Brain scan may spot disease in athletes while they're still alive

Until now, a condition called chronic traumatic encephalopathy -- considered to have played a role in the deaths of former NFL players -- could be diagnosed only postmortem.

Chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), a degenerative brain disease thought to play a role in the deaths (which are sometimes suicides) of athletes, soldiers, and others who have suffered concussions and repeated hits to the head, is currently only able to be diagnosed postmortem.

"After a while it gets old and not so fulfilling to take the brain out when [an athlete] is dead," Julian Bailes, a neurosurgeon and director of the Brain Injury Research Institute, told CNN. "At that point there is no solution, no answer."

So a study co-authored by Bailes suggesting that PET scans may be used to diagnose CTE in living patients brings some hope to those at the greatest risk for developing the disease.

The study, published this week in The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and funded in part by the Brain Injury Research Institute, which Bailes co-founded, is small and preliminary at best, but it could be an important step toward developing ways to prevent and treat -- not just identify -- the disease.

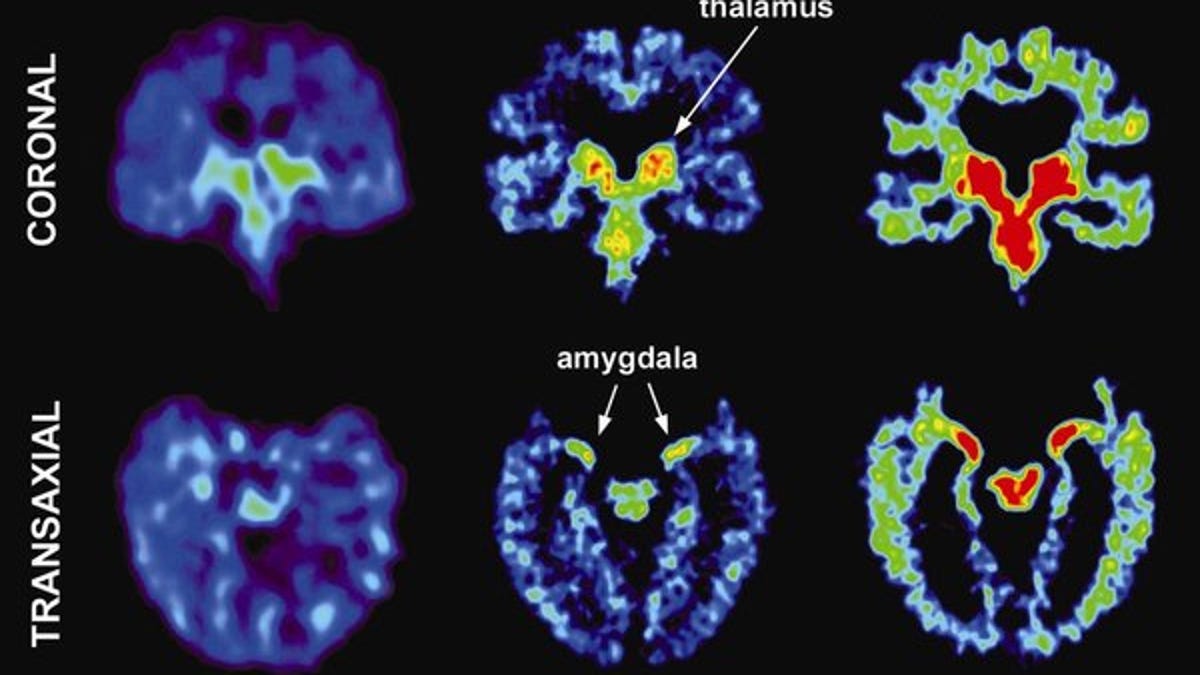

In the study researchers injected FDDNP, a chemical marker designed to bind to deposits of amyloid beta plaques and neurofibrillary tau tangles, which indicate Alzheimer's disease, into five retired NFL players (a linebacker, guard, center, defensive lineman, and quarterback) who were at least 45 years old, had sustained at least one concussion, and who reported mood swings, depression, and cognitive issues.

They were then given PET scans, which were compared to the scans of healthy men with similar body mass, age, education, and family history of dementia.

The NFL players' scans revealed tau protein deposits, and that they in fact presented identically to the pattern of deposits found in the autopsies of people who'd suffered from CTE.

"We found [the tau] in their brains; it lit up," Gary Small, professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behavior at UCLA and lead author of the study, told CNN. "It's different from Alzheimer's. The patterns of the scans are identical to what's seen at autopsy in other people [with CTE]."

The New York Times reports that some researchers are calling into question the accuracy of the dye, not to mention taking issue with the incredibly small sample size of five, but Bailes says that this research is still helping to connect more dots.

Regardless, larger studies, that follow members of the general population over many years, will be required to better understand who is predisposed to the disease and how. And even then, potential treatments -- which are at this point speculative given the disease has only been diagnosed posthumously -- may be years, if not decades, away. As for prevention, avoiding situations that carry the risk of concussion would be career-ending for many in the military and in high-contact professional sports.