Muslims seek safe haven in Tutlub social network

Are you a Muslim looking to escape online harassment and discuss your religion stigma-free? There's a site for you.

If you're active on the Internet, chances are you've posted something that was later taken out of context. It is, after all, the Internet, where jumping to conclusions is the norm.

But what if the innocuous comment you make online leads someone -- a stranger or, worse, a person you know -- to accuse you of being a terrorist?

That's the risk that Muslims face, many of whom find it difficult to talk about their faith online due to fear of retribution. It's exactly these kinds of experiences, both "misinterpretations and stigmatizations," that led Yusuf Hassan, a Nigerian tech entrepreneur based in the UK, to create Tutlub. The site is a social network designed to serve as a haven for Muslims.

The emergence of Tutlub comes amid a recent tide of backlash against Muslims following the Syrian refugee crisis and last year's terrorist attacks in Paris and California. Republican presidential frontrunner Donald Trump has even suggested that the US ban Muslims from entering the country. It has gotten so bad that Facebook last month set up a European program to thwart xenophobia that followed CEO Mark Zuckerberg's proclamation that Muslims would always be welcome on his social network.

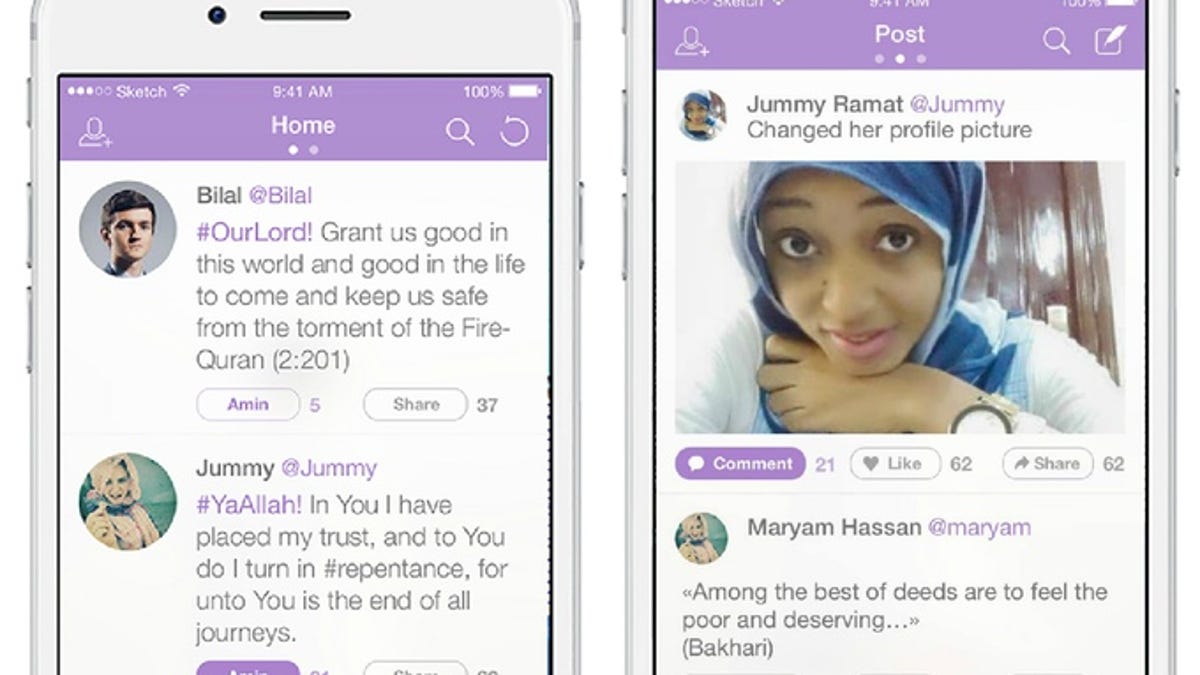

Tutlub, which means "to ask" in Arabic, stands in contrast to the fear that social networks have become recruitment tools for extremist groups such as ISIS. Instead, the social network is a place for Muslims to discuss their faith, seek guidance and read curated content. Hassan also wants the site to monitor and counter the spread of propaganda.

