Could the sun emit a killer 'superflare'? Maybe -- a big maybe

New research suggests our star might be capable of huge solar flares that could bring modern society to a standstill. The emphasis is on "might."

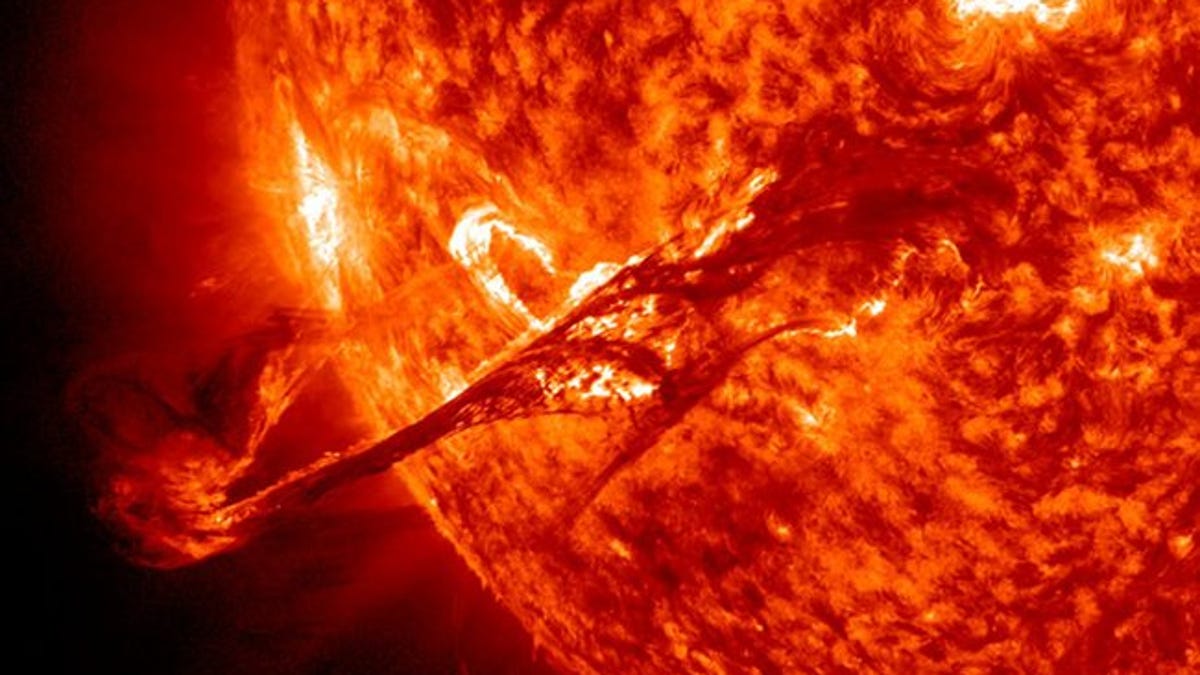

We know eruptions on the sun can hurl energetic particles toward Earth that we see as colorful auroras when they collide with our atmosphere. The most powerful solar flares we've observed can disrupt communications signals and, in rare cases, even affect power supplies on Earth. But could our star hurl a massive "superflare" at us tomorrow?

A few years ago, the Kepler Space Telescope began observing larger numbers of superflares on other distant stars. Superflares can be up to 10,000 times more powerful than the largest documented solar flare. The notion that our sun is capable of such a huge eruption has been dismissed by NASA and others. New research, however, published Thursday in the journal Nature Communications questions the assumption that we shouldn't worry about a gigantic solar hiccup.

"The magnetic fields on the surface of stars with superflares are generally stronger than the magnetic fields on the surface of the sun," explains Christoffer Karoff, of Aarhus University in Denmark, who led the study investigating the question of whether the sun could produce a superflare.

Karoff's team looked at almost 100,000 stars using the new Guo Shou Jing telescope in China. They found that about 1 in 10 of the stars producing superflares had a magnetic field similar to or weaker than the sun's.

"We certainly did not expect to find superflare stars with magnetic fields as weak as the magnetic fields on the sun. This opens the possibility that the sun could generate a superflare -- a very frightening thought," Karoff said in a press release.

Other researchers also see the potential for superflares from our sun, but aren't freaking out just yet.

In December, a team from Warwick University in the UK published research looking at a Milky Way binary star named KIC9655129 that regularly erupts in superflares similar in nature to solar flares. The findings suggest the sun also harbors the same potential for destructive mammoth flares, but stops short of sounding the alarm and recommending that we all stock the fallout shelter with plenty of canned goods.

"If the sun were to produce a superflare it would be disastrous for life on Earth; our GPS and radio communication systems could be severely disrupted and there could be large-scale power blackouts as a result of strong electrical currents being induced in power grids," lead researcher Chloë Pugh said in December. "Fortunately the conditions needed for a superflare are extremely unlikely to occur on the sun, based on previous observations of solar activity."

But Karoff isn't so sure that Earth hasn't already been hit by small superflares between 10 to 100 times bigger than what's been observed in the past century.

"One of the strengths of our study is that we can show how astronomical observations of superflares agree with Earth-based studies of radioactive isotopes in tree rings," he explains.

The Gou Shou Jing telescope is the largest telescope in China. It's also called the Large Sky Area Multi-Object Fibre Spectroscopic Telescope, or LAMOST if you're on a first-name basis.

It's possible to look at tree ring data and see increased amounts of a certain radioactive isotope that is connected with large solar eruptions. Previous research (PDF) has suggested that such small superflares may have collided with the Earth in the years 775 and 993.

Obviously, humanity survived any early solar superflares during the Dark Ages, but what would happen if such a blast were to be shot our way tomorrow?

We've already received small tastes of how a large flare can affect modern society. In 1989, a solar storm caused a power outage in the entire province of Quebec. The largest solar storm documented post-Copernicus was the so-called "Carrington Event" of 1859 that knocked out telegraph systems worldwide and created auroras over tropical latitudes.

Today we rely far more on our electrical and communications infrastructure. And it would be far more vulnerable to massive flares because so much of it consists of satellites in orbit, beyond the full protection of our atmosphere.

If there's any silver lining to our state of cosmic helplessness when it comes to the possibility of massive solar flares, it's that we'd have some warning. Should a destructive solar eruption be shot in our direction, it would likely take anywhere from 18 hours to five days to reach us.

It could be worse though. At least the reality isn't bad as the Hollywood take (click to spoil the end of a really terrible Nicolas Cage movie from 2009) on what a massive superflare might do to us.