How do we reemerge after a year of isolation and anxiety? MIT's Sherry Turkle has advice

The MIT professor sees the beginning of a rebirth and an acute need for greater empathy.

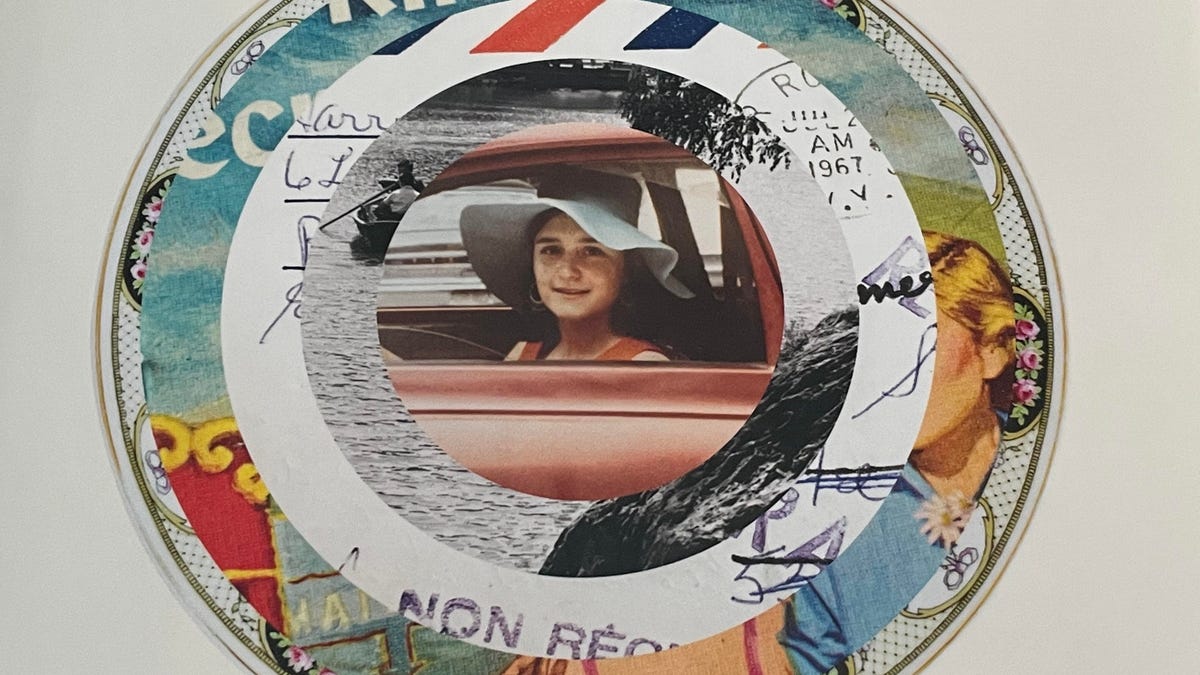

The cover art of Sherry Turkle's book, The Empathy Diaries: A Memoir.

The world's slowly opening up again, and a year-plus of the pandemic now feels like it's starting to fade away. But not entirely. Not yet. Not for many people. And in the meantime, my anxieties about reentering the world are very real and very powerful. I've also developed a deeper co-dependence on screens and tech than I've ever had before. A conversation with Sherry Turkle helped me realize I'm not alone, and that my sense of removal from the world could also be a strength.

Sherry Turkle is an MIT professor whose has worked on social science, psychology and our relationships to technology for decades. Her work has followed me everywhere. Twenty-five years ago I wrote and directed a play about chat rooms that was inspired, in part, by Turkle's 1995 book Life on the Screen. Her 2011 book Alone Together, about the ways screens can distance us from intimacy, helped me when my dad passed away. 2015's Reclaiming Conversation made me think about the rise of immersive theater and real-world experiences. I read Turkle's latest, The Empathy Diaries: A Memoir, this March. As vaccinations promise a new post-pandemic world after a year of distance and isolation, the book's been on my mind as I think about reconnecting with the real world more. After a year of living virtually, it's hard to imagine how to merge that life with the one that's half-emerging.

The Empathy Diaries isn't so much about new technology. It's a journey to the past: Turkle's early life, how she started her research focus. A lot takes place in the 1950s through the 1980s. It's a beautiful chronicle of how Turkle came to study the psychology of how people engage with technology. It also made me reconsider the definition of empathy, and rethink what our relationship with devices really represents.

Much like other works from authors like Jaron Lanier, who questions our relationship with technology in You Are Not A Gadget and Dawn of the New Everything, Turkle's work has helped ground me and comfort me. I found her latest perspective a helpful lens to apply to a suddenly changing world.

