Keeping up with Moore's Law proves difficult for Intel

For the last 40 years, Moore's Law predicted that processors could double in power every two years. Intel acknowledges that it's on more of a two-and-a-half-year cycle.

It may be time for another revision to Moore's Law, if Intel's recent troubles keeping pace are any indication.

In a conference call on Wednesday, Intel confirmed that its upcoming generation of processors, codenamed Cannonlake, will not launch until the second half of 2017 -- nearly three years after the previous generation was made available. To bridge the gap, Intel plans to launch the third iteration of its current-generation processors, codenamed Kaby Lake, in the second half of 2016.

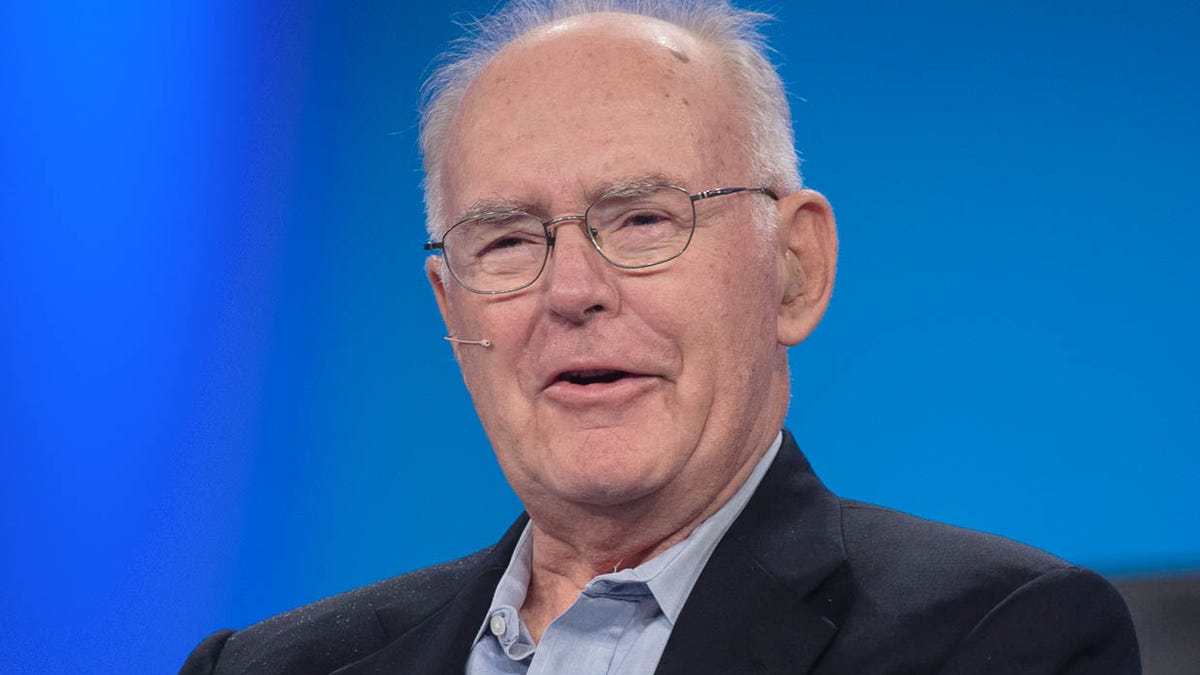

Moore's Law, which was named after Intel co-founder Gordon Moore, is one of the most celebrated ideas in the technology industry. While not a "law," but rather more of a prediction, Moore's Law was posited in a paper Moore published in 1965, predicting that every year for at least the next decade, processors would shrink in size and the components within them would double. In 1975, after his prediction held up, Moore revised his 50-year-old estimate, saying that the doubling effect would occur every two years as manufacturing issues and costs started to rise. Since then, his prediction has held true...until recently.

Intel, whose processors power most of the world's desktops and laptops, struggled to deliver its Broadwell chip -- the first to use a 14-nanometer architecture -- to market due to problems manufacturing the advanced technology. Intel finally began production of the chip in 2014, about two-and-a half years after its previous generation of chip, which was based on a 22-nanometer architecture. The company predicts the same timetable with Cannonlake.

"The last two technology transitions have signaled that our cadence today is closer to 2.5 years than 2," Intel CEO Brian Krzanich said in an earnings call with investors on Wednesday.

What ultimately guides Moore's Law is the idea that the number of components in an integrated circuit, the brains of a computer, would double every two years, thereby boosting performance. In order for that to occur, however, transistors, which switch electrical signals on and off so devices can process information and perform tasks, need to increasingly be added to chips. The more transistors on a chip, the faster that chip can process information.

In order to keep Moore's Law going, processor manufacturers, like Intel, need to make transistors smaller. The original size of a transistor was half an inch long. The next generation of Intel's processors aims at getting transistors down to 10 nanometers, which is smaller than the vast majority of viruses affecting human health. In other words, a 10-nanometer transistor is very, very small.

While Moore's Law is about devices becoming smarter and more powerful over time, the race to make smaller transistors has allowed for "smart" devices to get smaller. Apple's iPhone 6, for instance, is approximately 1 million times more powerful than an IBM computer produced in 1975. The iPhone 6 can fit into a pocket; the IBM computer took up an entire room.

One other contribution Moore's Law has made to the chip industry? It's kept companies on track.

"Rather than become something that chronicled the progress of the industry, Moore's Law became something that drove it," Moore said in an online interview with semiconductor industry supplier ASML in December.

Still, as Intel's acknowledgement of a new lifecycle shows, Moore's Law is becoming harder and harder to stick to. Costs to develop processors are constantly on the rise and with demand for PCs -- long a driver of advanced chip technology -- slower than Intel and others would like, companies are looking at ways to maximize revenue on the products they already have.

Despite the slowdown, Krzanich isn't ready to give up on Moore's Law just yet. He told investors that predictions of the death of Moore's Law have been "disproved...many times over" in the past. He also signaled hope that Intel could get back to a two-year update cycle in the future.

Intel's talk of Moore's Law followed the announcement of better-than-expected earnings for the second quarter. The company posted a profit of $2.7 billion on $13.2 billion in revenue.