Russia's Internet blacklist looms in freedom crackdown

The country's move to strengthen its "Internet blacklist" could lead to blockage of porn, drug-related, and "extremist" sites. Would it also threaten political protests?

The United States had SOPA, and Britain has the Digital Economy Act. China is -- well, in a league of its own.

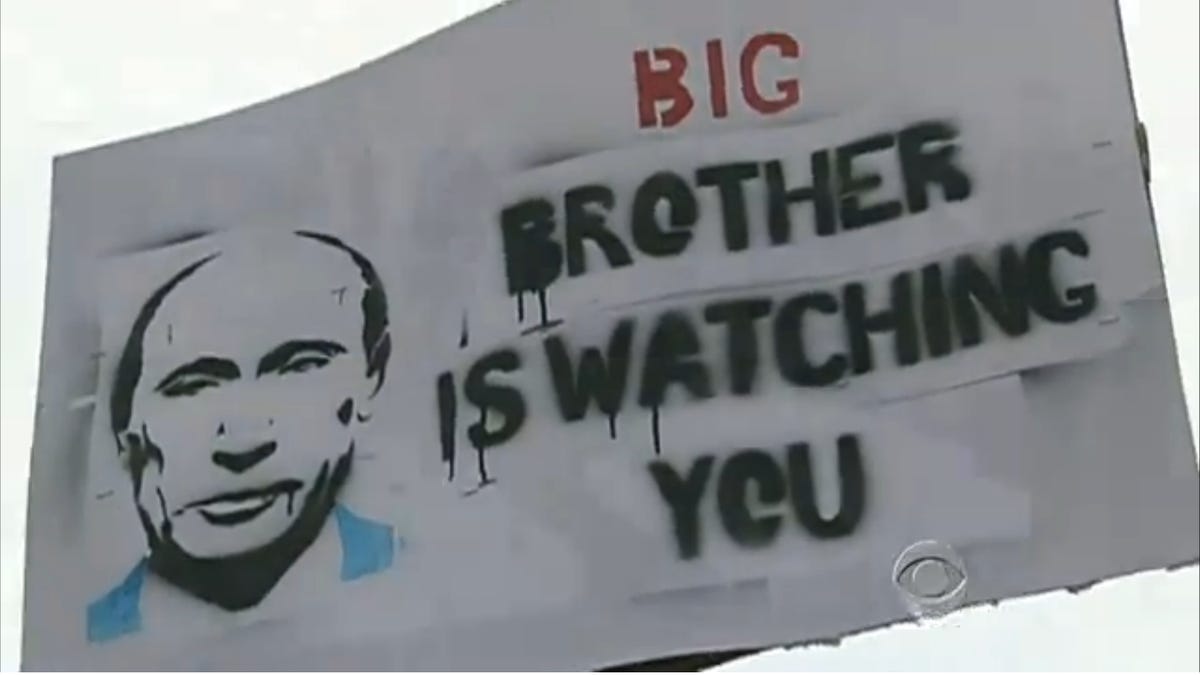

Russia is next on the list of developed nations pushing for widespread Web site blocking and censorship capabilities in the wake of an online uprising prior to the inauguration of Russian president Vladimir Putin. Thousands of protesters took to the streets, set up blogs, and disseminated demands for a fresh ballot over social networks following claims of a rigged votes and electoral corruption in the recent presidential elections.

Under the draft bill, all Web sites that contain pornography or drug references, or that promote suicide or other "extremist ideas," will face blacklisting, Russian legislators said yesterday, according to news agency Ria Novosti.

In a rare show of cross-party support, all four political factions in the state parliament have contributed to the draft bill that would amend existing laws to solidify the blacklist into law.

Any Web site that falls foul of Russian law faces an immediate notification and adding to the blacklist within 24 hours if the content is not removed.

The fast-tracked bill --- aptly named the "provoking children to act in ways which are harmful to themselves and their health and development" bill --- has not seen a public consultation.

Historically, bills introduced to any country's congress, parliament, duma, or legislative branch that include the word "children" in the title often end up inciting measures that would impede how ordinary citizens access the Web. (Consider, for instance, the battle in the U.S. in the decade gone by over COPA, the Child Online Protection Act..)

Russia's federal communications regulator, Roskomnadzor, will supervise the blacklist and have the authority to add sites that fall foul of the law. A non-profit organization will be appointed to monitor Web sites' compliance with takedown requests.

The courts will also have the power to deem sites as inappropriate for the general public or in breach of Russian law, particularly sites that incite or advocate violence, and can also have sites added to the blacklist.

And Russia's infamous security and intelligence services would also be able to add "infringing" sites to the list, according to Ilya Kostunov, deputy of the United Russia party currently in government, as cited in London's Financial Times.

Internet providers would be forced to install "black box" equipment enabling the government to block sites. The cost of the system is pegged anywhere between $50 million and $10 billion, and would give the Kremlin further powers to monitor and control the Russian Internet at the request of Russia's security and intelligence services.

A human rights watchdog set up by the Kremlin described the blacklist "real censorship" of the Internet. The Human Rights Council went on to call for a halt to the bill's implementation, warning that the benchmark of what could be considered harmful to the public "could easily be expanded."

The proposed measures would also put additional financial burdens on Internet providers, and would "negatively affect [the Russian-speaking Internet's] speed, stability and security," the watchdog warned.

Russia has a population of about 145 million, just under half of whom -- around 66 million -- use the Web every day, according to Russian journalist Ksenia Sobchak, who was once described as a "stiletto" in President Putin's side.

The system is not new, however. The Justice Ministry already operates a blacklist of "law-infringing" Web sites and materials banned by the judiciary, including offline publications, leaflets, and even, in some cases, music. The list stands at just shy of 1,200 entries.

But the criteria were not specified. The bill doesn't specify enforcement or even implementation. What's more, definitions of "porn" and "extremist ideas" are not defined. The law gives the Russian government and the judiciary the tools to govern and enforce morality and control political speech, raising fears that its reach also could extend into business and anticompetitive blacklisting.

Passage of the bill may also make it harder for critics of the Russian government's policies and practices to make their case online as Web sites that promote freedom of speech in Russia could be seen as "extremist" material and face a near-immediate Web site block.

In two recent cases, again reported by the Financial Times, one prominent .ru website was recently shut down by order of Moscow city prosecutors. Compromat.ru, a site that publishes reports of corruption, was forced to change its domain to a U.S.-owned .net address following the suspension of its .ru address.

Vedomosti.ru, a Moscow-based newspaper, also lost its .ru domain after a court ruling, following accusations that it printed "unchecked information." The complaint originated from the Putin administration.

A first reading of the bill was expected for today.