I had a conversation with Turkle over the phone (not Zoom, for reasons you'll learn below) about the past year, our lives in the pandemic and what comes next.

Sherry Turkle

Where Zoom, and tech, fail us

"I'm delighted that we have a call, rather than a Zoom," Turkle told me as we started our conversation. After a year of teaching students over Zoom, which Turkle says has been nevertheless successful, she sees a loss of intimacy and attention.

"The reason I'm glad we're not Zooming is that in Zooming, in order to make eye contact with you, I'm looking at that little green light, so you will have the feeling of my attention. That can only happen if I'm making eye contact with you, which can only happen if I'm looking at the little green light, which means that I see nothing … I'll see no turn of your head or when your body tenses, or what your facial expression is. Every once in a while I might dart my eyes away to kind of get a little glimmer of it, but basically, I leave myself completely like an avatar performing into the void."

Turkle remains skeptical, despite tech's assistance during a year of being remote, of how much more technology can meaningfully help us post-pandemic. "My research is showing that people keep saying we can't wait for the pandemic to be over. But a lot of people are saying 'I'm very vulnerable, I'm not sure I even want to step out.' There's so much to take into consideration. Is now the time to suit up and pretend to be somebody else?" Turkle says of technologies like VR, or AI-based companion devices. "And yet, more and more people are calling me about this, and I have this kind of avatar, that kind of avatar, this kind of new product or people can talk pretending to be somebody else, it will be so much easier... Of course it'll be easier, because they're not being encouraged to be themselves. If these gadgets aren't helping me be truly empathic and helping others be truly empathetic so that we can nurture each other and find ourselves and help each other, it's not that I'm not interested, it's not what I think technology is helping most now."

I mention to Turkle that I've seen an explosion of apps that explore the nature of communication -- Clubhouse, or VR office and chat apps, or AI companionship. "In service of what?" Turkle asks, always skeptical. "What's the deep human need? It seems like so many of these apps are pitching either action at a distance or, essentially, a deeper sense of presence at a distance, or on the flip side, the AR trope of superpowers, enhancing your memory, your sense of awareness or something along those lines." Turkle sees a great need for empathy right now over anything else. "Is what we need now a sense of our superpowers, or a sense of our humility? My definition of empathy is, you come from a place of deep humility. And you say, 'I don't know what you feel. Tell me how you feel. And then I'll be in it with you for the duration.' That's not superpowers. That's the opposite of superpowers. That's what we need."

The danger of virtual being a fixture

Turkle is more concerned that this use of screens will continue after everything finally opens back up again. "In a way, we know that we're just on the cusp of giving up some of our screen time, and we're a little afraid, because I think we have missed each other. And we have realized that our former lives took us too much to our screens," Turkle says.

But she's also very concerned that this pandemic era might be the start of a New Normal. "There are so many institutions, and so much power, that is going to try to push us back to our screens after the pandemic is over. Your company is going to try to keep you on your screen because they save money with remote, your educational institution, I mean, a lot is going to try to push us back to our screens. And I think it's going to take a lot of people saying 'No, I really want to get out there and be with people again.'"

Turkle sees pushback from big companies that may continue to see real value in remote work. "I've turned myself now into a fantastic Zoom teacher," she says. But her opinions on how to open up again, and not rely on those tech tools, was inspiring to me as I consider the same.

Turkle also sees it as critical that people speak up now about what hasn't worked. "I think that the companies that are going to win are those who know how to balance people's needs to be with each other, with this desire to save some quick money. As workers, we have to be quite vocal in what our pandemic experience really was. Which was: we were able to do a lot. But there were also things we could not do. And experiences and mentoring that we could not accomplish. And just because this was better than nothing, didn't mean it was better than anything."

When you're with other people, there's no such thing as a screen time limit

I asked Turkle what her advice was for making our way through a time as psychologically challenging as this, where at home I'm still living with kids who have remote school, and where screen times have reached absurd levels. Surprisingly, I got comforting advice.

Turkle has a simple formula for figuring out tech use. "I think if you use the metric, 'Is what I'm doing enhancing my inner life?' I think that as we become more mature, about the internet, about online life, we will become better at answering these questions for ourselves, and less looking to, 'Oh, my god, did I spend too much time online today?'"

"I have a kind of sense that technology, when you enliven it with people, that there's nothing wrong with it. So for example, in raising my daughter, I never had a sort of screen time rule," Turkle says. "I grew up in a house where we watched a lot of television. But we talked to the television and at the television and into the television, about the television. So we would all sit around the television, arguing at the television."

