Microsoft security--you've come a long way, baby

Microsoft products are much more secure than they were 10 years ago, security experts say.

Ten years ago, Microsoft had a big problem. Buggy code was allowing viruses like "CodeRed," "ILoveYou," and "Nimda" to infect millions of computers running its Windows and Microsoft's Web server software.

Times have changed.

Back then, the steady stream of worm outbreaks, coding glitches that annoyed users, and security weaknesses reported by outside researchers was having a steady and negative effect on the company's reputation. Microsoft was everywhere on consumer and corporate PCs worldwide, but the software giant couldn't seem to deliver solid software.

Then came a famous Bill Gates memo on January 15, 2002, that promised to change all that. Gates realized that if the company didn't get its security act together the future of its .Net framework for network services, and the company itself, would be threatened. His company-wide e-mail warned:

As software has become ever more complex, interdependent and interconnected, our reputation as a company has in turn become more vulnerable. Flaws in a single Microsoft product, service or policy not only affect the quality of our platform and services overall, but also our customers' view of us as a company.

So now, when we face a choice between adding features and resolving security issues, we need to choose security. Our products should emphasize security right out of the box, and we must constantly refine and improve that security as threats evolve.

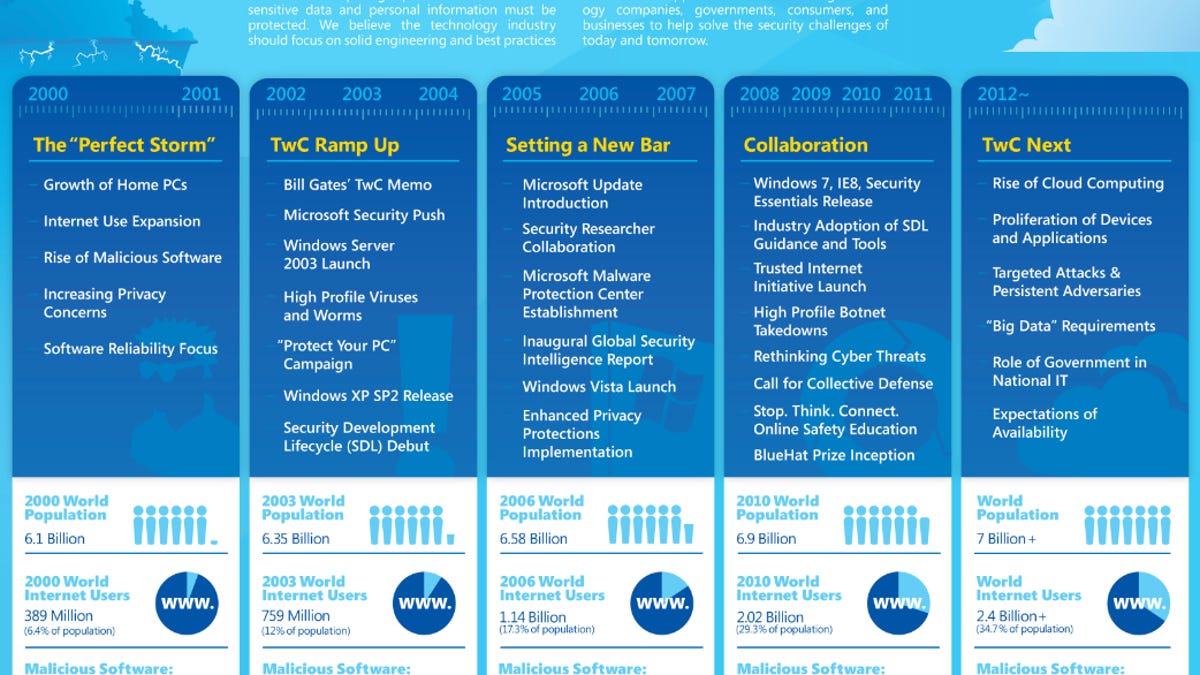

To solve the crisis, the company embarked on a new Trustworthy Computing initiative, which Gates said "is the highest priority for all the work we are doing. We must lead the industry to a whole new level of Trustworthiness in computing."

At the time, security expert Richard Forno cynically told CNET that his gut feeling was that Gates' e-mail was "a PR blitz, pure and simple."

Ten years later, his view has certainly changed.

"They fixed parts of Outlook we complained about, and even overcompensated with Windows Vista and the [User Account Control warnings] annoyances there in the name of security," Forno said. "For simple user tasks, such as changing the desktop color, you had to click through an alert, confirm the action or type in your password."

However, the UAC warnings failed to be effective when people chose to ignore them and just clicked through, so Microsoft toned them down in Windows 7.

