Quasars and supernovae and huge mirrors, oh my

Northeast of San Diego, storied Palomar Observatory still beckons scientists with its 200-inch telescope. CNET Road Trip 2012 took a look.

PALOMAR MOUNTAIN, Calif.--If you want to talk big scientific breakthroughs, how about quasars and supernovae?

Those are just two of the most important discoveries in the long, very storied history of the Palomar Observatory, a set of telescopes and other astronomical instruments located at the top of this mountain northeast of San Diego. And while the facility no longer holds quite the place in the astronomy community that it once had, for most of the second half of the 20th century, it was the undisputed champion of the world.

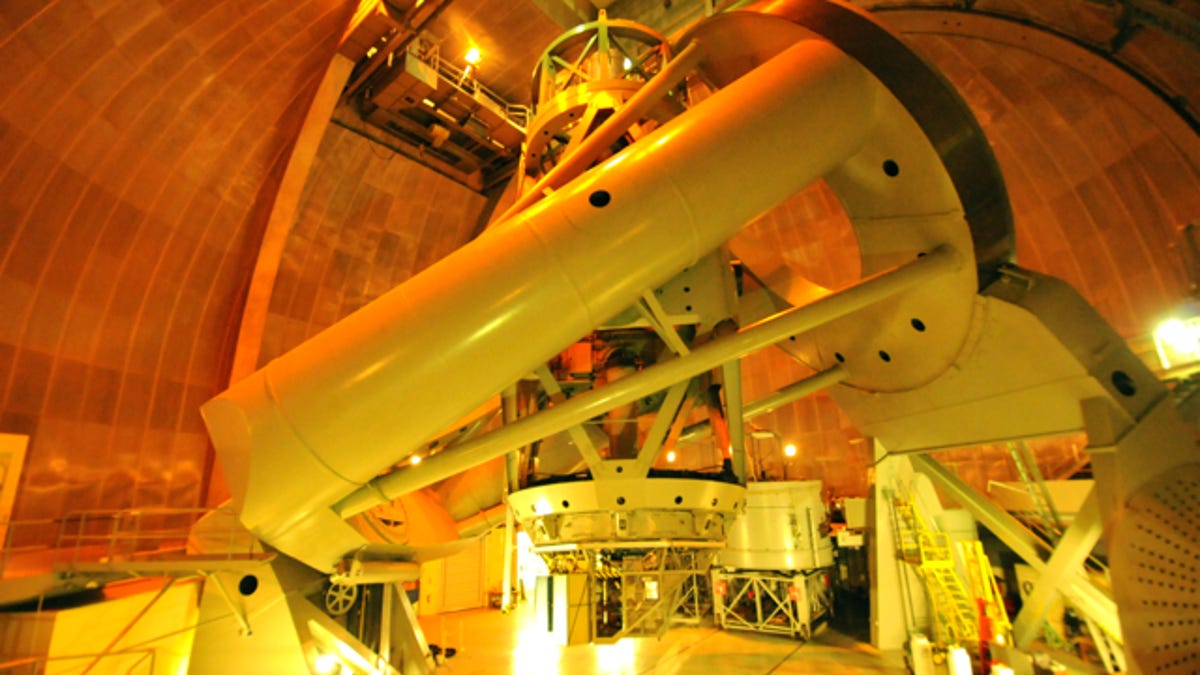

Topping the bill at Palomar is its groundbreaking 200-inch Hale Telescope. Formally deployed in 1948, it was the world's biggest, and most advanced telescope until 1993, when it was knocked off the top of the totem pole by the Keck Observatory in Hawaii.

For George Hale, the creator of the Palomar Observatory, his life's goal was nothing less than building he world's largest telescope -- something he actually did four different times, explained Andy Boden, the deputy director of Caltech Optical Observatories, the California Institute of Technology organization that operates the Palomar Observatory.

