Google tries its own take on customer service

Not surprisingly, the search giant thinks automation and innovation are important. But as CEO Eric Schmidt says, everyone wants to wring a neck when things go wrong.

If you rely on a compelling service that happens to be free, what level of customer support are you entitled to receive?

Google is trying to figure that out. Known for using brilliant engineers, complex algorithms and speedy servers to organize online information in a simple and accessible fashion, Google is learning how to add the human touch to its repertoire as customers look for answers that can't be found on an FAQ.

Not surprisingly, not everyone is happy with the results. Some advertisers have been complaining about Google's Web-page-first approach to customer service issues for years, with the most common gripe that they find it exceedingly difficult to reach a real live human being when they have a problem that isn't answered on a product Web page. More recently, Katie Braband, who reported problems with Google Checkout's handling of transactions at her company, Datto, was just as frustrated by Google's response to her issues as she was the issues themselves. "The only e-mails we've received response to are pre-generated, it's very clear there's no person writing the e-mail," she said in September.

Google is aware that customer service will play a large role in its growth as it offers more paid services, and seems committed to improving services for those kinds of customers over time. "The first thing a CIO is going to say is, 'where is that person and how do I wring their neck?'" said Google CEO Eric Schmidt in an interview earlier this year. Schmidt knows a thing or two about traditional enterprise customer service: he ran corporate software maker Novell before joining Google. And before Novell, he was an executive at Sun Microsystems.

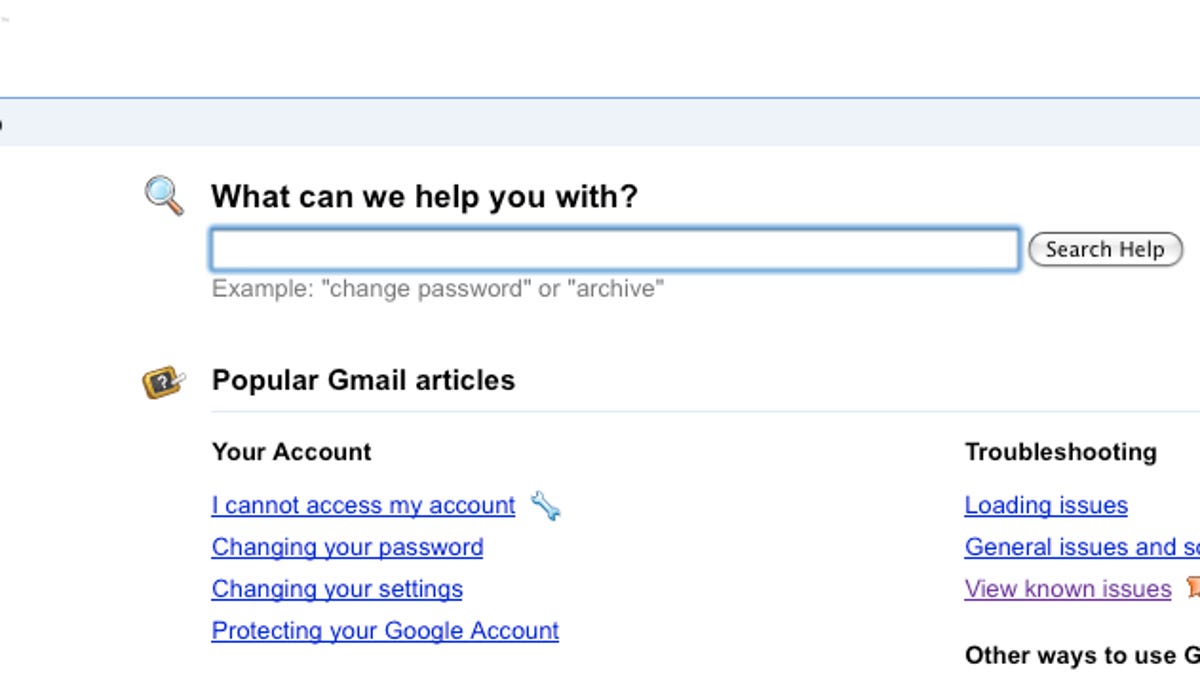

For many users of Google's free services, support is limited to a series of Web pages, FAQs, and user forums. That's not that surprising, since Google can't realistically offer phone support to every Gmail user who can't figure out the conversation-based design.

