Facebook takes on global Internet bottlenecks

With projects called Terragraph and ARIES, the social network giant hopes to speed Internet access in cities and spread it to rural areas, too.

Freaked out by Facebook trying to fill the skies with colossal drones beaming the Internet at you? The social network giant offered two more down-to-earth technologies on Wednesday to dramatically improve network access across the world.

Terragraph uses high-frequency radio waves to speed up networks where populations are dense. And ARIES aims to replace the slow wireless data service that prevails today in poorer and rural areas with faster, longer-range communications that accommodate more people, too.

The company doesn't plan to build the networks itself. Instead, it'll rely on Internet service providers and carriers, the company said.

That's probably good: a huge global industry is already working on many of the same challenges. The mobile networks that replace today's will become a $247 billion business in 2025, ABI Research expects. Facebook didn't say when it thinks the research projects will to mature into real-world services.

"We don't want to make things just a little bit better," said Jay Parikh, vice president of engineering at Facebook. "We're working on things that will make things 10x faster, 10x cheaper, or both."

The projects, unveiled in San Francisco during the second day of Facebook's developer-oriented F8 conference, show just how out of date you are to think Facebook is merely for keeping up with friends and family. It's the home of the Oculus Rift virtual-reality headset, the WhatsApp and Facebook Messenger communication services, the Instagram photo-sharing service, and as of Tuesday, computer-run chatbots to help businesses answer customer questions. Facebook's work on wireless networks is part of Chief Executive Mark Zuckerberg's effort to spread Internet access to everyone on the planet.

Zuckerberg brings a do-gooder vibe to the aspiration, but universal Internet access also makes business sense. The more people are online, the more they can use Facebook apps and see Facebook ads. Facebook drew controversy in February when Indian regulators rejected Free Basics, its program to offer people no-cost access to a limited number of Internet services -- including Facebook of course.

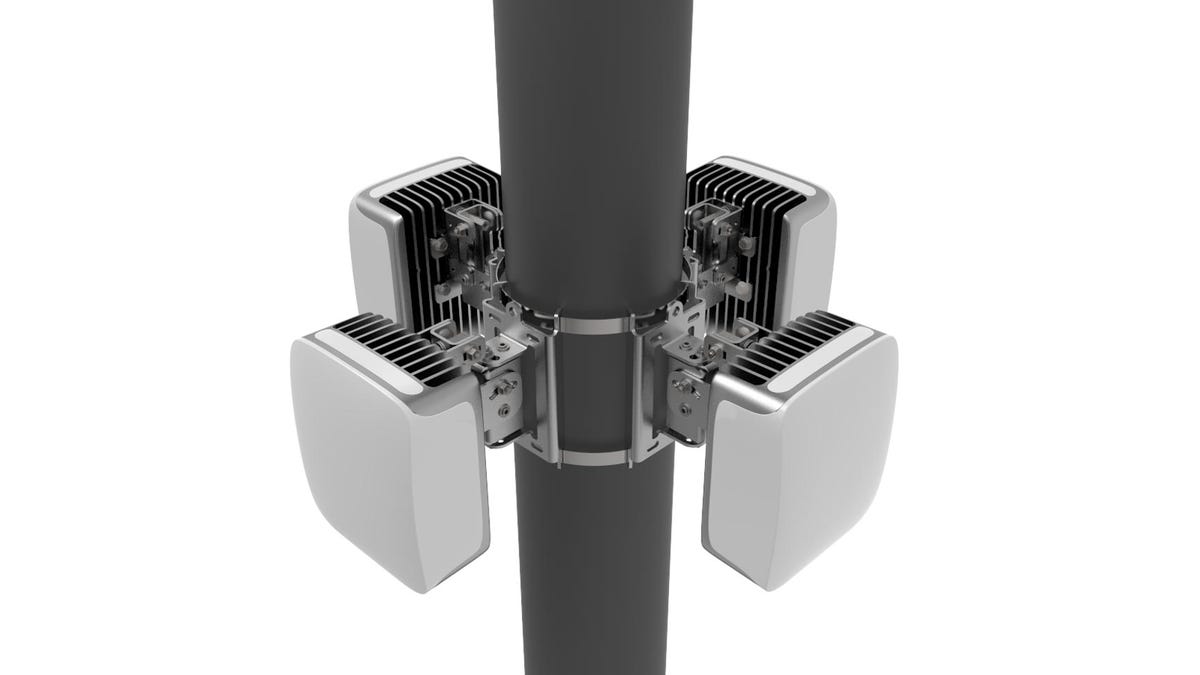

Facebook's ARIES project uses numerous small antennas to beam radio signals in specific directions to extend communication range.

Facebook's highest-elevation ambition has been to connect remote locations to the Net from Aquila, a massive drone the company developed with the wingspan of a Boeing 737. Google and billionaire Elon Musk's rocket company, SpaceX, are also working on beaming Wi-Fi signals from high-altitude balloons and satellites.

Terragraph technology would blanket an area with antennas that could be mounted on streetlights. ARIES would fit onto existing mobile network antennas -- the big towers you'll see by highways and atop buildings.

Terragraph uses a modified version of an existing but uncommon technology called WiGig or 802.11ad. It employs airwaves where radio signals vibrate at 60GHz -- nearly 100 times the frequency used to broadcast TV and connect your phone to the network. These high frequencies are great because they can carry a lot of data and are free for anyone to use without expensive government auctions. But high-frequency radio signals also don't travel as far or penetrate walls as well, so you'll have to be closer to a Terragraph antenna for it to work. Facebook thinks Terragraph base stations will be located every 200 or 250 meters.

Facebook is using the technology on its own campus and plans a trial farther south in Silicon Valley in the city of San Jose, California.

ARIES (Antenna Radio Integration for Efficiency in Spectrum) is at an earlier stage of development. It's goal called spectral efficiency: squeezing as many bits of data as possible over a given region of airwaves. That helps you cram more people onto a network, but ARIES also is designed to improve transmission distances so people in remote areas get access.

In the long run, Facebook hopes, ARIES technology could be incorporated into the fifth-generation "5G" network that is expected to arrive starting in 2020 as a faster, more reliable way to connect our phones, cars and other devices to the network.

CNET staff writer Richard Nieva contributed to this report.