IBM memory advances could speed up your phone

With improvements that lower its cost, phase-change memory stands a better chance of commercial success than ever before.

Ever wanted to pound your PC as it crawls through a restart or fumed that your phone takes much too long to launch an e-book app? IBM has some good news for you.

On Tuesday, Big Blue announced an improvement to a technology called phase-change memory (PCM) that could uncork these bottlenecks. PCM has been in development for years, but IBM believes it will now become affordable enough to end up in your devices.

PCM could improve services at companies like Facebook, too, that need instant access to massive amounts of information.

Haris Pozidis, the IBM researcher who described the improvements at a memory conference here in Paris on Tuesday, believes PCM could become a commercial success in 2017.

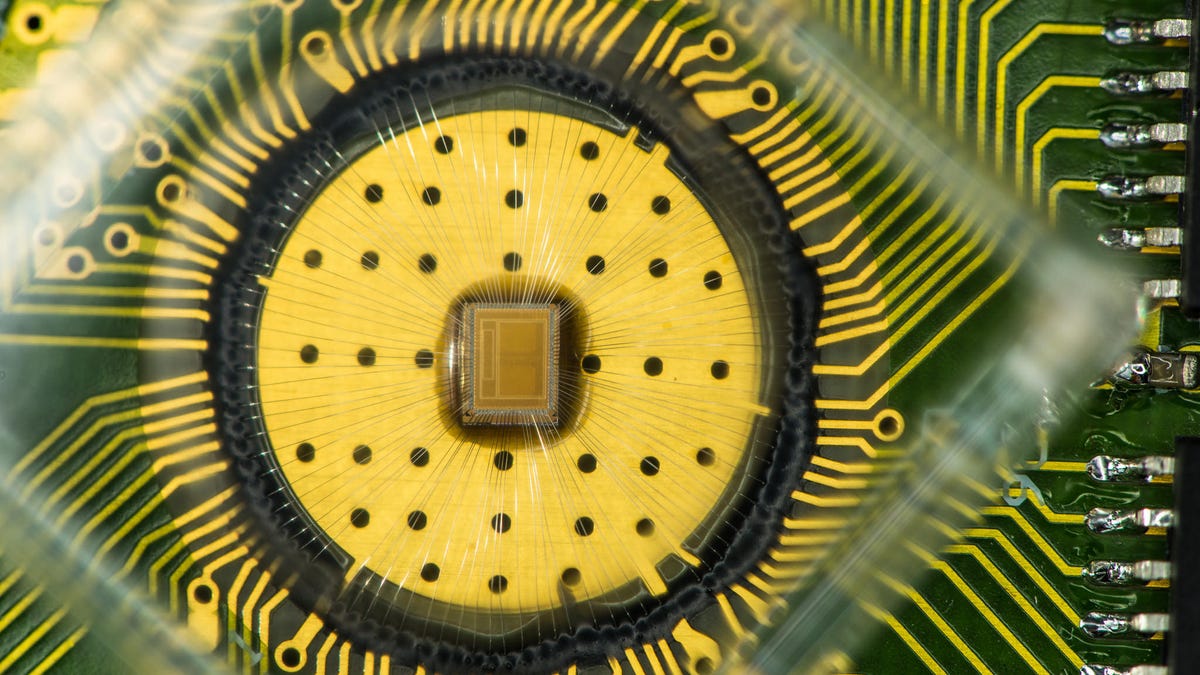

PCM works by electrically heating a tiny amount of a special glassy material built into a chip. How each cell of material cools determines what data it stores. When a cell cools gradually, atoms order themselves into a crystalline pattern. When the cell cools rapidly, atoms form a disorganized hodgepodge instead. The crystalline state transmits electricity well; the jumbled amorphous state doesn't. Detecting that difference lets a computer know whether the cell is storing a one or a zero -- a single bit of information.

IBM has refined the technology to store more bits. In 2011, the company figured out how to store two bits of data in a PCM cell.

And Tuesday, Pozidis announced the ability to hold three bits of data. Cramming more data into a chip means PCM lowers its cost and improves its competitive chances against prevailing memory technologies.

It's easy to take for granted the steady progress in computing technology. But behind every faster network and every thinner laptop are countless researchers laboring for years to wring the most out of physics and chemistry. Commercializing new technology is another hurdle: Just ask Intel, Samsung, SK Hynix and other phase-change fans that have struggled to bring PCM to market.

Today's phones and laptops use two other technologies to store data: fast, expensive and power-hungry DRAM (dynamic random access memory), and slower, cheaper flash memory, which stores data even when the power is switched off. (Hard drives, still common in PCs, serve a role similar to flash but are significantly slower, cheaper and more spacious.)

PCM fits neatly between DRAM and flash. DRAM is five or 10 times faster at retrieving data as PCM, but PCM is about 70 times faster than flash, which is why a PCM-powered phone could load apps fast or a PC could reboot more swiftly than a flash-equipped model. IBM expects PCM to be cheaper than DRAM -- and eventually as cheap as flash.

Matching flash will be tough. Manufacturers continue to improve flash, which is why a first-generation iPad had a maximum of 64GB of flash memory but today's iPad Pro reaches 256GB.