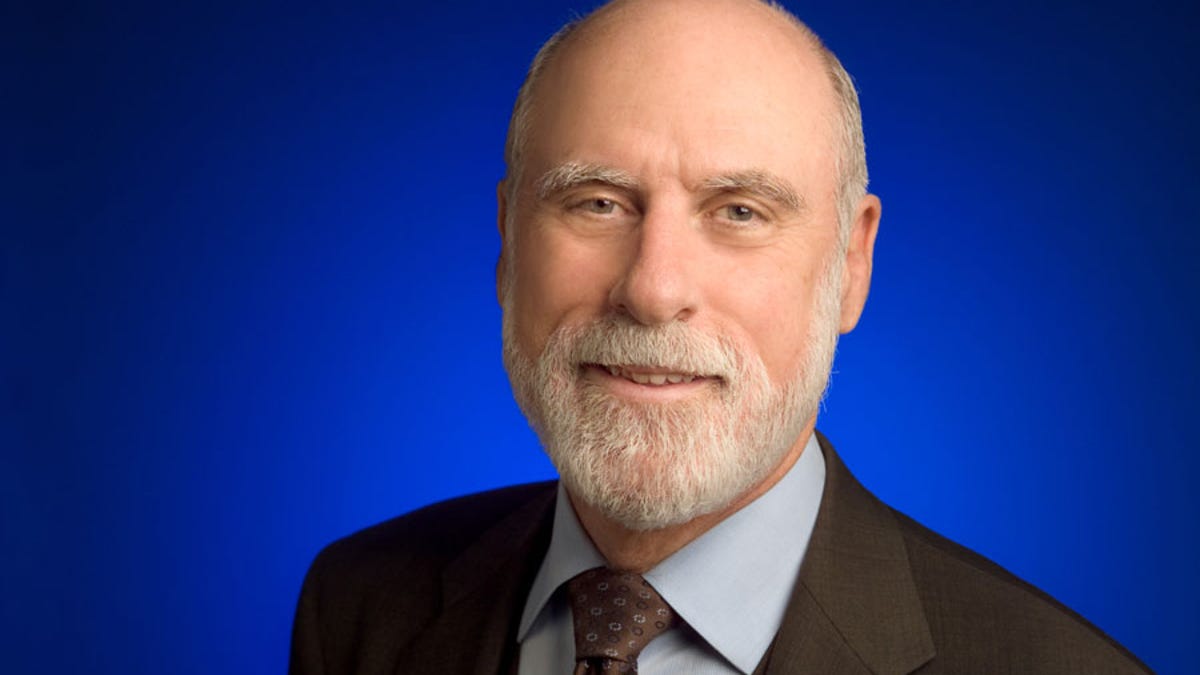

Internet co-creator Vint Cerf welcomes IPv6 elbow room (Q&A)

Google's Internet evangelist, responsible for the address shortage on today's Internet, is anxious for IPv6 improvements. Also: his views on U.N. regulation, censorship, bandwidth caps, and .google.

"Predicting is hard, especially about the future," quips Vint Cerf -- and he should know.

That's because about 30 years ago, when the now-famous engineer was helping to design the technology that powers the Internet, Cerf decided just how many devices could connect to the network. His answer -- 2 to the 32nd power, or 4.3 billion -- looked awfully big at the time. A few decades later, we now know it's far short.

Accordingly, Google's chief Internet evangelist and one of the few people at the company who looks natural in a suit and tie, is eager for tomorrow's high-profile World IPv6 Launch. The event will usher in a vastly larger Internet as many major powers move permanently to the next-generation Internet Protocol version 6 technology. IPv6 is big enough to give a network address to 340 undecillion devices -- that's 2 to the 128th power, or 340,282,366,920,938,463,463,374,607,431,768,211,456 if you're keeping score.

The change actually began years ago: IPv6 was finished in 1996, IPv6 networks could be constructed since 1999, and any personal computer bought in the last few years can handle IPv6 if configured properly. But because IPv4 was spacious enough for a long time, moving to IPv6 was a potentially expensive hassle that didn't have much immediate payoff. It was only last year, when the pipeline of unused IPv4 addresses started emptying out, that a sense of real urgency gripped the computing industry.

