Electroscalpel method identifies cancer in real time

Researchers are pairing the electroscalpel with mass spectrometry to map out with molecular precision--mid-surgery--where and how aggressively cancer is spreading.

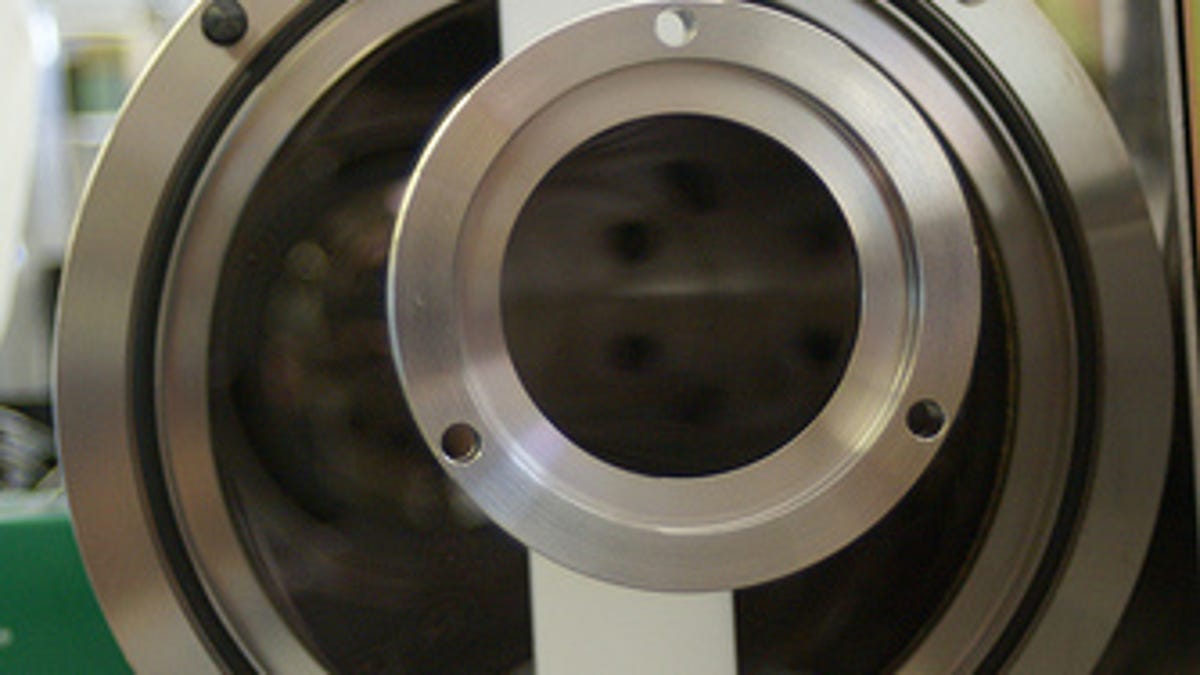

Neither the electroscalpel (a surgical cutting tool) nor mass spectrometry (a technique to identify a molecule's elemental composition by measuring the ratio between its mass and charge) is new. But using the two together may enable surgeons to detect cancerous cells during, instead of before and after, surgery.

"When a surgeon is performing cancer surgery, he doesn't have any direct information on where the tumor is," Zoltán Takáts, a professor at Justus-Liebig University in Giessen, Germany, tells Technology Review. Being able to detect, analyze, and remove cells during surgery might result in fewer surgeries down the road, not to mention a better diagnosis of the type and aggressiveness of a patient's cancer.

Mass spectrometry is already used to detect healthy versus cancerous tissue; unfortunately this analysis requires ionizing the molecules by blasting a stream of charged particles into the sample. A high-voltage nitrogen jet, as Takáts points out, is "not compatible with the human body."

The electroscalpel, meanwhile, emits gaseous ions called surgical smoke, an unhealthy byproduct collected during surgery to protect patients and surgeons alike. Takáts and his collaborators have discovered that the surgical smoke itself is a sufficient sample for mass spectrometry, and that gathering and then analyzing the samples takes a fraction of a second.

"We can draw a map and say this part is healthy liver, that is connective tissue, this is adipose tissue, that is cancer," Takáts says. In fact, his team already has in animals, including rodents, and is working with veterinarians to remove tumors in dogs using electroscalpels. They're currently developing the machinery with Meyer-Haake, a German electrosurgical device company, and are set to start human clinical trials in a matter of weeks.

The biggest remaining hurdle is probably cost, since a commercial mass-spectrometry system tends to start in the six-digit range. But tailoring mass spectrometers to this specific kind of analysis, which doesn't have to be as high-performance as those used in most chemistry labs, could help drive the cost down. Takáts hopes to make one that costs about $20,000.