Senators prepare to vote on Netflix and e-mail privacy

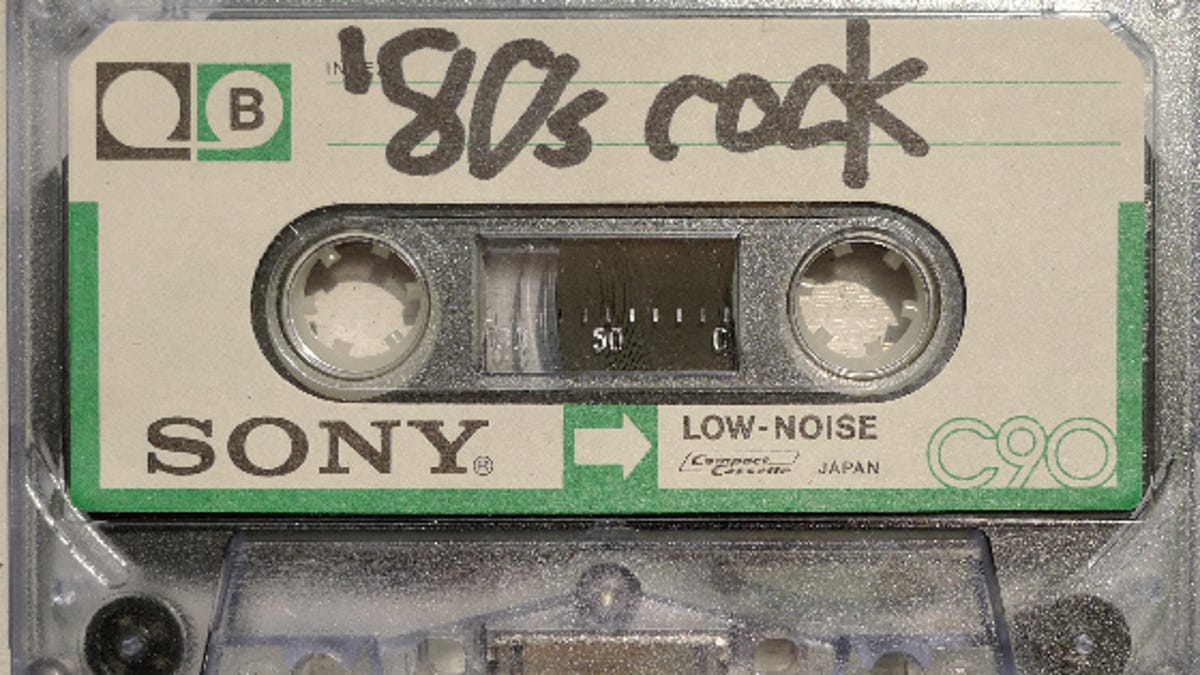

<b>news analysis</b> Privacy laws written during the era of big hair and the black-and-white Macintosh SE are set to be updated. But wouldn't it be better still not to enact technology-specific laws at all?

In 1988, when President Reagan signed a video privacy bill into law, computer users were sipping bandwidth through the tiny straws of 2400 bps modems, IBM was selling mainframe databases for over $200,000, and musician Rick Astley's "Never Gonna Give You Up" was topping the charts.

Well, it turns out that politicians are no better at prognostication than the rest of us are. The clutch of lawyers and their aides on Capitol Hill failed to anticipate the rise of Netflix and Facebook, and their well-intentioned but brittle video privacy law is now at odds with modern technology.

A U.S. Senate committee is meeting today to fix this. They're considering a bill, already approved by the House of Representatives, that would update the 24-year-old Video Privacy Protection Act to usher it into the era of cloud computing and social networks.

Here's the problem: At the moment, Netflix users in every country other than the United States have the option of configuring their accounts to automatically share what they're watching on Facebook. But because of a law enacted before Tim Berners-Lee even invented the World Wide Web, anyone living in the land of the free is barred from making that choice.