But as Google continues to push forward with free advertising-supported services that people and small businesses increasingly rely on in their personal and professional lives, the company appears to be banking on its ability to train those users to expect a healthy dose of relatively low-cost support. Web pages with hints, troubleshooting tips, and discussion forums are the first level of support across virtually all of Google's products and are pretty much the end of the line for those who do not pay to use products or services. That's not unusual in technology; even businesses that charge customers for their products have moved in that direction in a bid to cut support costs.

When it comes to Google's main profit engine--the AdWords search keyword ads--there are two basic kinds of customer service, said Deanna Yick, a Google representative. High-roller customers enjoy access to a personal sales team they can reach out and call, but almost everyone else relies on Web-based resources like the AdWords Help Center.

For a while, Google also offered phone support to a proportion of those advertisers without sales team connections. However, it recently reduced the amount of phone support it provides for those not supported by the sales team, leaving e-mail as the sole contact method for a larger segment (Google won't say exactly how many) of its most important customers.

"AdWords is an effective, self-service online advertising platform for advertisers of all sizes worldwide," Google said in a statement regarding the reduction in phone support. "Some clients work with our sales teams, while others prefer to manage their accounts independently. We also provide email and phone support to some advertisers, and have worked hard to build out a robust set of online resources (such as the AdWords Help Center, AdWords Learning Center and user forums) to help advertisers find the answers to their questions around the clock wherever they might be located."

Is this an issue? Google argues that in many cases e-mail and Web support can be faster than sitting on hold waiting for the next customer service representative to answer your call in the order in which it was received. The company can track the most common queries and therefore answer the most commonly asked questions on the Web much more quickly than a telephone-based system would allow, while also developing fixes for commonly reported problems as to cut down on the need for support in the first place.

But on the Google Apps side of the world, the company knows it doesn't have the luxury of pulling back on phone support with its most important customers, said Matthew Glotzbach, director of product management for Google Enterprise.

Here, as well, Google tries to encourage its users to solve their issues through forums and troubleshooting pages. It turns to the solution Google employs for just about everything--an algorithm--to get the most relevant information regarding support issues on those pages and before the people who need detailed answers, and fast.

But Google Apps Premium users--who pay $50 a year per user--can also talk to live Google support personnel anytime day or night when they encounter issues. Years of phone-based IT support has trained system administrators and IT executives to expect the human touch when it comes to advanced support, Glotzbach said, echoing Schmidt's comments last month.

Glotzbach--like any true Googler--believes there are efficiencies just waiting to be discovered that could be greatly improve the customer support experience for both Google and its customers.

"I think this is a fascinating technology and innovation challenge that's properly underappreciated as such," Glotzbach said. "When people think of support, they think of large call centers. But underneath that there is a massive opportunity to innovate." Left unmentioned were the cost savings that accompany automated support.

With innovation comes friction, however, as new ways of thinking about old problems grate on the status quo.

Google is pushing into a whole host of businesses in which it is a newcomer, such as Google Apps, Google Voice, and now Google Maps Navigation. In many cases, those products are free, which reduces expectations for premium support (usually). But those products compete against paid products and services that do provide some level of support.

As more and more people rely on these free services--and Google crowds out competitors who can't compete with free--support issues will grow. Even products that "just work" fail from time to time, and those failures present opportunities for companies to build loyalty if they handle the support encounter the right way, and resentment if they don't.

Can Google train those customers to expect a passive Web-based support experience? Or will Google's free strategy evolve into two groups, those willing to tolerate passive support for free, and those willing to pay a little extra for more service?

Either way, managing the customer experience has been a relatively easy task for Google up until now; basic search requires little customer support. It's about to get a lot more difficult.