Charles Babbage's masterpiece difference engine comes to Silicon Valley

The machine, only the second machine of its kind in existence, is delivered in advance of an exhibition that will open May 10.

Update: This story has been corrected to reflect that the date of the public opening of the exhibit is May 10.

MOUNTAIN VIEW, Calif.--"Excuse me, Richard, we have a very large parcel."

With those words, spoken by John Shulver of London's Science Museum, a day of supreme geekery unfolded at the Computer History Museum here.

To be precise, the package in question was the delivery and installation of a difference engine, a brand new model of a 19th-century-era machine designed--but never actually built--by Charles Babbage. It was designed to be a mechanical calculator which can determine polynomial functions.

However, since Babbage invented the machine and never built it, and the only ones actually constructed were in the 19th century, the first one built in modern times was created in 1991 at London's Science Museum. Much more recently, tech millionaire Nathan Myhrvold visited the London museum and decided he wanted one for himself. So he commissioned the museum to build it for him.

Three and a half years later the machine was finished. But before it goes in Myhrvold's living room, it is going to spend six months on proud display at the Computer History Museum here. And on Wednesday, it was expected to arrive at the Mountain View museum.

However, partly due to the Olympic torch's passage through San Francisco, the grand machine's delivery was delayed for a couple of hours. And so as I--and many others--waited excitedly for its arrival, I was able to have an interesting conversation with Richard Horton, the metals and engineering conservator at the London Science Museum, and the lead engineer on the creation of the brand new difference engine.

Horton was on hand, as was Shulver--who assisted Horton with the last few months of the construction, for the arrival and installation of the machine.

He told me that he had been selected to build the new difference engine because he had been the one to craft a special Babbage-designed printer that was part of the Science Museum's machine. This, of course, after Myhrvold ponied up the million dollars needed to make another one.

Horton said that Myhrvold--who is expected to be on hand at a May 1 invite-only dedication ceremony at the Computer History Museum--is a collector interested in, among other things, historical computers. And as someone with the resources to pay for a difference engine--and the interest--he did so.

The process of making the new difference engine did not turn out as planned, Horton said. Along the way, there were a series of gaffes that led to a much longer construction time than expected.

The most egregious mistake was that one of the companies contracted to create specific elements of the machine put parts of it under the wrong heat treatment, and in the process warped and cracked the cams--there are 14 sets of cams which control the engine's drums.

The problem with that, Horton explained, is that the malformed cams affected the difference engine's handle, which must be cranked to operate the machine. It was almost impossible to turn, he explained.

"It wouldn't have worked," he said. "No way."

The error cost the team six months of building time.

Another problem was that one of the main contracting firms working on the project went into liquidation just before the main construction process began, and that meant Horton and his small team ended up having to make many components and rework badly formed pieces themselves.

The biggest problem the contractor's liquidation presented the team with was that many of the machine's pieces had to be hand-fitted, and hand-filed so that they were in acceptable condition, Horton explained. That meant another four months' delay.

"For Victorian requirements," Horton said, speaking of Babbage's design constraints, "we had to be sure all the finishing (was as perfect) as we could meaningfully get them."

Ultimately, the machine's 248 figure wheels--gears used for computation--did fit properly onto their bearings, Horton said.

"Every one had to be done by hand," he said. "If there was tightness on any of the 248, the friction would have been massive."

It was a frustrating experience, he added, but "then we got the type of fit we wanted...It was better to fit them ourselves than have them be too loose."

Some might find it odd that people today are building machines based on a 19th century design whose creator never managed to bring it to fruition. But Horton said that for Babbage, the problem was financial: He simply didn't have the money to pull it off.

That's why it's so exciting to many that this new machine has come to Mountain View and will stay in the U.S.

Asked what we can learn from the machine, Horton said that it shows how engineering would have been done in Victorian times.

Amazingly, while today's computers can perform billions of calculations in a second, the difference engine could only do one--generally calculating algorithmic, trigonometric and navigational tables--every six seconds. On the other hand, the difference engine trumps today's machines for pure beauty.

So it should have come as no surprise that there was a crowd gathered just for the delivery of the machine. And even though the machine was hours late, the crowd lingered, snapping endless pictures when it finally did arrive--only to have a work crew spend an additional three hours or so simply getting the machine off the delivery truck. It took an additional couple of hours to get the machine into the museum.

