Litmus-like sensor could detect chemical weapons

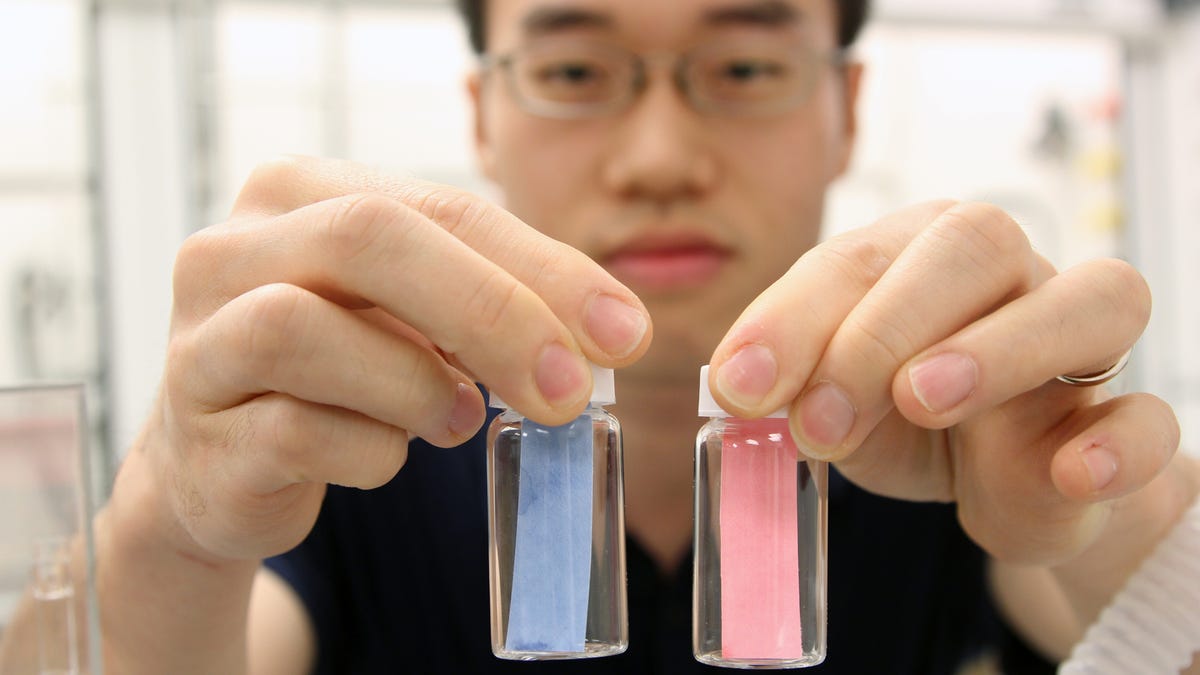

The paper strips are designed to change from blue to pink within 30 seconds of exposure to even trace amounts of nerve gas.

Researchers at the University of Michigan say they have developed a simple litmus-like test for nerve gas that could clue military personnel into when they might actually need to use those heavy masks and protective gear. (Nerve gases, the most toxic of chemical warfare agents, and are colorless, odorless, and tasteless.)

"To detect these agents now, we rely on huge, expensive machines that are hard to carry and hard to operate," Jinsang Kim, an associate professor of materials science and engineering at the University of Michigan, said in a statement. "We wanted to develop an equipment-free, motion-free, highly sensitive technology that uses just our bare eyes."

The paper-based sensors are designed to change from blue to pink in less than 30 seconds when under mechanical stress; the researchers added a group of atoms from a nerve gas antidote that binds to the nerve gas, and the resulting stress triggers the color shift.

To test the sensors (results of which appear in the journal Advanced Functional Materials), the team used a nerve agent simulant that is related to but less toxic than Sarin gas. The sensors detected the simulant at a trace concentration, which the researchers describe as being five times less than the amount required to kill a monkey.

Researchers say the university is now pursuing patent protection for the sensor and seeking partners to help bring it to market.