giving SpaceX the go-ahead to launch an unprecedented number of satellites. He lays out the argument in a lengthy paper, a draft of which he shared with me, that's set to be published in the journal this summer.

The FCC has operated under the assumption for years that commercial satellites have no adverse environmental impacts and are therefore categorically excluded from the detailed environmental reviews required by the National Environmental Policy Act.

Interestingly, NASA doesn't exclude its launches from environmental review, though it does streamline the process by using a single review to cover similar routine launches. Ryan suggests the FCC may be wise to adopt NASA's approach and consider the environmental impact of satellite constellations.

"A court would likely find that the FCC is required to review commercial satellite projects under [the National Environmental Policy Act] since these projects are likely to have direct, indirect and cumulative effects on the environment," Ryan writes.

"We strongly reject this theory," an FCC spokesperson told me. "The FCC's action in unanimously approving the SpaceX deployment was entirely lawful. The order provides ample legal rationale based on the public record -- which incidentally did not include any comments along the lines of these after-the-fact criticisms."

Nonetheless, Ryan suggests the FCC could complete an environmental assessment of commonly used satellite components. Satellite operators could then design their constellations to pass this boilerplate assessment and thereby avoid conducting a potentially lengthy review of their specific project.

"By doing so, the FCC would create standards in the commercial satellite industry that promote economic growth and stability while complying with Congress' mandate to the federal government to proactively consider the environmental impacts of its actions," Ryan concludes.

By the end of 2020 pictures of the aurora without #starlink satellite trails will be a thing of the past. #nightskyemergency #notostarlink #stopstarlink #planetaryemergency pic.twitter.com/xB5YjRs4wc

— Ian Griffin (@iangriffin) January 30, 2020

As it stands right now, no such legal challenges to Starlink or other competing satellite constellations have been filed.

SpaceX has followed the letter of the law in getting Starlink off the ground, according to the FCC, Listner and other legal experts. The company has also been working with groups of astronomers to address their concerns despite having no legal obligation to do so.

Some astronomers even argue that Starlink's promise of broadband internet access for almost any location may be worth the cost to science.

"We have a choice to either deny people the internet ... in the process denying them educational, financial, and other opportunities (or) make it easier for people to do ground-based astronomy," writes astronomer Pamela Gay. "Yes, the sky will be full of satellites, but which is the greater good?"

It's a debate that's likely to continue for many months and years to come.