"We've had very positive discussions" on Capitol Hill, Christopher Libertelli, Netflix's head of global public policy, told CNET yesterday. "We're cautiously optimistic that those kind of changes will generate support."

The proposed fix, H.R. 2471, updates federal law to say that video rental companies may disclose personally identifiable information about customers subject to "informed" written consent, "including through an electronic means using the Internet." That consent can take place when a disclosure happens, such as when a Facebook post is being made, or "in advance for a set period of time or until consent is withdrawn by such consumer."

All this is proving to be a cautionary tale about the dangers of technology-specific laws -- the 1988 legislation actually mentions "video cassette tapes" -- and the limits of political competence when drafting them. Common-sense general laws restricting fraud or false advertising stay relevant for decades; a privacy law targeting cookies, which Europe recently adopted, is likely to be obsolete by the time it's enacted.

The VPPA was hardly a model of careful politicking. It was rushed through Congress by politicians panicked after a local newspaper disclosed the (rather tame) video rental records of Supreme Court nominee Robert Bork. The VPPA cleared the House in five days without a single hearing, and a Senate report was not filed until after the bill had already been sent to the president for his signature.

The surprising thing is that some privacy activists are opposed to updating the VPPA. In testimony (PDF) to a Senate committee, Marc Rotenberg, head of the Electronic Privacy Information Center said that Netflix users should not be allowed to consent to such disclosure: "acquiescing to a one-time blanket consent to cover future video choices is not meaningful consent."

"How do you consent to the disclosure of your information if you don't know which of your information will be disclosed, to whom it will be disclosed, or for what purpose?" Rotenberg added in e-mail yesterday.

On the other hand, nobody's forcing Netflix users to link their account with Facebook. They're not required to. The question is whether they'll be given the choice. (Justin Brookman from the Center for Democracy and Technology says "this bill does not pose a threat to consumers' privacy interests.")

"The fact that even after the proposed amendment, the VPPA will still use the archaic term 'video tape service provider' is emblematic of what's wrong with the law: The VPPA focused on one technology (and) one perceived privacy problem," says Berin Szoka, head of the TechFreedom free-market think tank. "No one imagined we'd ever live in a world where users would want to share what they were watching with their friends."

More to the point, perhaps, Netflix had 3.6 million streaming customers outside the U.S. Each already has the option to share video viewing habits on Facebook. No privacy Armageddon has erupted so far.

And here's another creaky old privacy law

The VPPA isn't the only law written in the 1980s -- when broadband services were a mere pipe dream -- that's scheduled to be rewritten tomorrow. The other is an amendment to the 1986 Electronic Communications Privacy Act, which Sen. Patrick Leahy (D-Vt.) has glued onto the VPPA fix.

If enacted, Leahy's ECPA fix will require federal, state, and local police to obtain a search warrant before accessing files stored in the cloud, including e-mail, which echoes a 2010 privacy ruling from a federal appeals court.

A coalition of Silicon Valley companies and liberal, conservative, and libertarian advocacy groups have been lobbying for nearly two and a half years to update ECPA, with little to show for it so far. Leahy's standalone bill has attracted precisely zero co-sponsors, and doesn't go nearly as far as the coalition had hoped. (Corporate members include Amazon.com, Apple, AT&T, eBay, Google, Facebook, Intel, and Microsoft.)

Complicating the situation is that, as CNET reported last year, the Obama Justice Department opposes requiring search warrants for e-mail. James Baker, the associate deputy attorney general, warned Congress that requiring a warrant to obtain stored e-mail could have an "adverse impact" on criminal investigations.

Leahy's decision to combine two tangentially-related bills could backfire if the e-mail privacy sections alienate law-and-order Republicans who would rather side with police over civil liberties groups. The final House vote for the Netflix-backed VPPA rewrite was a comfortably bipartisan 303 to 116. Gluing the two proposals together will make today's scheduled committee vote much more divisive.

Update 11:15 a.m. PT: Here's our followup article on the Senate vote being delayed after law enforcement groups protest.