Turkle sees the same rules applying to tools like Zoom. "My daughter and I have a book club. We read books. And then we get on Zoom. I don't for a second worry how much time I'm on Zoom with my daughter. The more I'm on Zoom with my daughter talking about these books, the happier I am. Do I sit around saying 'Oh, too much Zoom time?' No."

Tech like VR and Zoom have birthed a whole universe of immersive performance experiments, and Turkle sees a lot of value in these. "I watch Yo-Yo Ma, doing his Songs of Solace cello performance on Zoom, and I'm so comforted. I love these things that are sort of new forms of art that have appeared on the internet, that show such creativity and ... really what happens when great creative minds are put in a very new situation. It's sort of midway between performance and practice. And it's also things that he wants to play for himself to give him practice, to give him solace. He's not practicing. He's not sharing his practice sessions. He's sharing songs that he would play anyway, to calm him down during these moments. So it was a kind of window into a very intimate time."

What do we do next? (Be easy with each other)

I mention to Turkle that the idea of self-management in a world where many forms of social media and tech are designed to be addictive and often create deceptive bubbles that can feel like a slippery slope. But Turkle also sees a change where people may finally be more aware of the dangers. And, through distance from old habits, be reborn.

"I think there's a Bermuda Triangle of doom between privacy, intimacy and democracy. You can't have intimacy without privacy, you can't have democracy without privacy. Facebook has eroded privacy, intimacy and democracy. Or let's say the Facebook model of scraping your data, selling it, using it. Privacy, intimacy and democracy go together. And I've been trying to make that argument for a very long time," Turkle says. "I think that after 2016, after 2020, after COVID disinformation, after the 2016 election, the 2020 election. I think, finally, people kind of get it. That, you know, something is going on. And it's not clear exactly what to do."

"It's a question really of, what kind of citizens can we be?" Turkle says, adding, "I think we're ready now. As I talk to people and begin to think about how we're coming out of this pandemic, I think people are less naive. I don't want to be Pollyanna about where we are, but I think we're also less naive about where screens can take us educationally."

Turkle also sees a lot of vulnerability that needs to be attended to, as we attempt to return to older familiar habits that now may seem alien.

"I think that there are two stories. I think, first ... everybody is saying, I'm so lonely, and I can't wait to be together. But I think we have to be very gentle with each other, because I'm picking up a second story, which is that being in this contained environment, for a lot of people, has assuaged certain anxieties and vulnerabilities they have. This is not to say that they haven't been lonely, this is not to say they haven't suffered -- but there actually has been an upside to the downside," she says.

"Reemergence is going to have its own challenges. And we have to be very gentle with each other and compassionate with each other. And empathy really is going to be the touchstone as we reemerge. I think for many people, maybe everyone ... there has been something comforting about being able to let go of some of the demands of what our lives are actually like in the world we had created for ourselves."

Visiting old places again with new eyes

Turkle refers to "dépaysement" in her memoir, an anthropological term referring to seeing the world at a distance in order to understand it more clearly. In her book, she uses the tool as a way to relate to living in new places in times of change, like Paris, or as a way to analyze the ways new computer technologies in the '70s and '80s, or the internet in the '90s, disrupted society. As I read her memoir, I thought about how it will feel to commute again, connect again. And even, just to go to stores again. Alien, and also new. And what Turkle reminded me was that there's a secret gift to this year of being isolated that we shouldn't waste.

"Where I'm optimistic with this idea about coming back is that this period of being away, and this period of living a completely different life, has given us a sense of time out of time that I call dépaysement. It literally means decountrifying, it means not living in your country, even if you are in your country. But you know, it's as though you live in another country. So that when you step back into your country, as we're about to do, you see your country differently. I think all Americans have had that experience. We have stepped out of our country. And we've seen our country differently. Some things that we knew, but didn't want to know," Turkle says of the unsettling times in America over the last year.

"But there's a reason that we didn't want to face it. And there's a reason, you know, how do they put it, that the quiet part was being said quietly, and now it's being said out loud. By seeing things anew, we have the potential to really rebuild ... you can't begin to rebuild if you don't see the truth. That's what Victor Turner, this great anthropologist I studied with, calls these liminal moments, these moments betwixt and between, when you have a chance to really begin something new, and start something new."

I'm in the middle of starting things anew right now, but with lots of caution and anxiety. I don't travel anywhere yet. Maybe you've already started traveling. Maybe you feel the same way as me. But in these new and changing times, I don't think there's a better book to read right now than Sherry Turkle's memoir -- it's a reminder on how to be patient, be understanding, be open-minded. And it's an excellent reminder on what empathy truly is.

Read more: CNET's conversations with great authors, about great books