CRISPR experts call for moratorium on creating gene-edited babies

Prominent scientists and ethicists believe a temporary pause is necessary.

Eighteen of the world's foremost CRISPR researchers and bioethicists have called for a moratorium on clinical experiments using the revolutionary technology to genetically modify human babies.

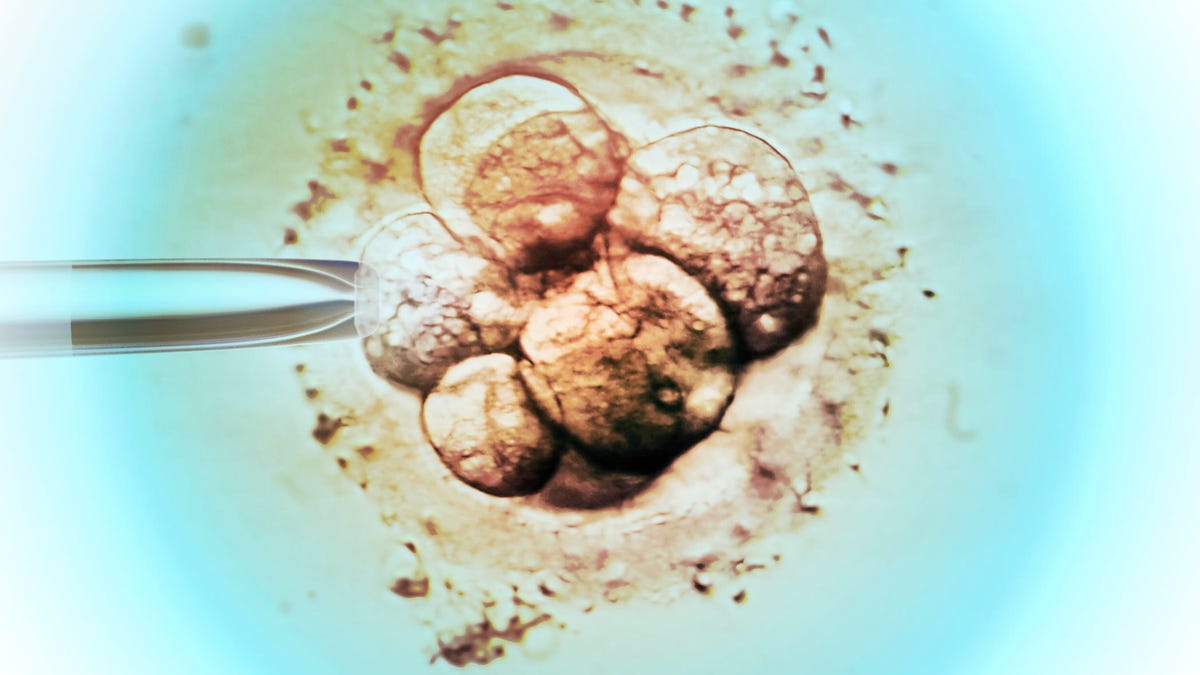

CRISPR, a powerful molecular tool that enables precise and quick genetic edits, was used to create the world's first gene-edited babies, born in a Chinese research program in November 2018. The leader of that program, He Jiankui, flouted international recommendations, using CRISPR to edit the DNA of three embryos that were carried to term.

The revelation that gene-edited babies had been born shocked the scientific community, sparking further debate about regulations pertaining to "germline editing" -- the type which affects affect sperm, eggs and embryos and thus can elicit changes that irrevocably alters the human gene pool.

That has led to the call for a global moratorium, published Wednesday in preeminent science journal Nature, co-signed by CRISPR co-founder Emmanuelle Charpentier, pioneer Feng Zhang and a number of prominent CRISPR scientists from around the globe. The authors are quick to point out a global moratorium would not mean a "permanent ban" but instead a temporary pause in activities, allowing for the establishment of an international framework governing how germline editing proceeds.

This doesn't preclude scientists from using CRISPR for basic research purposes -- scientists would still be able to make edits to sperm, eggs and embryos as long as they were not used to create gene-edited babies. Research on human cells incapable of reproduction ("somatic gene editing") would not be included in the moratorium, nor would CRISPR research tackling non-human problems, such as modifying malaria-carrying mosquitoes or gene-edited chickens.

The moratorium proposed Wednesday would begin with a five-year commitment to not permit any clinical use of germline editing.

The experts write that germline editing is "not yet safe or effective enough to justify any use in the clinic" and the risks are still "unacceptably high". Four years ago, as part of the first International Summit on Human Genome Editing, a similar line of thinking led prominent CRISPR researchers to the same conclusion, though they stopped short of calling for a moratorium.

Gaétan Burgio, geneticist with the Australian National University, says that Wednesday's renewed call for a moratorium "is in line with previous calls".

Adhering to the moratorium would be voluntary for each nation, but for those that choose to permit such experiments, they would need to provide public notice of their intent and justify their activities by evaluating "technical, scientific and medical considerations, and the societal, ethical and moral issues."

Director of the National Institutes of Health, Dr. Francis Collins, released a statement Wednesday addressing the issue.

"Research on the potential to alter the very biological essence of humanity raises profound safety, ethical and philosophical issues," Collins wrote. "Until nations can commit to international guiding principles to help determine whether and under what conditions such research should ever proceed, NIH strongly agrees that an international moratorium should be put into effect immediately."

However, even if the proposed moratorium is agreed to, a number of challenges remain.

Chiefly, Burgio says it will require "broad engagement from the community" and "commitment from various entities and individuals to embrace a moratorium". He believes the moratorium will not prevent "rogue" entities from operating in the space, much like He Jiankui did in creating the first gene-edited babies last year.