Living 'gut-on-a-chip' to help study intestinal disorders

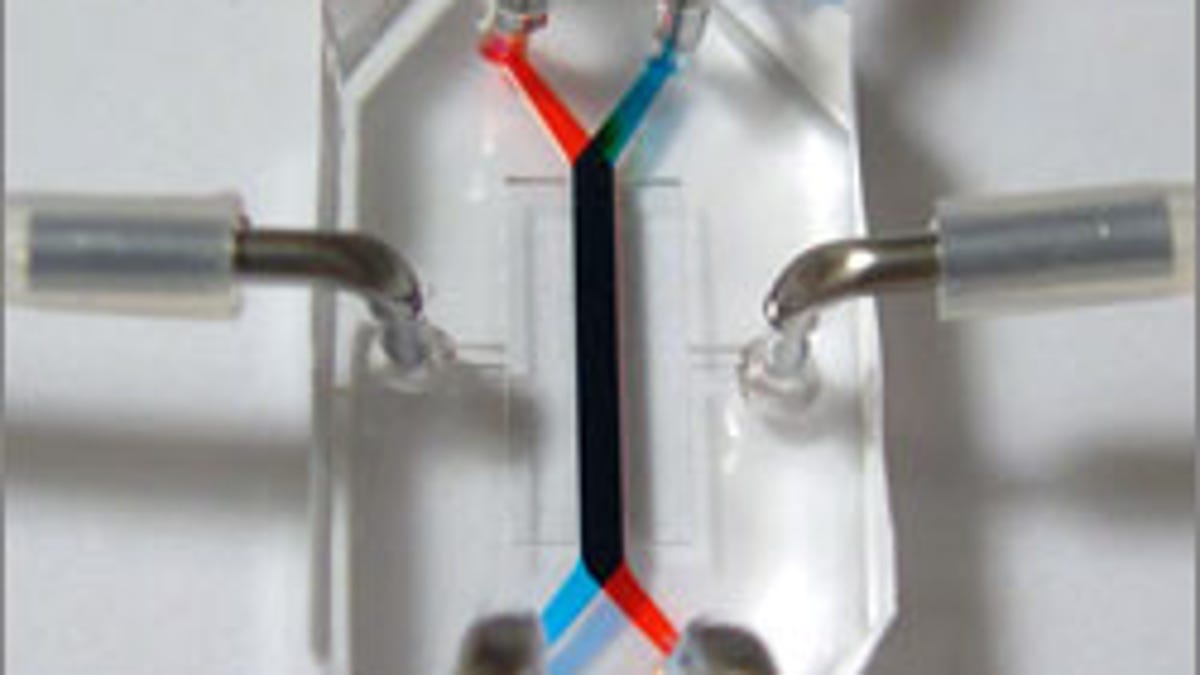

The silicon polymer device, lined by living, human cells, mimics the 3D structures, behaviors, and environment of the human intestine.

After describing a living, breathing "lung-on-a-chip" in Science back in the summer of 2010, Harvard researchers are now reporting in the journal Lab on a Chip on their latest endeavor: a human gut-on-a-chip.

These bio-inspired micro devices that mimic the structures, behaviors, and environments of human organs could help scientists better understand the inner workings of a variety of diseases and disorders -- in this case intestinal ones such as Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis -- without resorting to often less reliable animal testing.

The latest so-called "gut-on-a-chip" is a silicon polymer device whose central chamber is lined by a single layer of human intestinal epithelial cells that recreate the intestinal barrier by growing on a flexible and porous membrane. The device mimics the movement of food along the digestive tract as well as the flow of blood through capillaries.

The researchers report that they were even able to grow (and support) common intestinal microbes on the surfaces of the intestinal cells, mimicking various physiological features that could help understand diseases.

"Because the models most often available to us today do not recapitulate human disease, we can't fully understand the mechanisms behind many intestinal disorders," lead researcher Donald Ingber, a founding director of Harvard's Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering, said in a news release. This means, he adds, "that the drugs and therapies we validate in animal models often fail to be effective when tested in humans."

In addition to being an in vitro diagnostic tool to help develop new therapeutics, Ingber's gut-on-a-chip might even be able to test the metabolism and oral absorption of drugs and nutrients.

The institute is also using DARPA funding awarded in 2011 to develop a spleen-on-a-chip to treat sepsis, a bloodstream infection that can be fatal.

See the team's video on their original lung-on-a-chip below: