Inside NASA's attempt to take humanity back to the moon

When you're standing a few miles from a rocket launch, it's hard not to feel like a part of history.

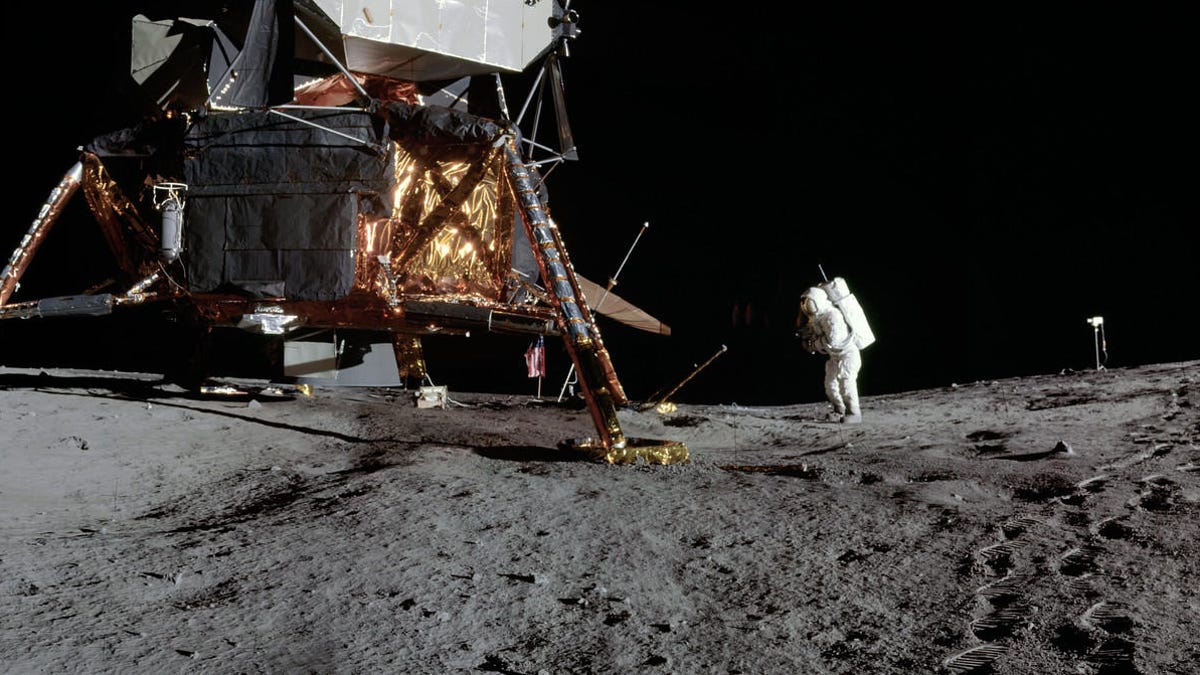

Click here for To the Moon, a CNET series examining our relationship with the moon from the first landing of Apollo 11 to future human settlement on its surface.

On July 16, 1969, the Apollo 11 mission to the moon launched atop a Saturn V rocket from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station in Florida.

That was 50 years ago.

It was a launch that represented a triumph of human achievement and engineering, a frighteningly dangerous foray into the unknown.

It's a moment that feels otherworldly, an event normally experienced via grainy archival footage and crackly audio recordings, but now, half a century later, NASA is planning to go back to the moon. And at the space agency's latest launch, I got a front row seat to the awesome promise of space travel.

I got to watch a rocket take off live and in person.

Turns out, it doesn't matter whether you're experiencing the very first manned mission to the moon in the 1960s or the next step in space discovery in 2019 -- a sonic boom is still the best sound you'll ever hear.

Launching a rocket off a rocket

Orion's Ascent Abort 2 test rocket, the day before launch, at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station.

In the early hours of July 2, NASA conducted the Ascent Abort 2 (AA-2) test flight at Cape Canaveral. The launch was the final test flight for the Artemis mission, which is set to send the first woman and the next man to the lunar surface aboard the Orion spacecraft in 2024.

The Orion abort test launch lit up the sky.

This was the last stop before the moon, the final chance to test the critical systems that will pull the command module and our astronauts inside to safety if anything goes wrong. From here, the next stop is human beings landing back on the moon (and, eventually, missions on to Mars).

After the rocket climbed to roughly 44,000 feet and reached speeds around Mach 1.08 (almost 830 miles per hour), the team fired the abort motor on the Orion test vehicle, separating the command module from the launch vehicle. Just 3 minutes and 13 seconds later, the command module splashed down in the ocean.

From where I was standing, on the roof of a building more than three miles away from the launchpad, the sound of the splash came as an almighty roar.

And once the early data had come in, shortly after the launch, the verdict was clear: If the Launch Abort System performed like this during an actual flight, the crew would survive.

It was a short test, but according to Charlie Precourt, a former NASA shuttle astronaut and head of the propulsion division at Northrop Grumman (the company that built the rocket systems for the abort test), it was far from simple.

The trail left by the Orion test rocket.

