Beyond Fitbit: 'Neural dust' puts invisible cyborg tech deep inside you

New, tiny sensors could create superpowerful fitness trackers, move prosthetics forward and lead to treatments for conditions like epilepsy.

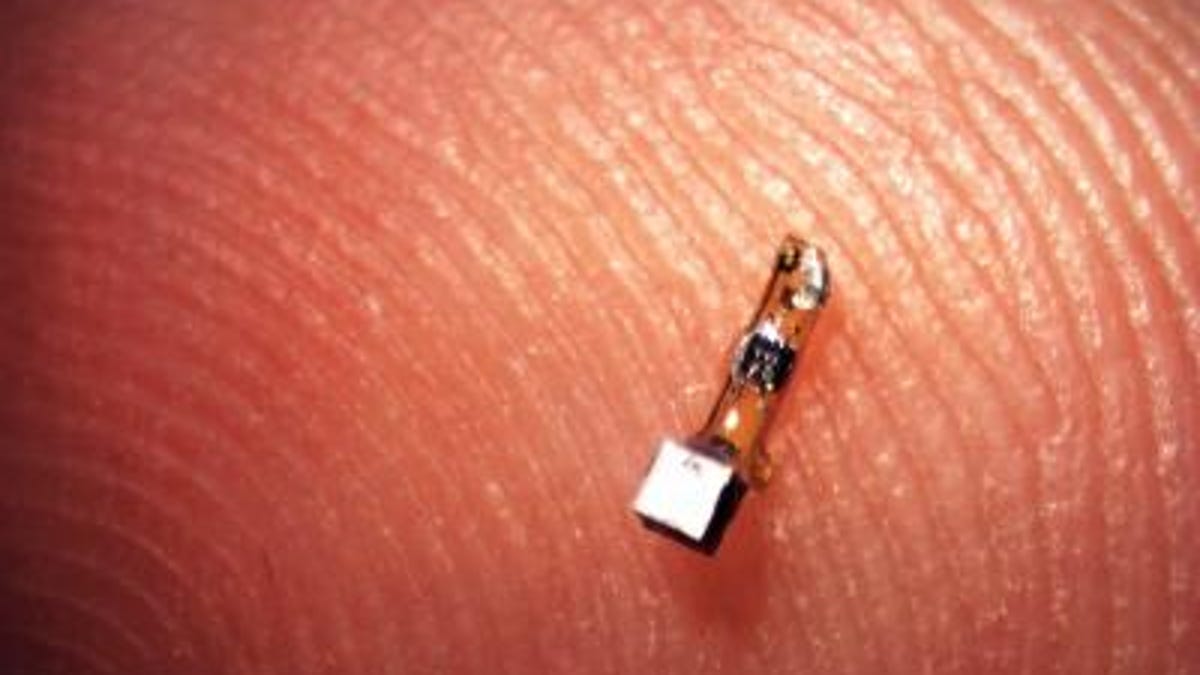

A mote of "neural dust"

Monitoring your heart rate and VO2 max (maximum oxygen volume) with the latest fitness tracker is nifty, but researchers are developing new, tiny tech to keep track of just about any organ, nerve or muscle in real time. If that's not futuristic-cyborg-cool enough for you, the so-called "neural dust" could also be used to stimulate nerves and muscles, ushering in a new era of "electroceutical" treatment for things like epilepsy or inflammation.

Engineers at the University of California, Berkeley, have developed sensors that are about the size of a large grain of sand and use ultrasound to both power the implant and transmit data. Neural-dust implants have successfully been implanted in the muscles and nerves of rats and the researchers hope to create even smaller sensors that could be used in the brain.

"I think the long-term prospects for neural dust are not only within nerves and the brain, but much broader," said Michel Maharbiz, an UC-Berkeley engineering and computer sciences professor of electrical engineering and co-author of a paper on the new technology in Wednesday's issue of the journal Neuron. "Having access to in-body telemetry has never been possible because there has been no way to put something super-tiny super-deep. But now I can take a speck of nothing and park it next to a nerve or organ, your [gastrointestinal] tract or a muscle, and read out the data."

The team is working to build tiny sensors with materials that are compatible with the body and could last for a decade or more without degrading.

"The beauty is that now, the sensors are small enough to have a good application in the peripheral nervous system, for bladder control or appetite suppression, for example," said Berkeley professor, neuroscientist and co-author Jose Carmena. "The technology is not really there yet to get to the 50-micron target size, which we would need for the brain and central nervous system. Once it's clinically proven, however, neural dust will just replace wire electrodes. This time, once you close up the brain, you're done."

Today, most electrodes implanted in the brain to control prosthetics connect to wires that pass through holes in the skull and only last a couple of years. Using even smaller motes of neural dust could allow the wireless sensors to be permanently installed and sealed in the skull, reducing infection and the unwanted movement that can come with electrodes.

"The original goal of the neural dust project was to imagine the next generation of brain-machine interfaces, and to make it a viable clinical technology," neuroscience graduate student Ryan Neely said in a release. "If a paraplegic wants to control a computer or a robotic arm, you would just implant this electrode in the brain and it would last essentially a lifetime."

Sometimes science really is like magic. But there's still more work to do. Human tests are still to come and the team is currently building tiny backpacks for rats to wear that will hold ultrasound transceivers to record data from their implanted neural dust.

Future plans also include developing motes that can detect nonelectrical signals like oxygen and hormone levels.

Finally we are moving beyond "Jetsons" tech. Smart-home developers take note -- someday soon I expect you to be able to take note of my (or my wife's) wirelessly transmitted hormone levels and choose the appropriate mood music and lighting without being told.