The IPv6 transition will take years as Internet plumbing gradually is updated with the ability transfer packets of IPv6 data from point A to point B. That transfer uses technology that Cerf and colleague Bob Kahn invented in the 1970s. It's called TCP/IP, and it's what wires together the Net's nervous system.

When you download that cat photo from a server, it's the job of the Internet Protocol (IP) to deliver it, broken down into a collection of individual data packets, to your computer. Countless network devices in between examine the IP address of each packet to send them hop by hop toward to your machine so IP can reassembles them into the photo.

Closely paired is Transmission Control Protocol, which takes care of ensuring the packets are successfully delivered over this packet-switching network, requesting missing packets be retransmitted if necessary, and reassembling them into the proper order to reconstitute the original photo. Curious people can read the original paper, A Protocol for Packet Network Intercommunication (PDF), written before TCP and IP were split into separate technology layers.

Cerf is a somewhat unusual figure in today's Internet development realm. Hotshot young programmers are pushing the limits of Web programming and other novelties, but Cerf, born in 1943, has a much longer history watching the cutting edge advance. He witnessed the arrival of e-mail, e-commerce, and emoticons.

He even looks the part of a father of the Internet, balding but with a neatly trimmed white beard. And he remains an active parent: in the last two weeks, he warned the U.S. House of Representatives about the perils of U.N. regulation of the Internet, revealed Google's plans for new Internet domain names such as .google, was named president of the prestigious Association for Computing Machinery, and in a speech at the Freedom to Connect conference warned that blocking legislative successors to SOPA and PIPA might not be so easy.

Cerf spoke to CNET's Stephen Shankland in recent days in an e-mail conversation -- though for those who appreciate the Internet's newer communication mechanisms, Cerf will hold a Google+ hangout about IPv6 at noon PT today.

What do you think of the World IPv6 Launch event? Where on the spectrum of PR puffery and real engineering work does it lie?

This is not puffery. It is incredibly hard, painstaking work by engineers looking to make sure that every line of code that "knows" an IP address is 32 bits long in a certain format also "knows" that it could also be in IPv6 format, 128 bits long. This is a major accomplishment for ISPs and application providers around the world. The router and edge device providers have mostly done their homework years ago, but the ISPs and app providers are largely just getting there.

Are you surprised that it took as long as it did for people to start moving to IPv6?

Yes. We hoped for much earlier implementation. It would have been so much easier. But people had not run out of IPv4 and NAT boxes [network address translation lets multiple devices share a single IP address] were around (ugh), so the delay is understandable but inexcusable. It is still going to take time to get everyone on board.

Why did you settle on 2^32 for the IPv4 address space? And when exactly did that happen?

Bob Kahn and I estimated that there might be two national-scale packet networks per country and perhaps 128 countries able to build them, so 8 bits sufficed for 256 network identifiers. Twenty-four bits allowed for up to 16 million hosts. At that time, hosts were big, expensive time-sharing systems, so 16 million seemed like a lot. We did consider variable length and 128-bit addressing in 1977 but decided that this would be too much overhead for the relatively low-speed lines (50 kilobits per second). I thought this was still an experiment and that if it worked we would then design a production version. The experiment lasted until 2011, and now we are launching the production IPv6 on June 6.

Ha! So if this is Internet 1.0, when will we have to move to version 2.0? Is there anything else disruptive at the level of IPv6 we'll have to endure, or have we laid a foundation for incremental improvements now?

New GTLDs [generic top-level domains such as .hotel], internationalized domain names, new mobile applications, delay- and disruption-tolerant networking, the interplanetary Internet, the Interstellar mission -- there is still a lot that can happen.

We're outgrowing its limits today, but what would the consequences have been if you'd picked a bigger than 2^32 back in the 1970s?

I think this would not have passed the "red face" test -- too much overhead, and what argument in 1973 or 1977 would have led to agreement that we needed 340 trillion trillion trillion addresses?