"I like to describe it as launching a rocket off of a flying rocket," he told me shortly after the launch. "It's tough enough to fly a rocket off a still launch pad -- the launch pad for our launch abort system is actually a moving rocket at very high speeds, so it's a very complicated set of computer algorithms that guide the firing of the motor."

This test flight was a long way from the Apollo launch -- there were no astronauts on board, and the test rocket was significantly smaller than the Saturn V -- but being on the ground at Cape Canaveral was the closest I've ever felt to that historic event.

On the ground

A rocket launch is exhausting, even if you're just watching.

The day before the AA-2 test flight, I woke at 4 a.m. and drove out to the Kennedy Space Center with CNET video producers John Kim and Logan Moy. As the only foreign national in our group, I could only go as far as the badging center on the perimeter: A NASA escort would take me (and two lovely Dutch photographers) beyond the gates and into the Cape Canaveral Air Force Station. Once we were through, the full scale of NASA's operations became clear. Fifty years of history came into full view.

Remote cameras set up to capture the rocket launch, complete with jury-rigged camera housings.

As the sun rose behind us, we bussed out to the launchpad. The test vehicle was in the final preparation stages before launch. The biting insects had formed hunting packs.

We shuffled off the bus and joined the crew of veteran photographers as they began setting up their remote cameras. These cameras -- positioned in an area near the launchpad that would soon be off limits to press -- were all set up to trigger remotely or at the sound of the blast. Each photographer has their own technique for getting a camera to trigger at the right time while staying in focus (and with enough battery) to capture the perfect shot. "Ask each photographer," I was told. "They'll all give you a different method."

While the photographers jury-rigged tin foil and cling film casings around their DSLRs, we trekked down the hill to take photos. I swatted away wasps, sweated in the humidity and almost stepped on an alligator. (Turns out even the tightest levels of NASA security can't stop a six-foot reptile from setting up camp in the grass a few feet away from me.)

I saw an alligator at Cape Canaveral and I'm an American now, AMA... pic.twitter.com/Ez9s3SEVDs

— Claire Reilly (@reillystyley) July 1, 2019

Coming to terms with my own mortality, I was back on the bus driving across to see the mobile launcher that will eventually provide the launch support structure for Orion, as well as the massive crawler transporter that had moved the launcher into place.

In all the busing around, I was hit with the overwhelming feeling that the more things change, the more they stay the same.

Here I was, 50 years after the Apollo 11 launch, doing the same tours reporters and observers would have taken back then. And cursing the July heat and feeling my hand stick to the paper as I took down notes.

We drove past rows of low-roofed industrial buildings, unchanged from NASA's early days, when the space race was at its most intense and Soviet rivalry saw an entire industry spring up on the space coast in a decade. These buildings -- all midcentury modernism and utilitarian white paint -- popped up here and there in the marshy landscape as we drove around the base, looking like they'd appeared overnight. Knowing the rush to get to space in the '60s, they probably did.

In the press building, the names of famous CBS anchor Walter Cronkite and Jack King (NASA's public affairs officer during the Apollo 11 launch and the man who narrated the launch day countdown) were inscribed into plaques on the wall. As I answered emails on my cellphone, I noticed faded stickers glued to the tables: Phone lines must be reserved before use. That felt like the biggest relic I'd seen on this tour.

And then the launch itself, seen from the roof of an old Air Force building. The countdown, the anticipation and then the fierce explosion and brilliant plumes of smoke. And of course, the thunderous roar as the sound hit us seconds later.

Next stop: The moon

Waiting for the Orion test launch at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station

"So! D'ya get anything good?"

Packing up our gear, we were soon comparing shots and talking about which rocket parts were jettisoned where. Some of the photographers here seemed like they could have been around since those early Apollo days. One wore a baseball cap so completely obscured by commemorative mission pins he looked like a decorated soldier.

Sitting back on the bus, it was easy to feel drawn back to the early days at Canaveral. The technology might have changed -- the rockets more advanced, the systems more refined -- but the overarching the goals haven't changed all that much since the '60s.

Just like Apollo 50 years ago, the Artemis mission will reach out to space to extend the human race farther than it's been. While Artemis is treading familiar ground by going back to the moon, NASA is extending its grasp further.

"Our goal now is to go further, for longer durations," Orion Program Manager Mark Karasich told me from the Kennedy Space Center. "And our goal is to go to Mars, initially, and eventually take humanity across the solar system. The moon this time is a place where we're going to develop and practice our techniques for going to these other destinations."

At the press conference after the launch, he was talking about ticking off the next goal on NASA's list.

"The next big check mark is the moon," he said.

But this time, the moon truly will be one small step -- a step in a bigger journey that could see us becoming a multiplanetary species.

Which leads us back to that sonic boom and the Orion test flight at Cape Canaveral. This wasn't the biggest rocket NASA has launched, and it certainly won't be the last. But waking up at the crack of dawn to trek out to the space coast on that Tuesday morning, I realized this is part of a big leap forward. Just as it was for those first people who braved the July heat to watch the Apollo launch 50 years ago, this is part of something bigger.

As Charlie Precourt, the former astronaut, told me shortly after the launch, space launches truly never get old.

"Did you hear the rumble of that thing?" he asked me. "You never get tired of that."

Originally published July 5, 5 a.m. PT