But while Hale had been the driving force behind such major facilities as the 100-inch Hooker Telescope at Mount Wilson Observatory in Los Angeles, Boden said that Hale had never quite gotten it "right." That means, Boden explained, that astronomy pioneer Edwin Hubble, who used the Hooker Telescope to discover the general expansion of the universe, had always been annoyed that that instrument had not been able to rotate all the way to the north celestial pole.

At Palomar, however, Hale did get it right, although he didn't live long enough to see his masterpiece completed. But to this day -- the Hale Telescope is still used by scientists about 290 nights a year -- the telescope scans the skies, unhindered by any limits on what it can look at.

200-inch mirror

The heart of the 520-ton Hale Telescope is its mammoth 200-inch mirror, which -- along with its steel holding cell -- weighs 14.5 tons, and took its maker, Corning, 12 years to deliver. The telescope itself, though, was innovative in that it was able to rotate to the north celestial pole, and anywhere else, for that matter, because of its equatorial mount, a giant horseshoe design, that aligns the telescope's tube along the Earth's rotation.

The magic of the giant instrument -- which sits inside a beautiful white dome atop Palomar Mountain that I've come to visit as part of Road Trip 2012 -- is just half a gram of aluminum reflective material on the mirror. Of course, it took engineers designing a system involving 36 pistons underneath the mirror to be able to put enough force on it to keep its shape, given its weight.

As Boden explained it, when the dome cover opens, light come streaming in, shoots down the giant tube, and hits the 200-inch mirror. From there, it is reflected back up the tube to what is known as the Prime Focus Cage. This is where astronomers would sit in the early days of the telescope to do their observations. These days, however, digital optics and computers have made it so that the scientists can do that observing in a data room below the telescope.

The telescope offers another optical configuration, however. A convex secondary mirror is placed "just in front of the prime focus position," the observatory's Web site explained, "reflecting the light back down through a hole in the primary mirror to [what is called] the Cassegrain focus. The Cassegrain focus is somewhat easier to access, and it can accommodate larger instrument packages."

Quasars

The Palomar Observatory has a long list of astronomical highlights that will forever cement its place in the science's history. Of course, not all belong to the 200-inch telescope. In fact, the observatory has two other working telescopes -- an 18-inch instrument that was used to discover supernovae, and a 48-inch telescope that is has been used to conduct what are known as the Palomar Observatory Sky Surveys, a series of scans of the sky that gave astronomers the first real maps of the heavens.

But the big telescope naturally had its triumphs as well. Among them is the discovery of quasars, the "active galactic nucleii," Boden explained. Another major contribution was early work that helped astronomers discover dark energy, though that actual finding was done elsewhere.

These days, however, the telescope is still very much an active part of cutting edge astronomy, Boden said. Although many astronomers prefer to spend time at Keck -- partly because it is bigger and partly because it has less light pollution -- Palomar is still a top-tier facility.

Among the recent "home runs," Boden explained, have been work on the 48-inch telescope on what is known as the Palomar Transient Factory, "a fully-automated, wide-field survey aimed at a systematic exploration of the optical transient sky" in order to look for stellar sources whose brightness is changing. One big result of that was the discovery of the supernova M101, just hours after it exploded. As well, over the last five years, he said, there has been important work done here recently on finding and studying new kinds of hyperluminous supernovae.

Light pollution

When the observatory was first built, there were very few light sources anywhere near Palomar Mountain. These days, however, towns and cities are encroaching from several directions, and the pure darkness of the night sky is a thing of the past, forcing anyone who needs to work in such conditions to go elsewhere, primarily Keck, where there is nothing around for hundreds of miles.

Still, Boden said, the communities near Palomar have been "incredibly cooperative" for 40 years at doing what they can to minimize the light they emit. Some have enacted light ordinances and mandated special lights, and even San Diego has sought the observatory's input on new light regulations.

The upshot is that there is no shortage of scientists seeking to do research at Palomar. Though some may prefer to head to Hawaii or elsewhere, Palomar and its celebrated telescopes are a big part of astronomy's history, and if people like Boden have anything to say about it, its future.