But get it in they did, with the help of some clever on-the-ground engineering to get the 9,000-pound machine up a slightly inclined walkway and through and around a rather narrow entry way. (See more photos of the supersize unboxing in our photo gallery here.)

And when, at last, it had been shimmied into place, directly under a pair of specially installed chandeliers, the gathered crowd broke out in applause.

And that was even before anyone got to see the machine itself. All the while, from when it came off the truck, to when it was brought inside, it was under wraps.

But finally, Horton and Shulver began to rip the tape and covering off, and slowly but surely, one of the most beautiful pieces of machinery I've ever seen came into view.

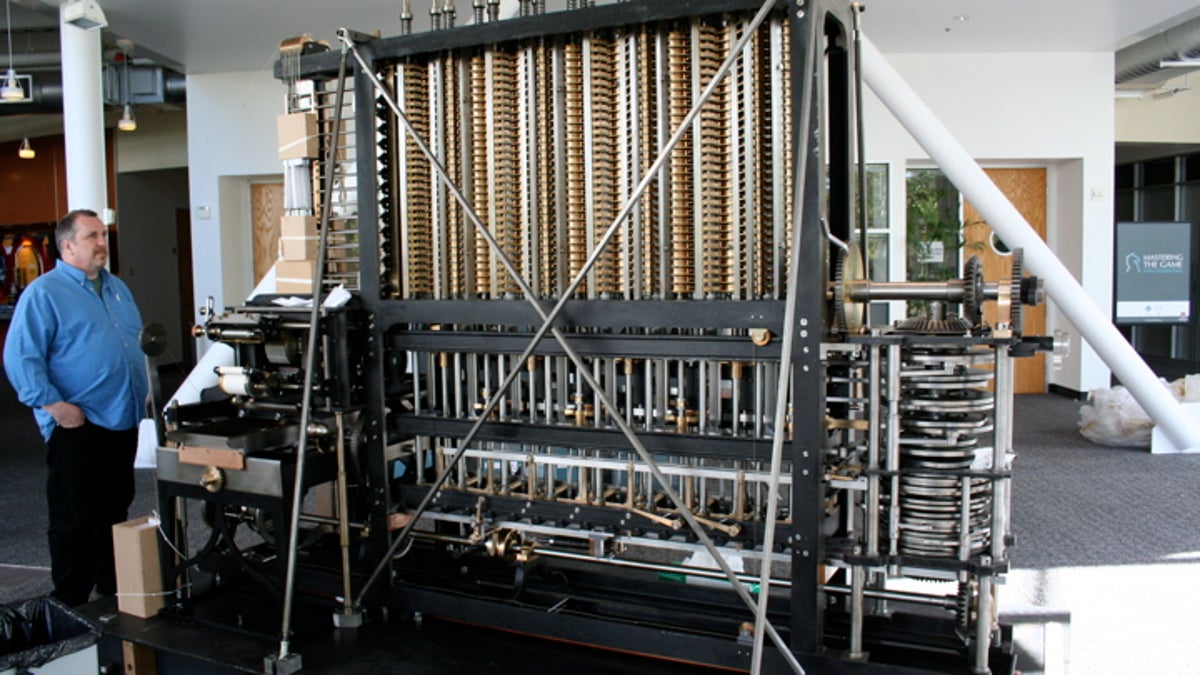

When it did, I beheld a stunning piece of workmanship: 9 feet tall, with 8,000 parts, gleaming in the light and obviously never having been used before. The gears were spotless, the symmetry of all the parts was breathtaking and the obvious thousands and thousands of hours of work that went into it was just one of the best things I've ever seen in person.

It was so new, in fact, that one of the first things Horton did when he finished unpacking it was to wipe oil off many of the gears. And Shulver told me that over the next few days he and others would polish much of the steel so that it would shine like silver.

For Horton, meanwhile, the project is now pretty much over. He expects to be on hand for the May 10 opening, but then he'll have to go back to London and resume working for the museum. And it's unlikely he'll get to build another difference engine.

"I don't think any project...can compare," he said, wistfully. "It is (a once in a lifetime project)."