"On the whole, they're much improved now than they were then" on security, said Forno, graduate program director for cyber security at the University of Maryland in Baltimore County.

Other security experts concur.

"I agree that their products have gotten a lot better. How insecure they still are says a lot about how hard this problem really is," Bruce Schneier, chief security technology officer of BT, said in a backhanded compliment.

"They've turned the ship several degrees towards security, for sure," said Gary McGraw, chief technology officer at consulting firm Cigital. "They are by far the leaders in software security."

Birth of a movement

"They went from being one of the worst companies in security to being one of the best," said Marc Maiffret, founder and chief technology officer at eEye Inc. who was a prominent critic of the pre-Trustworthy Computing Microsoft.

At the young age of 21, Maiffret discovered Code Red, the first worm to target a Microsoft platform. He and other hackers were thorns in Microsoft's side, constantly banging on its software to uncover holes and releasing exploits to prompt the company to fix the weaknesses more quickly. After Code Red, Maiffret testified before Congress about the worm menace that was affecting Microsoft customers.

"People were upset [about the security problems] but didn't know how to channel their anger and frustration," largely because Microsoft was the main game in town, he said. "Two weeks leading up to Code Red, peoples' Web servers were crashing and they didn't know why. The worm was spreading and infecting computers and the industry was ignorant to what was going on."

When the Gates memo came out, security researchers were thrilled that finally the company was going to start taking security seriously, according to Maiffret. "Finally, there was a breakthrough," he said. "It was the right place at the right time, the birth of a movement."

From that moment on, Microsoft made security a part of the process of building its software, rather than trying to include it as an after-thought. It was a cultural change and it affected every product and technology engineers worked on. Two technologies in particular have boosted the protection of customers--address space layout randomization (ASLR) and data execution prevention (DEP).

Meanwhile, the lion's share of vulnerabilities have shifted from Microsoft software to Web applications, in part because of Microsoft's security efforts and in part because that's where the user activity is nowadays. Many Web application developers don't know to build software with security in mind, like veteran Microsoft does.

Microsoft also is sharing what it has learned and its tools with other companies, particularly its partners whose security vulnerabilities bleed over into its software and customers. Microsoft offer free downloads of its Security Development Lifecycle (SDL) Optimization Model and its SDL Threat Modeling Tool. In addition, Adobe -- whose security problems are reminiscent of Microsoft's circa 2002 -- is borrowing some of Microsoft's solutions, such as regular security updates and sharing information on vulnerabilities with vendors ahead of the release of updates so they can fix their software.

"Microsoft put a lot of investment into building the Security Development Lifecycle and learned many lessons along the way on what worked well," said Brad Arkin, senior director, security, Adobe products and services. "In formalizing our own secure product lifecycle, we were eager to tap into that knowledge instead of reinventing the wheel. This allowed us to spend more time on the actual implementation across all of our product teams."

"The industry looks up to Microsoft, especially from a secure coding perspective," said Nitesh Dhanjani, an executive director at Ernst & Young. "I've had clients tell me they draw inspiration from that. They've seen results in the sense that fixing bugs earlier in the lifecycle is worth the effort by saving money and protecting data."

Rather than view security researchers as the enemy, Microsoft embraces them as the valuable partners they can be. The company invites researchers to speak at a Blue Hat conference it hosts annually on its campus and brief engineers on different hacking techniques, said Jeff Jones, director of Trustworthy Security at Microsoft. And the company announced at the Black Hat conference last summer a new $250,000 Blue Hat prize for the best example of security defense research. The company also has been aggressive using technology and innovative legal means to takedown botnets.

Microsoft isn't resting on its laurels, though, and affirming its commitment to security in another company-wide e-mail today.

"'TwC Next,' the ensuing decade-plus of Trustworthy Computing, will focus on the new world of devices and services," wrote Craig Mundie, chief research and strategy officer at Microsoft. "Everyone at Microsoft and the entire computing ecosystem has a role to play."

"We are equally committed to taking lessons learned and this foundation we've built and applying it to computing going forward for the next 10 years," Jones said.

In a world where smartphones and social networking dominate people's lives, Microsoft will work to provide secure software regardless of the application or device.

"There is a dependency on computing that didn't exist 10 years ago," Jones said. "We've learned...that trust of our customers is the greatest asset a company can have."

The Gates security e-mail changed the entire software industry, Forno said.

"The Trustworthy Computing thrust by a major vendor brought security into the forefront of the public eye," he said in an interview. "That is probably the lasting outcome. That memo 10 years ago raised the level of awareness about security in computing to the Internet security community at large."

Updated 9:56 a.m. PT with Craig Mundie e-mail.