Dear Apple, what's wrong with shenanigans?

This week, Apple's Phil Schiller took to Twitter to sniff at Samsung's alleged "shenanigans." But, as a CNBC broadcast about JP Morgan underlined, shenaniganing is just part of businessing, isn't it?

Cheaters never prosper.

Except when they do, which seems to be quite often.

So anyone, or indeed, any business that purports to be holier than the one down the road might be reflecting sanctimoniousness rather than fact.

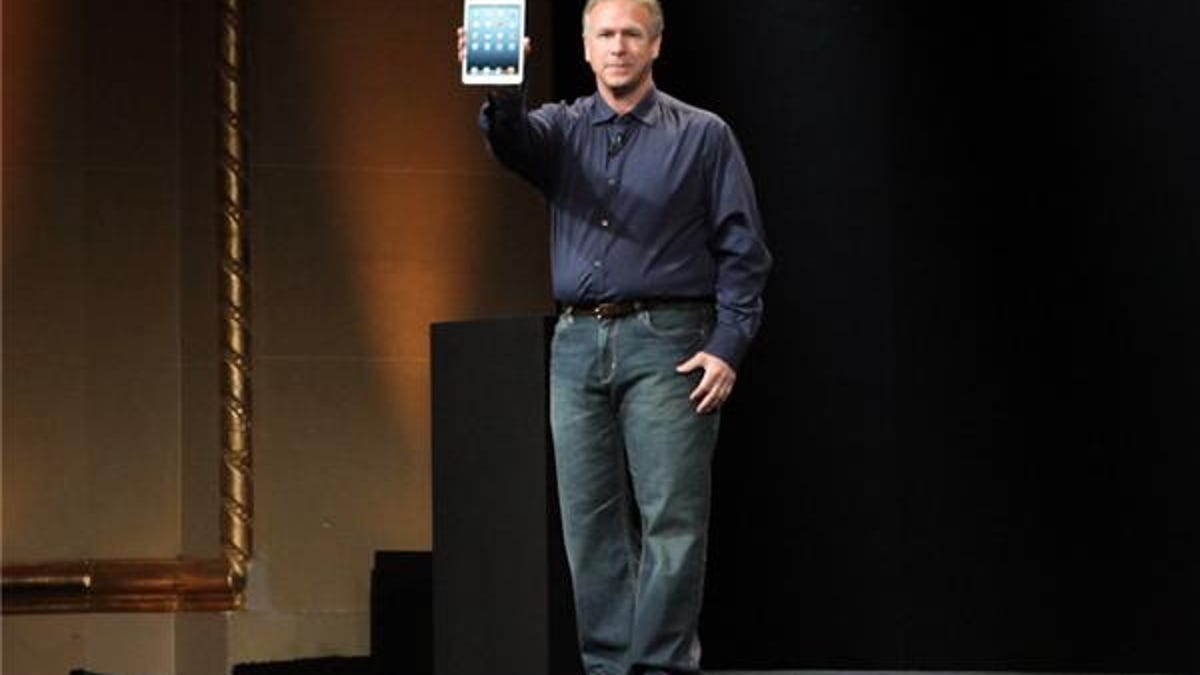

This week, Apple's marketing head, Phil Schiller, breezed onto Twitter to link to a critical report about Samsung's benchmarks on the Galaxy Note 3, which allegedly bloat reality by 20 percent. (Samsung denied it cheated.)

Schiller underlined the word "shenanigans."

Shenanigans are bad things. They are fraudulent, cheating, bending of the rules. Or, as some defendants in court cases and scandals refer to them: "misstatements."

The layperson's eyes and ears seem to be assaulted daily by accusations of shenaniganing. As far back as 2003, a company was accused of, um, misstating benchmarks. That company was Apple.

These days, shenaniganing can take many forms: misstating the power or even dimensions of your product; promising an exaggerated quality of reception, speed, or picture quality on your device; hiring employees from another company, so that they can divulge deep secrets; spying on a company's production line in order to glean what might be coming next; and, the very favorite, stealing a patent owned by another company.

The concept of playing fair in business seems to be about as deep-rooted as the concept of playing fair in the NCAA. Which appears, in itself, to be remarkably like a business.

But I don't take my commercial moral guidance from priests, lawyers, philosophers, journalists, or other peculiar do-gooders. I turn to CNBC.

I keep one eye permanently attached to the swings and ladders of outrageous fortune displayed there. I listen to the state of the world as seen through the State of Money.

This week, the channel seemed to make very clear that a touch of shenaniganing was all in a day's work. In a narrow-ranging discussion about alleged shenaniganing at JP Morgan, the channel's wind-diviners were entirely clear -- at least to my ears -- as to whether it truly matters.

One quite seminal quote from CNBC's Maria Bartiromo summarizes very well. Speaking of JP Morgan and its CEO, Jamie Dimon, she said: "The company continues to churn out tens of billions of dollars in earnings and hundreds of billions of dollars in revenue. How do you criticize that?"

How, indeed.

The attitude toward Alex Pareene of Salon, a critic of corporate shenaniganing seemed to be: "Go over and sit in the corner till we call you to get us some lunch."

The whole segment is truly worth viewing, because it underlines the beauty, purity, and sheer moral joy of making as much money as possible. (I have embedded it for your education.)

I would, quite naturally, hesitate to suggest that all businesses subscribe to the Lombardi principle of winning being the only thing.

But the Lance Armstrongs of the commercial world seem to be relatively rare, when compared with some of the stories that emerge many, many years after the events matter not at all.

You can believe that shenaniganing caused the last, vast recession. But business is a fierce, unending competition. Just like baseball. Sometimes, you have to, you know, scuff the ball, pick at the seam, use a little cream.

I suspect that, these days, allegations of shenaniganing are viewed just as CNBC views them.

"Oh, look. Someone's accusing a corporation of something heinous. Honestly, this is no more than high school, is it?"

Now, what about that share price?