DEA agent caught twisting facts in wiretap request

A federal judge rebukes a Drug Enforcement Administration agent for selective editing in a wiretap request that claimed a conversation about chrome wheels was code for drugs.

When police ask a judge to grant a wiretap order, there's no defense lawyer present to raise objections. The judge has a limited amount of information, all provided by the cops and prosecutors, who in theory will take this solemn responsibility seriously and never lie or twist the facts.

Which brings us to U.S. v. Romero, a relatively routine case in Massachusetts in which Alberto Romero and 17 others were charged with conspiracy to manufacture and distribute crack cocaine.

To get a wiretap against the alleged crack cocaine ring, Drug Enforcement Administration agent Joao Monteiro filed an affidavit on July 8, 2005. The only problem is that Monteiro exaggerated an innocent conversation about automobile wheels--to convince a judge to grant a wiretap.

This, in other words, is where theory meets reality.

Here are excerpts from U.S. District Judge Reginald Lindsay's opinion, dated March 7:

That brings me to the question of the claimed selective editing of the transcript of the May 31, 2005 communications between Romero and Willie. Romero claims that intentional, selective editing, together with Agent Monteiro's interpretation, in light of his "training and experience," made innocent conversations about automobile wheels appear to be conversations about drug trafficking.

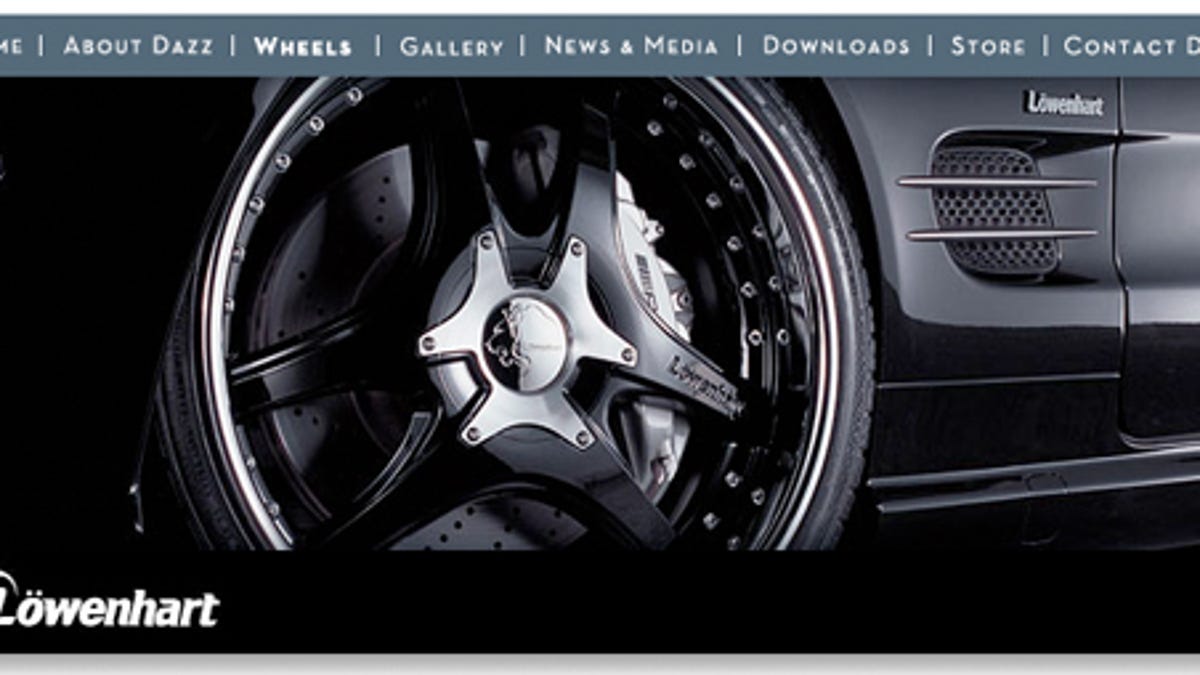

After reviewing both Romero's and the government's translations of the conversation in question, I conclude that the portion of the transcript included in the Supporting Affidavit was, at the least, an overstatement of the degree of certainty with which Agent Monteiro could reasonably have interpreted the conversation to be one concerning drug transactions. The conversations appear to be, in fact, about chrome wheels for an automobile, the wheels being sold under the brand name "Lowenhart."

The government, in its brief in opposition to the present motion, argues that Agent Monteiro, in quoting the conversation, made, at worst, an innocent error. The government explains that Agent Monteiro did not monitor or translate the May 31, 2005 calls from Spanish to English: the monitoring and translation were done by a government contract interpreter. Neither Agent Monteiro nor any of the other officers engaged in the investigation spoke Spanish, the government says.

The problem with the government's explanation is that it is based on information outside the four corners of the Supporting Affidavit. On the other hand, by presenting the full transcript of the conversations in question, Romero has made the showing necessary to justify a Franks hearing, unless the Supporting Affidavit contains other indicia of probable cause justifying the issue of the interception order. I therefore will disregard the May 31, 2005 intercepted conversations. (Note: This is named after Franks v. Delaware, a U.S. Supreme Court case that said when a defendant makes a substantial preliminary showing of false statements by cops, a hearing must be held. --DBM)

I will examine the other information in the Supporting Affidavit to see whether, without the questioned conversations, the Supporting Affidavit fails to provide probable cause for the order authorizing the interception, or whether, at minimum, a Franks hearing is required to determine whether the order is valid without the questioned conversations.

The Supporting Affidavit also was based on information said to have been provided by codefendant Gregory Bing, who, as described in the May 20 Affidavit, and the April 19 Affidavit, had given information to law enforcement officers to the effect that Romero was a large-scale drug dealer...The Supporting Affidavit also points to the following incident as support of the application in question. On May 6, 2005, officers of the Boston Police Department seized $5,000 in alleged drug proceeds from Jose Gonzalez-Padilla (who was linked to Romero)...

I find that the information from the Supporting Affidavit, as described in the preceding several paragraphs, amply provided the issuing judge with a basis on which to find probable cause to authorize the interception of communications on Romero's direct-connect telephone, even in the absence of the questioned, intercepted conversations between Romero and Willie on May 31, 2005.

Kudos to Judge Lindsay for exercising independent judgment and questioning Agent Monteiro's tortured explanation of why he needed to selectively edit a conversation about Lowenhart chrome wheels. Wiretaps are a messy and uniquely invasive investigative tool, and police should be held to exacting standards when swearing out affidavits requesting one. Let's hope Monteiro and his employer, the DEA, will take the judge's rebuke to heart.