Scientists shine a light on irregular heart beats

Biomedical engineers out of Johns Hopkins and Stony Brook say gentle beams of light -- instead of electric jolts -- could be used to treat arrhythmias in the near future.

Irregular and sometimes life-threatening heart rhythms -- called arrhythmias -- are able to be treated thanks to electric jolts in defibrillators and pacemakers, but those jolts aren't completely without risk. Not only can they be painful, but in some instances they can even damage tissue.

And while most people would probably put up with a little pain if it means saving their lives, five biomedical engineers at Johns Hopkins and Stony Brook universities figured they'd work on improving the system to see if these devices would work just as well without the jolts of electricity.

Instead, they want to treat arrhythmia with light, the scientists said in an August 28 report in the journal Nature Communications.

The idea is to "reshape the behavior of the heart without blasting it," said project supervisor Natalia Trayanova, the Murray B. Sachs Professor of Biomedical Engineering at Johns Hopkins, in a school news release. She adds: "When we use a defibrillator, it's like blasting open a door because we don't have the key. It applies too much force and too little finesse. We want to control this treatment in a more intelligent way."

Trayanova and her team are working in the relatively new field of optogenetics, which involves inserting proteins that are sensitive to light (called "opsins") into cells. (Some of the early work in optogenetics involves controlling the bioelectric behavior of brain cells to understand and perhaps ultimately treat psychiatric disorders.)

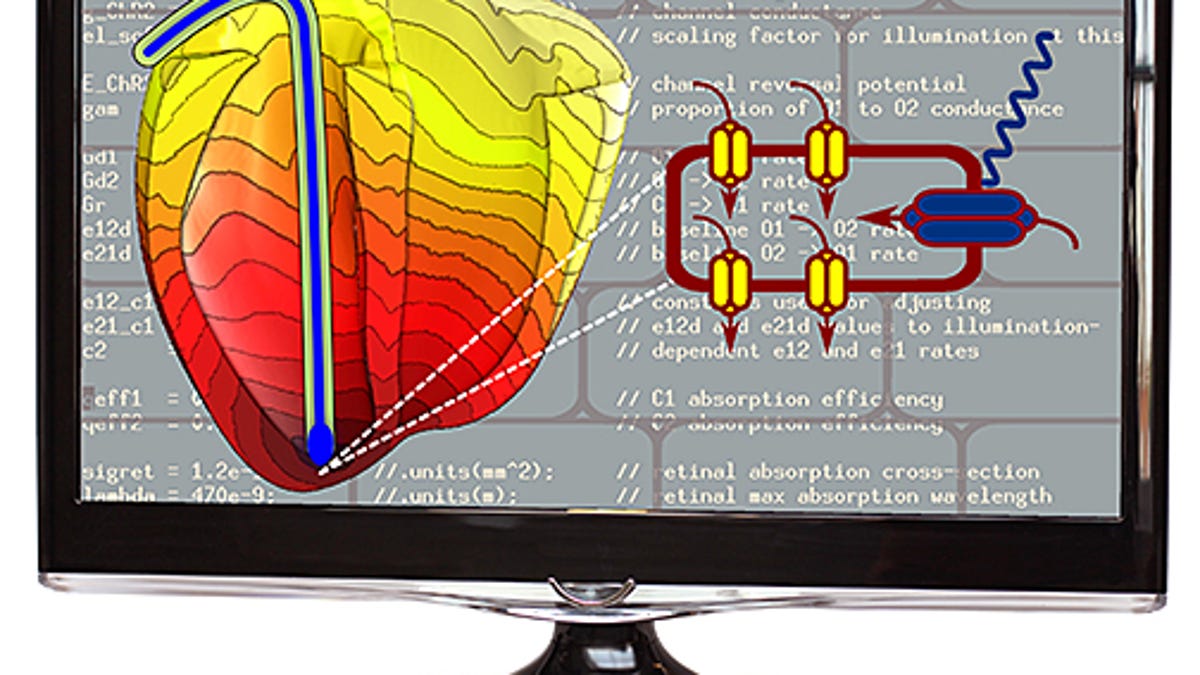

For her part, Trayanova has spent years working on extremely detailed computer models of the heart that can stimulate various behaviors within the heart, from the molecular level on up. In this study, she leaned on biological data gathered at the Stony Brook lab of Emilia Entcheva to inform her own computer model for restoring healthy heart rhythms with light. By inserting opsins into certain cardio cells, the team hopes to essentially make the heart light-sensitive and thus light-manipulable.

"One of the great things about using light is that it can be directed at very specific areas," Patrick M. Boyle, a postdoctoral fellow in Trayanova's lab and lead author of the Nature Communications paper, said in the news release. "It also involves very little energy. In many cases, it's less harmful and more efficient than electricity."

The researchers say that, because of Trayanova's computer model, it may take fewer than 10 years to conduct enough virtual experiments and gather all the information they need to replace electrical jolts with light. For now they are working on how to position and control the light-sensitive cells, as well as how much light is required to activate the process.

In a sense, Trayanova's work is completing a circle that began with Johns Hopkins researcher William B. Kouwenhoven, who developed the closed-chest electric cardiac defibrillator in the 1950s. Interesting, Kouwenhoven was a pipe-smoking electrical engineer without a medical background, but his creativity and connections with colleagues in medicine led to one of the greatest advancements in the cardio world to date, even if the tech did get its start as a 200-pound contraption on a wheeled cart.

If this latest experiment works, replacing electric blasts with specific doses of gentle beams of light would surely be the next step in giving the heart-healing tech more finesse.