Lab on a chip puts the pressure on a parasite

A simple device could help researchers better observe how well different compounds fight the increasingly drug-resistant malaria parasite.

Researchers in Canada say they've built a device that will help them study changes in red blood cells caused by the most common species of malaria parasites, plasmodium falciparum, which causes the most lethal form of a disease that claims almost a million lives every year.

The microfluidic device, which is just 1 x 2 inches, is not a diagnostic tool but rather a way to test potential treatments--a crucial step in the fight against malaria, which is constantly evolving to develop resistance to drugs.

Typically, human red blood cells squeeze through capillaries that are narrower than the cells are wide in order to deliver oxygen throughout the body. Malaria, however, deforms and stiffens these red blood cells, which results in jamming and eventually, due to restricted circulation, the death of oxygen-starved tissue and organs.

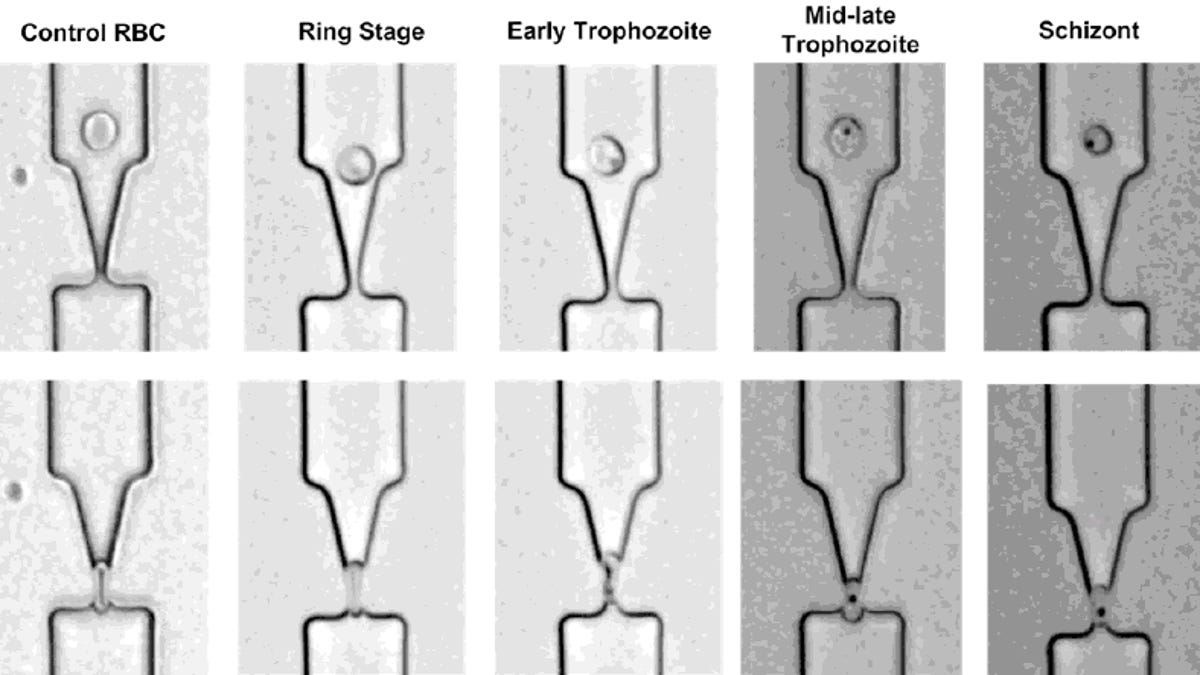

The lab device deforms single infected red blood cells through various funnel-shaped constrictions and measures the pressure required to push the cell through each. (Malaria-infected cells can be anywhere from 1.5 to 200 times stiffer than uninfected cells, making it possible to distinguish between uninfected cells and cells in various stages of infection.) Those metrics can in turn help researchers design new treatments.

"This is an ongoing battle," says Hongshen Ma, the mechanical engineer at the University of British Columbia who designed the device and reports on it this month in the journal Lab on a Chip. "We're running out of malaria drugs because the parasite is becoming resistant to them, so this is a way you can test for chemical compounds to see if you can reserve some of the effects of malaria."

Ma says his team of engineers is now working to automate the device for lab technicians, because they currently operate it manually.