NASA finds space rock Ultima Thule is two bodies in an eternal hug

New Horizons' visit to the cold, tiny world provides a glimpse at the earliest days of our solar system.

Travel far enough toward the edge of the solar system and it's as if you've traveled back in time. That's what NASA's New Horizons spacecraft found when it passed beyond Pluto deep into the Kuiper Belt to perform a flyby of an object nicknamed Ultima Thule.

Kuiper Belt Objects orbit the sun so far out they may wander in the frigid void for billions of years undisturbed and therefore unchanged since the solar system formed. To visit one is to see our corner of the cosmos as it looked over 4 billion years ago.

New Horizons performed its flyby of Ultima Thule, officially known as 2014 MU69, on New Year's Day. Researchers have just published the initial results from the spacecraft's observations of the distant object.

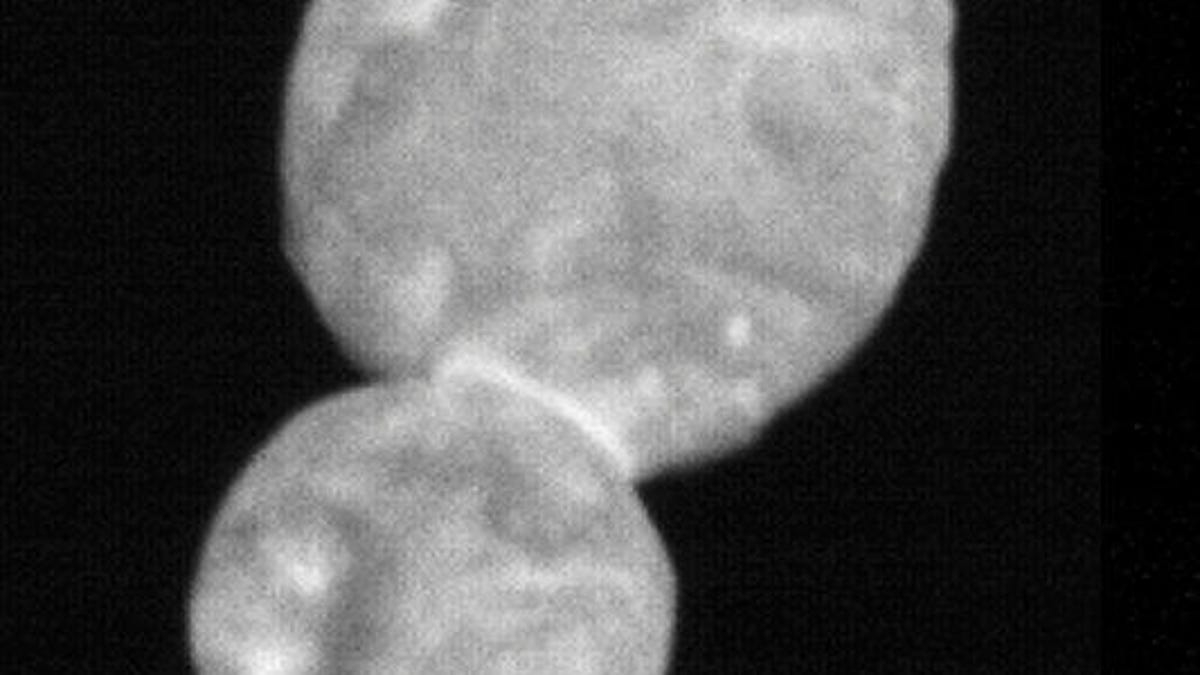

The paper, published in Friday's edition of Science, describes a space rock shaped like a flattened snowman drifting alone in the cold. Ultima Thule has no apparent satellites, rings or even detectable amounts of dust and gases accompanying it as it makes its 293-year journey around the sun.

Earth's origin story is one of violent collisions. It's thought that our planet's earliest days were marked by a heavy bombardment of asteroids, comets and other leftover bits from the solar system's formation. The moon itself may even be a product of a massive early collision.

But out in the far reaches of the Kuiper Belt, where the sun's radiation is barely felt as either light or warmth, Ultima Thule seems to have had a remarkably peaceful history. Even the joining of the object's two lobes (the larger "belly" of the snowman shape is called Ultima while the head is Thule) was not the result of a violent impact.

"All available evidence indicates that MU69 is instead the product of a gentle collision or merger of two independently formed bodies, possibly contacting one another at (or more slowly than) their mutual gravitational infall speed," reads the paper by lead author and New Horizons chief Alan Stern, along with dozens of credited co-authors.

In other words, Ultima Thule is two smaller bodies in a sort of eternal hug, clinging to each other in the cold darkness for billions of years. This coming together was a relatively calm event, and perhaps the only event Ultima Thule has ever experienced, at least until a strange robot flew by it a few months ago on a sightseeing expedition.

Before visiting Ultima Thule, New Horizons explored Pluto's planetary system in 2015, sending back vivid and detailed images of a surprisingly complex world.

In addition to discerning some of Ultima Thule's origin story, NASA's spacecraft helped confirm that the smallish world (30 kilometers or 19 miles wide) is red in color as expected, but comes with some unexpected and so far unexplained bright spots.

This is likely just the beginning of what New Horizons will teach us about Ultima Thule, the Kuiper Belt and the origins of our solar system. Stern and colleagues write that this study is based on only about 10% of the total data New Horizons gathered during its January flyby.

More data will continue to come in until transmission is complete in 2020.