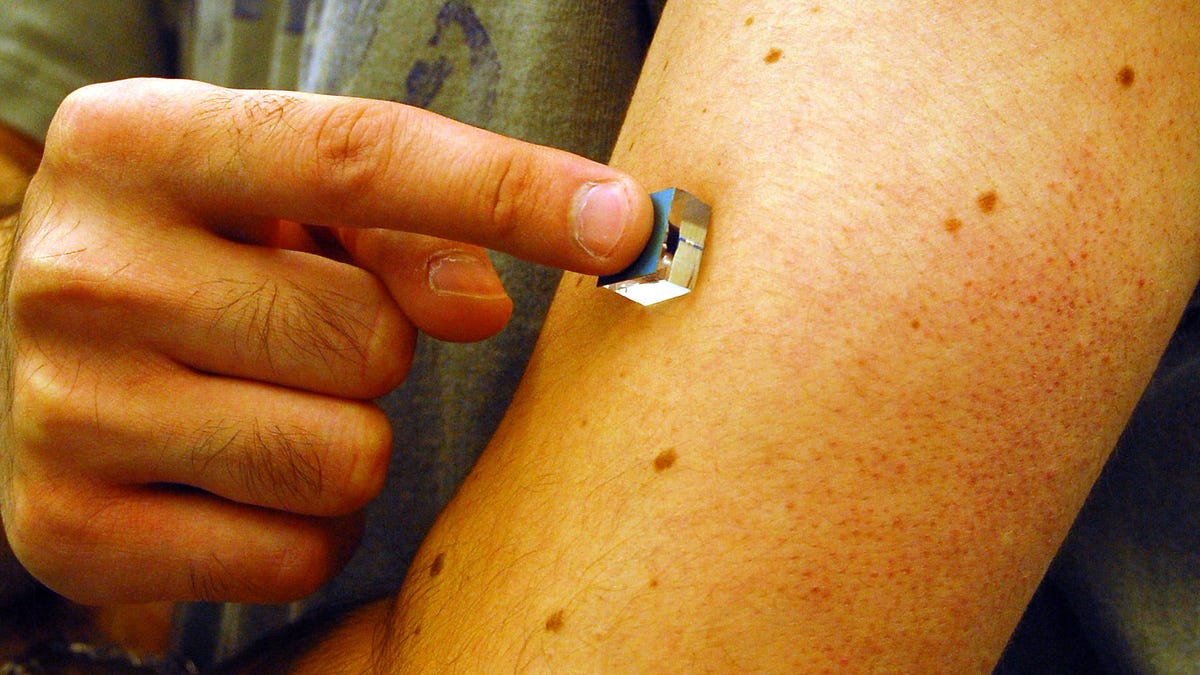

New pump to deliver drugs via microneedle patch

Researchers at Purdue University develop a pump that, activated by body temperature alone, could push large-molecule drugs through painless microneedles.

We've written about microneedles before. For the past few years, researchers at the Georgia Institute of Technology have been working on a patch of tiny needles that can deliver drugs painlessly and easily.

But the molecules of many drugs are too large to be delivered transdermally (through the skin), which is how conventional patches work, and would not fit through these newer microneedles.

Researchers at Purdue University, however, have developed a new type of pump that should exert enough force to squeeze drugs through microneedle patches, thereby reducing the need (at least in some instances) for injection via those old-tech, scary hypodermic needles.

The pump holds both the drug and a liquid (contained separately in a pouch) that boils at body temperature; the resulting vapor exerts enough pressure to force the drug through the 20-micron-wide needles. In other words, the heat of one's finger is all that's required to activate the pump.

"We have developed a simple pump that's activated by touch from the heat of your finger and requires no battery," said Babak Ziaie, a professor of electrical and computer engineering, as well as biomedical engineering, at Purdue. "It takes 20 to 30 seconds [and is] like a bandage--you would use it and discard."

The solution, while simple and elegant, solves a truly complex problem: generating enough force--"a few pounds per square inch," Ziaie says--from such a miniature pump.

Ziaie's team tested prototypes using fluorocarbons. Future research will likely include pairing the pump with microneedles to get a better sense of which drugs work and how.

Ziaie, alongside electrical- and computer-engineering doctoral students Charilaos Mousoulis and Manuel Ochoa, respectively, plan to present their findings in a paper at the 14th International Conference on Miniaturized Systems for Chemistry and Life Sciences in early October at the University of Groningen in the Netherlands.

They say they've already filed an application for a provisional patent on the pump.