Microbes may be to thank for BP oil spill cleanup

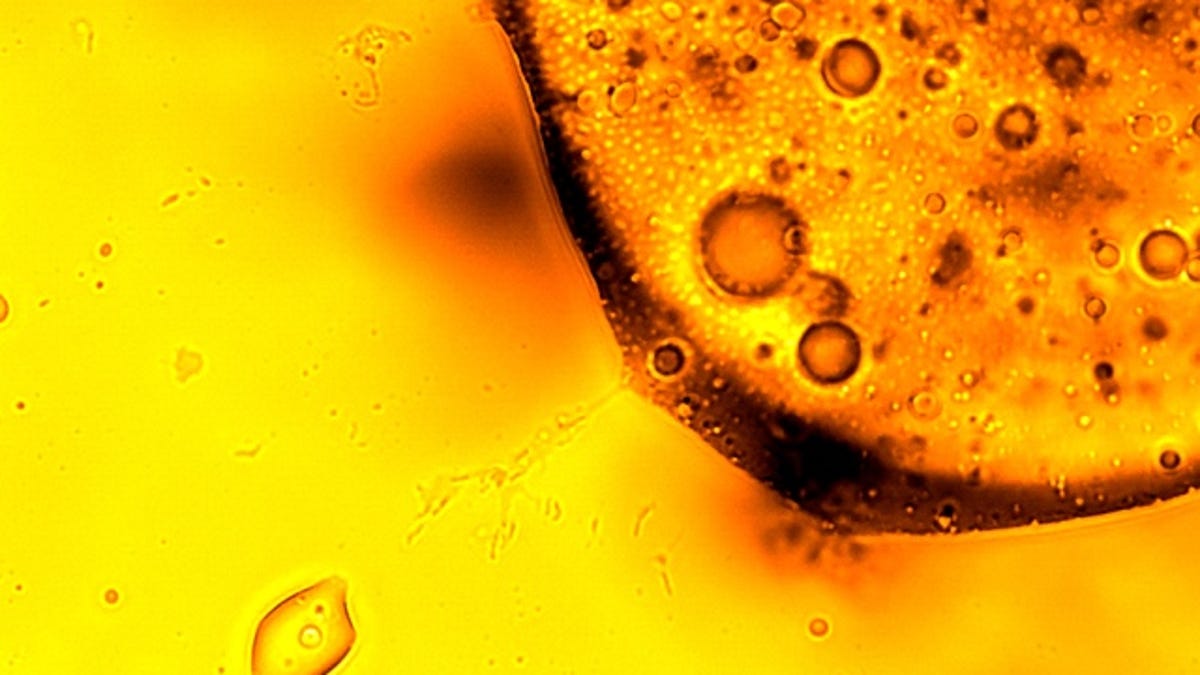

Berkeley Lab scientists using PhyloChip analysis say a previously undiscovered species of ocean microbe is aggressively gobbling oil plumes from the Gulf of Mexico oil spill.

Humans may have naturally occurring nanotechnology to thank for partially cleaning up the oil spill from BP's Deepwater Horizon rig.

Researchers from Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory have found that previously undiscovered ocean floor microbes have literally risen to the occasion and begun degrading the giant underwater oil plume in the Gulf of Mexico.

While there was belief that some ocean microbes might aid in the degradation of the oil spill, the process has happened more aggressively than anyone predicted it would, according to a report from environmental biotechnologists at the Berkeley Lab.

One of the giant oil plumes that formed due to the oil spill has been degraded at a much more significant rate than first anticipated. The change is attributed to a previously undiscovered species believed to normally reside at the bottom of deep ocean waters, but catalyzed to multiply by the ocean's pollution.

"Our findings show that the influx of oil profoundly altered the microbial community by significantly stimulating deep-sea psychrophilic (cold temperature) gamma-proteobacteria that are closely related to known petroleum-degrading microbes," said Terry Hazen, a microbial ecologist who is leader of the Ecology Department and Center for Environmental Biotechnology at Berkeley Lab's Earth Sciences Division and the principal investigator with the Energy Biosciences Institute.

"This enrichment of psychrophilic petroleum degraders with their rapid oil biodegradation rates appears to be one of the major mechanisms behind the rapid decline of the deepwater dispersed oil plume that has been observed," Hazen said.

The study included the analysis of 200 ocean samples collected from 17 deepwater sites between May 25 and June 2. Hazen and his team used the award-winning Berkeley Lab PhyloChip, a DNA-based microarray the size of a credit card, to analyze the ocean samples.

The PhyloChip has been lauded for its breakthrough ability to "detect the presence of up to 50,000 different species of bacteria and archaea in a single sample from any environmental source, without the need of culturing." Previous to the PhyloChip's invention, scientists had to rely on taking bacterial cultures in order to identify microbes in air or water, a process in which 99 percent of the bacteria in a sample often don't survive, according to the LBNL.

It was through the use of the PhyloChip that Hazen and his team determined that a new species of microbe, one the group says is akin to Oleispirea antarctica and Oceaniserpentilla haliotis, is the dominant microbe responsible for the cleanup.

There is some other good news.

A drastic depletion of oxygen in the ocean, due to microbes' natural process of extracting oxygen from ocean water as it feeds, has been another concern among scientists, with regard to the BP oil spill. But Hazen's group did not detect a drastic drop in oxygen levels in the seawater samples they studied.

The report from the study, "Deep-sea Oil Plume Enriches Indigenous Oil-degrading Bacteria," will be published online in the August 26 edition of the journal Science.