1,000 year old music reconstructed from lost musical language

Music that hasn't been heard for 1,000 years has been reconstructed from a Medieval musical notation technique lost for centuries.

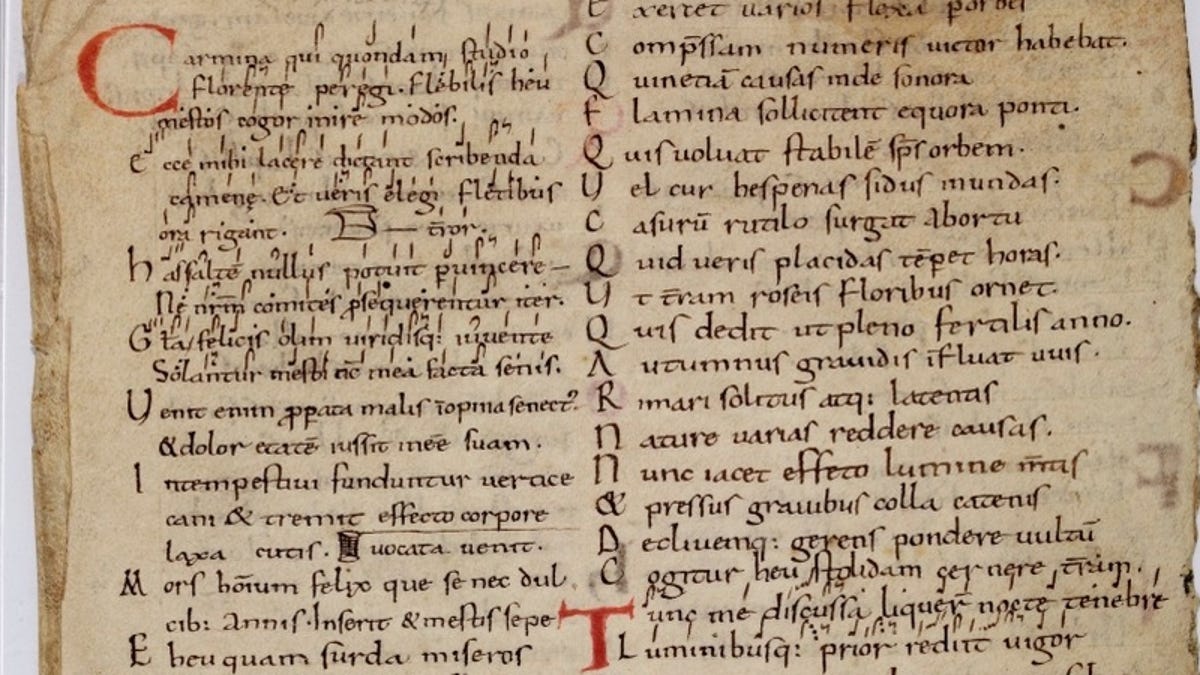

In the Middle Ages, musical notation was a little different to what we have now. In fact, staved notation -- notes written on a staff, or set of horizontal, parallel lines -- wasn't introduced until around the 11th century. Prior to then, the notation, or neumes, was written in a sort of code that sketched out the outline of the music, but relied heavily on aural tradition and prior familiarity with the system.

When staved notation was introduced, these traditions were unneeded and gradually became lost to the sands of time.

Sam Barrett of the University of Cambridge has been working for over two decades to decipher some songs laid out in a manuscript penned sometime in the mid-11th century. Now, that music has been played again for the first time in centuries, or at least as near as possible to the original, in a special performance at The University of Cambridge's Pembroke College Chapel. You can listen to two excerpts below.

Called The Cambridge Songs, it consists of 83 poems in Latin, some annotated with neumes. The section with which Barrett was concerned was lost in 1840 when a German scholar removed an important leaf from the manuscript and returned home to Frankfurt. It remained missing for 140 years, not turning up again until historian Margaret Gibson recognised it in the collection of a Frankfurt library in 1982. It was then returned to Cambridge.

The poems on this retrieved section of the Cambridge songs contained 27 examples of different musical metrical forms based on verses from The Consolation of Philosophy by sixth-century philosopher Boethius. Using the neumes, Barrett slowly and painstakingly pieced together the music.

"After rediscovering the leaf from the Cambridge Songs, what remained was the final leap into sound. Neumes indicate melodic direction and details of vocal delivery without specifying every pitch and this poses a major problem," he explained in a statement.

"The traces of lost song repertoires survive, but not the aural memory that once supported them. We know the contours of the melodies and many details about how they were sung, but not the precise pitches that made up the tunes."

The University of Cambridge's Sam Barrett playing with Ben Bagby and Hanna Marti of Sequentia.

When he was around 80 to 90 percent of the way there, he enlisted the aid of Benjamin Bagby of Sequentia, a band that specialises in medieval music. The pair spent two years testing theories against the practicalities of physically making music, both with voice and instrument, and the options available to an 11th-century musician.

"Ben tries out various possibilities and I react to them -- and vice versa. When I see him working through the options that an 11th century person had, it's genuinely sensational; at times you just think 'that's it!' He brings the human side to the intellectual puzzle I was trying to solve during years of continual frustration," Barrett said.

"There have been times while I've been working on this that I have thought I'm in the 11th century, when the music has been so close it was almost touchable. And it's those moments that make the last 20 years of work so worthwhile."