Science finds fingerprints on Earth of distant exploding stars

New research finds prehistoric climate change and even a speeding of evolution on Earth could be blamed in part on the death of a (very) distant star.

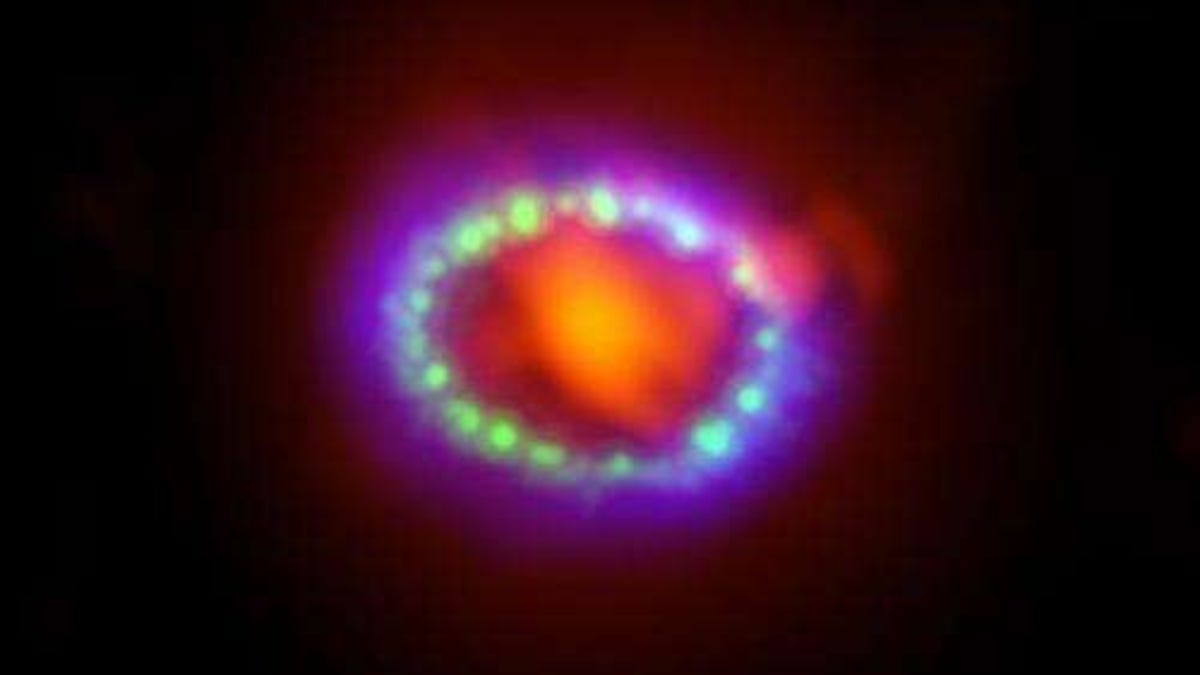

Twinkling stars seem like little more than individual pixels on the better-than-digital display that is the night sky. But when those distant suns die and send a supernova explosion tearing across the cosmos, the shock waves can sometimes be felt on Earth, new research has found.

In April, researchers presented evidence of a pair of prehistoric supernovas that exploded around 300 light-years from us. A new follow-up study based on computer models finds the resulting blast of radiation in the form of cosmic rays probably made it all the way to the surface of our planet, impacting our planet's atmosphere and living flora and fauna beneath it.

"I was expecting there to be very little effect at all," said Adrian Melott, professor at the University of Kansas, in a news release Monday. Melott is co-author of a paper outlining the findings in The Astrophysical Journal Letters. "The supernovae were pretty far way -- more than 300 light-years -- that's really not very close."

Melott says one of the stars likely exploded 1.7 million to 3.2 million years ago and the other went supernova 6.5 million to 8.7 million years ago. Both times, when the cosmic "wind" from the explosions reached our planet, the resulting blue light would have shined brightly in the night sky, disrupting animals' sleep for weeks.

Some grumpy insomniac mammoths roaming the ancient tundra would have been the least of it, though. The cosmic gust could have tripled the normal dose of radiation that plants and animals at the time were used to on the ground and in shallower waters.

Melott says the increase in irradiation may have been high enough to cause an uptick in the mutation rate and cancer, "but not enormously. Still, if you increased the mutation rate you might speed up evolution."

Could the pair of supernovas have led to the prehistoric equivalent of X-Men-style mutants with super abilities? Probably not. It may have been quite the opposite, really. Melott thinks a minor mass extinction that happened around 2.59 million years ago could have some connection to boosted cosmic rays that would have contributed to changes in climate and a significant increase in lightning strikes.

"There was climate change around this time," Melott said. "Africa dried out, and a lot of the forest turned into savanna. Around this time and afterwards, we started having glaciations -- ice ages -- over and over again, and it's not clear why that started to happen. It's controversial, but maybe cosmic rays had something to do with it."