"This will show true modern values of Islam and support Muslim individuals at risk of misinformation by extremist groups," Hassan said in an interview last month.

Tutlub is in early trials with volunteers but became a top 20 trending social app on Google Play in Nigeria within two weeks of launching there, according to App Annie. Hassan is hoping Tutlub will appeal to emerging Internet users in countries with large Muslim populations like Nigeria, India and Indonesia. It will be available on the web and in the Google Play store as a free app.

While other Muslim social networks have failed to take hold in the past, Hassan believes his timing is right with the rise of online access in countries like his native Nigeria, where there is no allegiance to any particular Internet service. He doesn't envision Tutlub replacing Facebook but instead to serve as a complementary network free from judgment.

"Employers nowadays do check potential employees' Facebook page and a Muslim candidate with a page full of Islamic content might be misconstrued," said Hassan. His own experiences of using social media as a Nigerian based in the UK have made him "cautious."

Vetted guidance

Tutlub is Arabic for "to ask."

Tutlub will be overseen by clerics and community leaders. "By so doing we will be helping in our own way to solve the problem of indoctrination through social network by providing moderate, vetted and verified Muslim leaders for users to ask questions," Hassan said.

It is a space to pray, to seek religious guidance and to read curated Islamic content from media sources and scholars.Articles will come from many sources, the idea being that the social network should actively draw users to read and engage in meaningful discussions about the Muslim faith. Examples given in screenshots on Google Play include "A Muslim woman makes history at law school" and "The 10 oldest mosques around the world."

Tutlub gives people a profile to present themselves with a photograph and a short bio, underneath which will be their prayers and posts. Just as with every other social network you use, the crux of it all is a home feed. This is where people will see prayers -- and only prayers -- from those they follow. Instead of responding with a thumbs up a la Facebook or a heart as you would on Twitter, you can click "Amin" to add your own "Amen" to someone else's prayer.

A separate, less central feed will allow people to pose questions to other users and Muslim leaders, anonymously if they choose, in order to receive guidance. Hassan has strong links with respected Islamic scholars and clerics in Nigeria, he said, and he has enlisted their help to ensure the network accommodates differences in levels of faith and practice. The aim is to focus on what makes Muslims similar, rather than what divides them.

Not about isolation

Tutlub could be interpreted as a move to segregate Muslims from non-Muslims and, in doing so, further aggravate existing problems. But Hassan is clear that non-Muslims curious about Islam are welcome on the social network. It is not designed to be exclusionary.

"Isolation is not something we aim at, nor do we advise," he said.

Conversely, he encourages Muslims to embrace mainstream networks as well. He's active on Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn, places to interact with friends with other religions and backgrounds.

"People should be free to socialize with a diverse set of people as well as be free to socialize with the close circle of people that share the same faith with them," Hassan said.

It's the discussion of faith that tends to be touchy. Ignorance, paranoia and stereotyping can prevent non-Muslims from distinguishing between religious devotion and extremist inclinations.

It's clear why they would be sensitive. Tell Mama, an organization that supports victims of Islamophobic attacks, found more than 110 anti-Muslim hate incidents in the five days after the Paris attacks in November. The US Council on American-Islamic relations reported a similar spike, which they described as an "unprecedented backlash against American Muslims."

Muslims are fighting back against the stereotype, with social media offering a potential opportunity to change perceptions, said Khurram Dara, author of the books "Contracting Fear" and "The Crescent Directive: An Essay on Improving the Image of Islam in America."

But that's not the role that Hassan envisions for Tutlub.

"Our aim is to help Muslims to be better Muslims, showcase the best examples of Muslims and also help vulnerable Muslims from [being] misled," Hassan said.