How injectable nanogel could help fight diabetes

Nanotechnology could remove the finger prick from the daily routine of people with diabetes with an injectable gel that monitors blood-sugar levels and automatically secretes insulin.

For diabetics who have to constantly manage their blood-sugar levels, insulin works. The problem is, many people with Type 1 diabetes have to prick their fingers multiple times a day to monitor their levels, and inject themselves with insulin when those levels are too high. And they don't always administer the right amount at the right time.

Researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Boston Children's Hospital hope to automate insulin delivery with a novel nanotech approach that involves injecting a gel that detects blood-sugar levels and secretes insulin when needed -- with a single injection doing do the trick for as many as 10 days.

"With this system of extended release, the amount of drug secreted is proportional to the needs of the body," says Daniel Anderson, an associate professor of chemical engineering, in a school news release. Anderson is the senior author of the paper describing the system in the journal ACS Nano.

Because insulin delivery is so time-consuming and important to get right, researchers have spent years trying to improve the approach, with some developing systems that basically mimic the pancreas to both detect glucose levels and secrete insulin. One approach, for instance, relies on hydrogels, but they have responded too slowly and lacked mechanical strength to the point of letting insulin leak out.

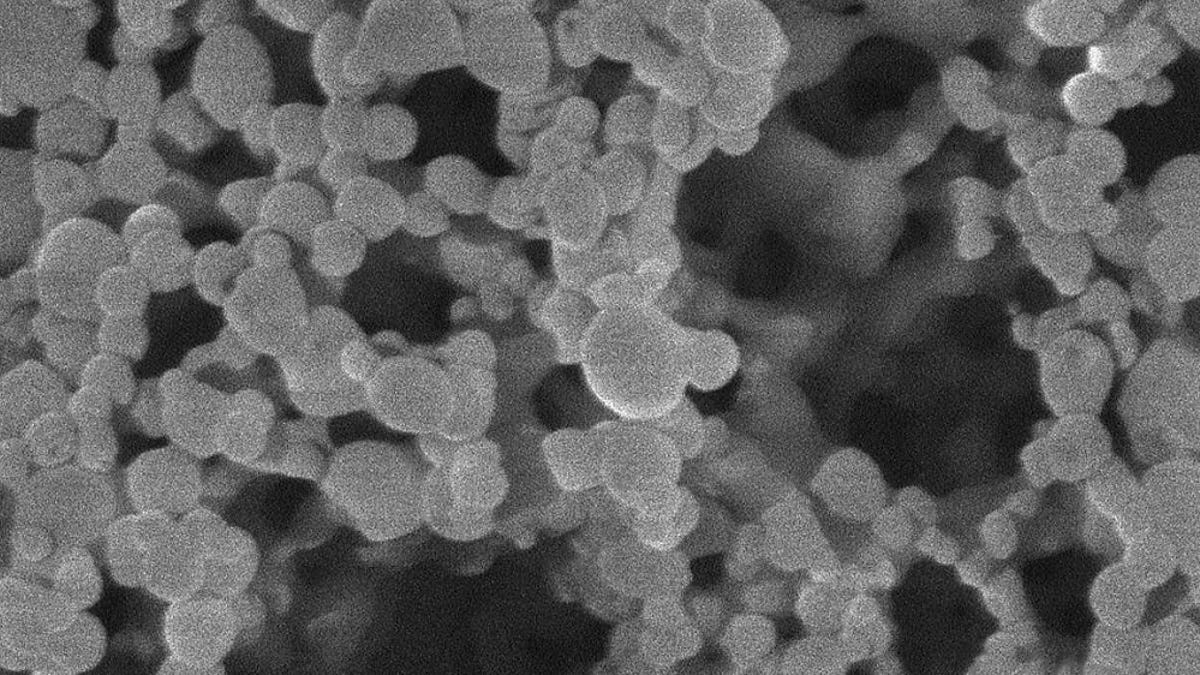

The MIT approach uses a nanogel with a structure similar to toothpaste, containing a mix of oppositely-charged nanoparticles that attract one another and thus keep the gel mechanically strong. With the help of spheres of dextran packed with an enzyme that converts glucose into gluconic acid, glucose can diffuse through the gel, so that when blood-sugar levels are elevated the enzyme produces more gluconic acid to disintegrate the dextran spheres and release the insulin.

Thus far, the team has tested the system on mice with Type 1 diabetes, and in those animals the single gel injection maintained normal blood-sugar levels for an average of 10 days. Eventually, the particles -- which are biocompatible -- simply degrade into the body.

The next step is to get the particles to respond to changes in glucose fast enough to fully mimic the performance of pancreas islet cells in healthy animals without diabetes. In order to test this system in humans, the researchers are tweaking its delivery properties and optimizing the dosage required for humans as opposed to mice.